Last week, my friend working in the field of infrastructure management gave me an overview of Infrastructure as Code (IaC).

He came across a tool called Terraform which can automate the deployment and management of cloud resources. Hence, together, we researched on ways to build a simple demo in order to demonstrate how Terraform can help in the cloud infrastructure management.

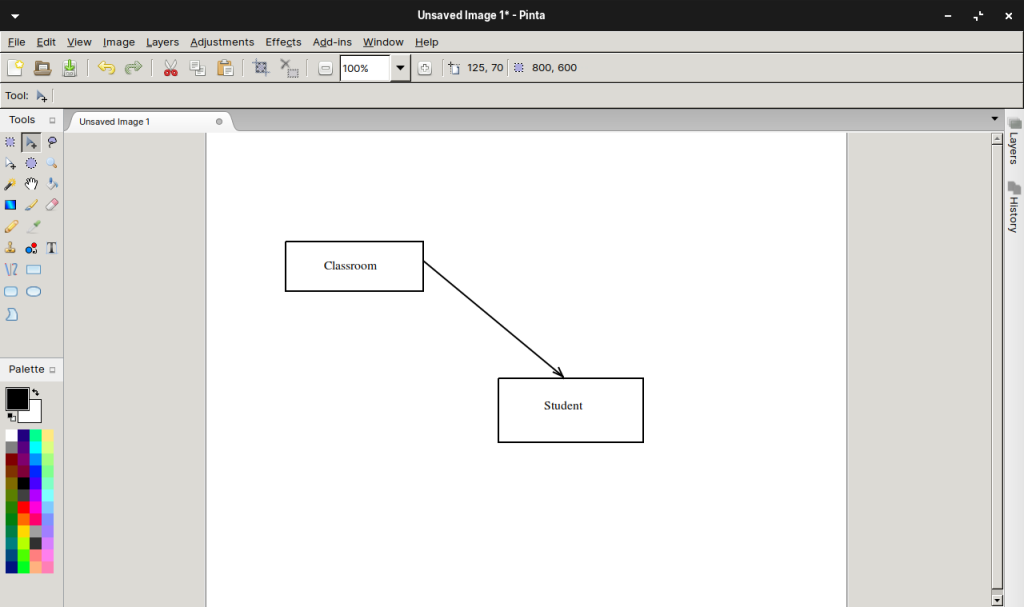

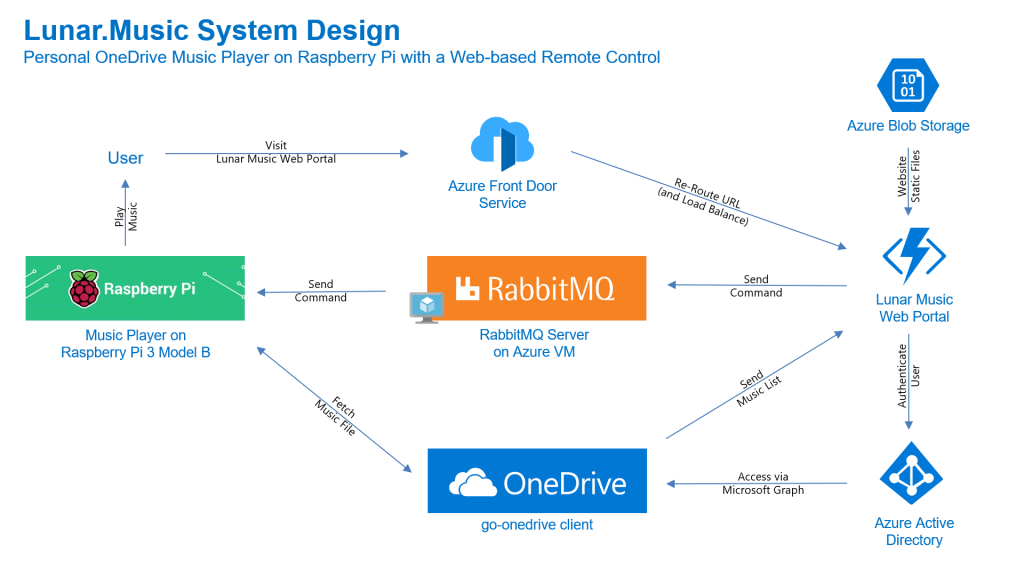

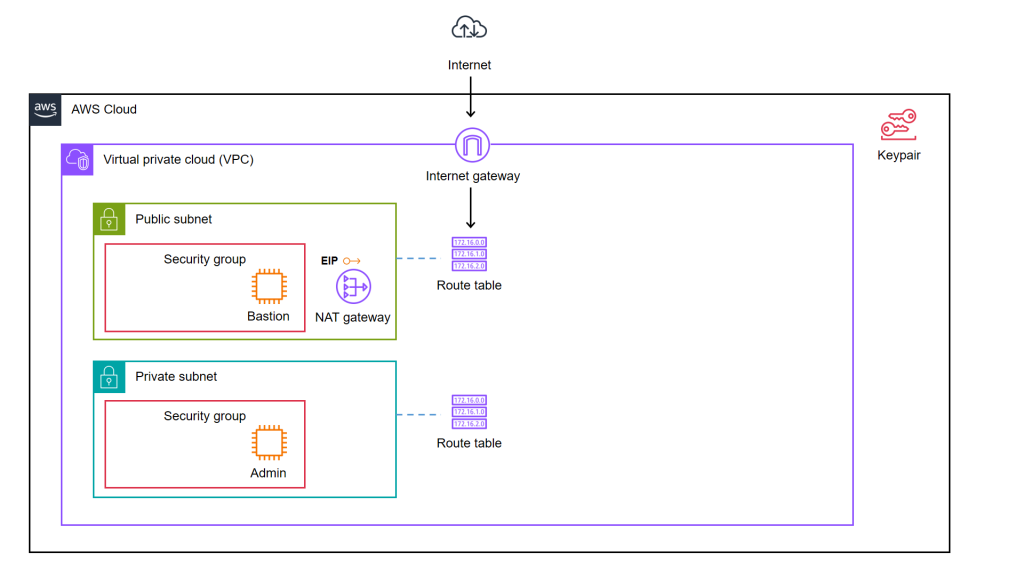

We decided to start from a simple AWS cloud architecture as demonstrated below.

As illustrated in the diagram, we have a bastion server and an admin server.

A bastion server, aka a jump host, is a server that sits between internet network of a company and the external network, such as the Internet. It is to provide an additional layer of security by limiting the number of entry points to the internet network and allowing for strict access controls and monitoring.

An admin server, on the other hand, is a server used by system admins to manage the cloud resources. Hence the admin server typically includes tools for managing cloud resources, monitoring system performance, deploying apps, and configuring security settings. It’s generally recommended to place an admin server in a private subnet to enhance security and reduce the attack surface of our cloud infrastructure.

In combination, the two servers help to ensure that the cloud infrastructure is secure, well-managed, and highly available.

Show Me the Code!

The complete source code of this project can be found at https://github.com/goh-chunlin/terraform-bastion-and-admin-servers-on-aws.

Infrastructure as Code (IaC)

As we can see in the architecture diagram above, the cloud resources are all available on AWS. We can set them up by creating the resources one by one through the AWS Console. However, doing it manually is not efficient and it is also not easy to be repeatedly done. In fact, there will be other problems arising from doing it with AWS Console manually.

- Manual cloud resource setup leads to higher possibility of human errors and it takes longer time relatively;

- Difficult to identify cloud resource in use;

- Difficult to track modifications in infrastructure;

- Burden on infrastructure setup and configuration;

- Redundant work is inevitable for various development environments;

- Restriction is how only the infrastructure PIC can setup the infrastructure.

A concept known as IaC is thus introduced to solve these problems.

IaC is a way to manage our infrastructure through code in configuration files instead of through manual processes. It is thus a key DevOps practice and a component of continuous delivery.

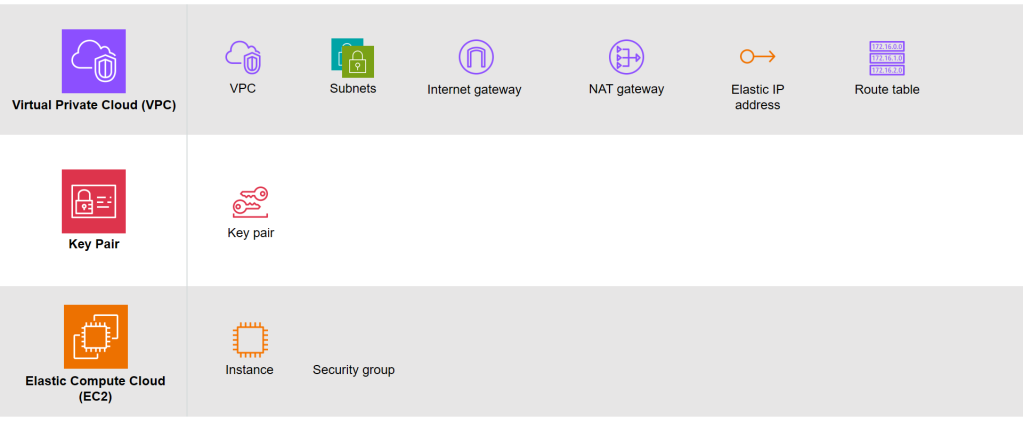

Based on the architecture diagram, the services and resources necessary for configuring with IaC can be categorised into three parts, i.e. Virtual Private Cloud (VPC), Key Pair, and Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2).

There are currently many IaC tools available. The tools are categorised into two major groups, i.e. those using declarative language and those using imperative language. Terraform is one of them and it is using Hashicorp Configuration Language (HCL), a declarative language.

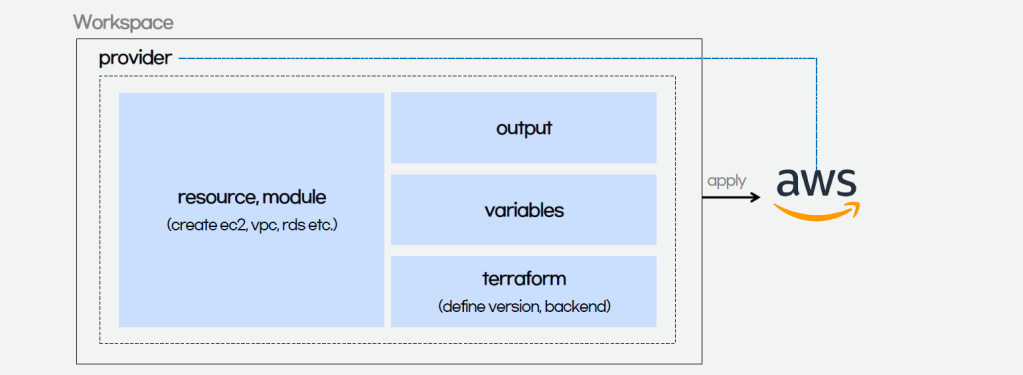

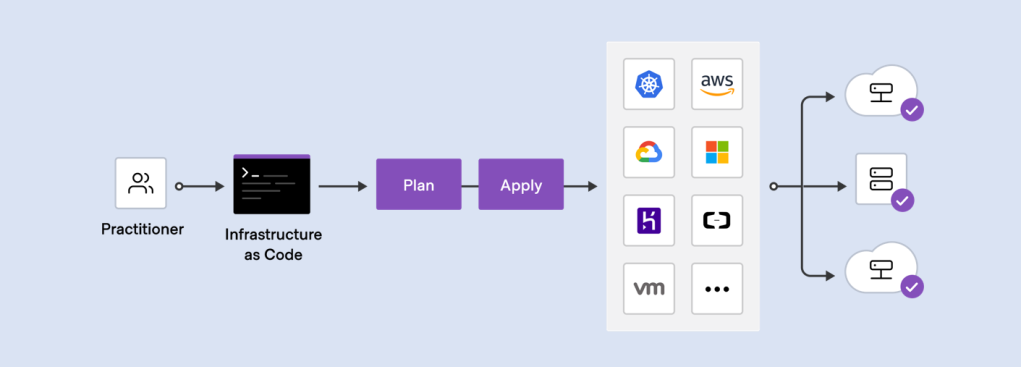

The workflow for infrastructure provisioning using Terraform can be summarised as shown in the following diagram.

We first write the HCL code. Then Terraform will verify the status of the code and apply it to the infrastructure if there is no issue in verification. Since Terraform is using a declarative language, it will do the identification of resources itself without the need of us to manually specify the dependency of resources, sometimes.

After command apply is executed successfully, we can check the applied infrastructure list through the command terraform state list. We can also check records of output variable we defined through the command terraform output.

When the command terraform apply is executed, a status information file called terraform.tfstate will be automatically created.

After understanding the basic process of Terraform, we proceed to write the HCL for different modules of the infrastructure.

Terraform

The components of a Terraform code written with the HCL are as follows.

In Terraform, there are three files, i.e. main.tf, variables.tf, and outputs.tf recommended to have for a minimal module, even if they’re empty. The file main.tf should be the primary entry point. The other two files, variables.tf and outputs.tf, should contain the declarations for variables and outputs, respectively.

For variables, we have vars.tf file which defines the necessary variables and terraform.tfvars file which allocated value to the defined variables.

In the diagram above, we also see that there is a terraform block. It is to declare status info, version info, action, etc. of Terraform. For example, we use the following HCL code to set the Terraform version to use and also specify the location for storing the status info file generated by Terraform.

terraform {

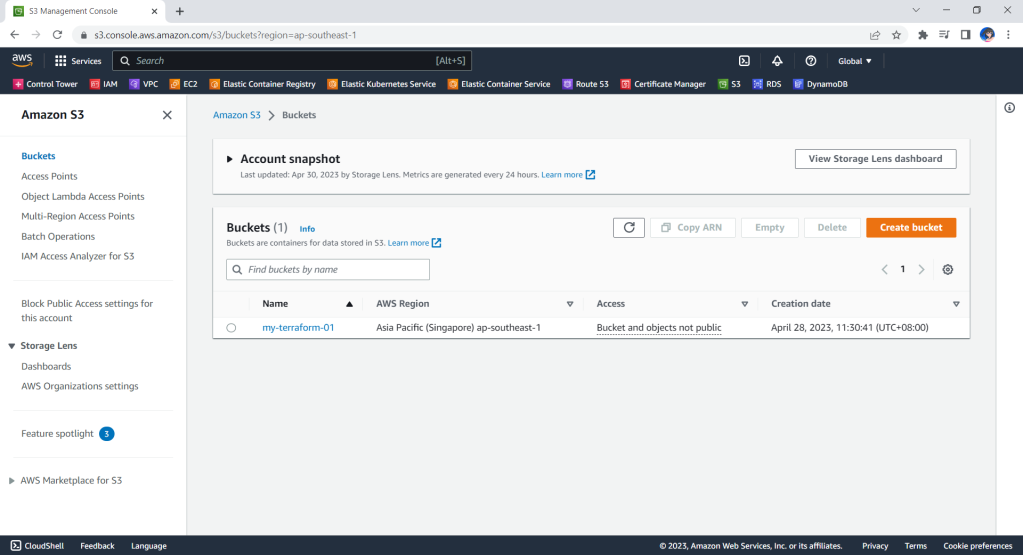

backend "s3" {

bucket = "my-terraform-01"

key = "test/terraform.tfstate"

region = "ap-southeast-1"

}

required_version = ">=1.1.3"

}

Terraform uses a state file to map real world resources to our configuration, keep track of metadata, and to improve performance for large infrastructures. The state is stored by default in a file named “terraform.tfstate”.

The reason why we keep our terraform.tfstat file on the cloud, i.e. the S3 bucket, is because state is a necessary requirement for Terraform to function and thus we must make sure that it is stored in a centralised repo which cannot be easily deleted. Doing this also good for everyone in the team because they will be working with the same state so that operations will be applied to the same remote objects.

Finally, we have a provider block which declares cloud environment or provider to be created with Terraform, as shown below. Here, we will be creating our resources on AWS Singapore region.

provider "aws" {

region = "ap-southeast-1"

}

Module 1: VPC

Firstly, in Terraform, we will have a VPC module created with resources listed below.

1.1 VPC

resource "aws_vpc" "my_simple_vpc" {

cidr_block = "10.2.0.0/16"

tags = {

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-my-vpc",

}

}

The resource_prefix is a string to make sure all the resources created with the Terraform getting the same prefix. If your organisation has different naming rules, then feel free to change the format accordingly.

1.2 Subnets

The public subnet for the bastion server is defined as follows. The private IP of the bastion server will be in the format of 10.2.10.X. We also set the map_public_ip_on_launch to true so that instances launched into the subnet should be assigned a public IP address.

resource "aws_subnet" "public" {

count = 1

vpc_id = aws_vpc.my_simple_vpc.id

availability_zone = data.aws_availability_zones.available.names[count.index]

cidr_block = "10.2.1${count.index}.0/24"

map_public_ip_on_launch = true

tags = tomap({

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-public-subnet${count.index + 1}",

})

}

The private subnet for the bastion server is defined as follows. The admin server will then have a private IP with the format of 10.2.20.X.

resource "aws_subnet" "private" {

count = 1

vpc_id = aws_vpc.my_simple_vpc.id

availability_zone = data.aws_availability_zones.available.names[count.index]

cidr_block = "10.2.2${count.index}.0/24"

map_public_ip_on_launch = false

tags = tomap({

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-private-subnet${count.index + 1}",

})

}

The aws_availability_zones data source is part of the AWS provider and retrieves a list of availability zones based on the arguments supplied. Here, we make the public subnet and private subnet to be in the same first availability zones.

1.3 Internet Gateway

Normally, if we create an internet gateway via AWS console, for example, we will sometimes forget to associate it with the VPC. With Terraform, we can do the association in the code and thus reduce the chance of setting up the internet gateway wrongly.

resource "aws_internet_gateway" "igw" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.my_simple_vpc.id

tags = {

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-igw"

}

}

1.4 NAT Gateway

Even though Terraform is a declarative language, i.e. a language describing an intended goal rather than the steps to reach that goal, we can use the depends_on meta-argument to handle hidden resource or module dependencies that Terraform cannot automatically infer.

resource "aws_nat_gateway" "nat_gateway" {

allocation_id = aws_eip.nat.id

subnet_id = element(aws_subnet.public.*.id, 0)

depends_on = [aws_internet_gateway.igw]

tags = {

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-nat-gw"

}

}

1.5 Elastic IP (EIP)

If you have noticed, in the NAT gateway definition above, we have assigned a public IP to it using EIP. Since Terraform is declarative, the ordering of blocks is generally not significant. So we can define the EIP after the NAT gateway.

resource "aws_eip" "nat" {

vpc = true

depends_on = [aws_internet_gateway.igw]

tags = {

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-NAT"

}

}

1.6 Route Tables

Finally, we just need to link the resources above with both public and private route tables, as defined below.

resource "aws_route_table" "public_route" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.my_simple_vpc.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

gateway_id = aws_internet_gateway.igw.id

}

tags = {

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-public-route"

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "public_route" {

count = 1

subnet_id = aws_subnet.public.*.id[count.index]

route_table_id = aws_route_table.public_route.id

}

resource "aws_route_table" "private_route" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.my_simple_vpc.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

nat_gateway_id = aws_nat_gateway.nat_gateway.id

}

tags = {

Name = "${var.resource_prefix}-private-route",

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "private_route" {

count = 1

subnet_id = aws_subnet.private.*.id[count.index]

route_table_id = aws_route_table.private_route.id

}

That’s all we need to do the setup the VPC on AWS as illustrated in the diagram.

MODULE 2: Key pair

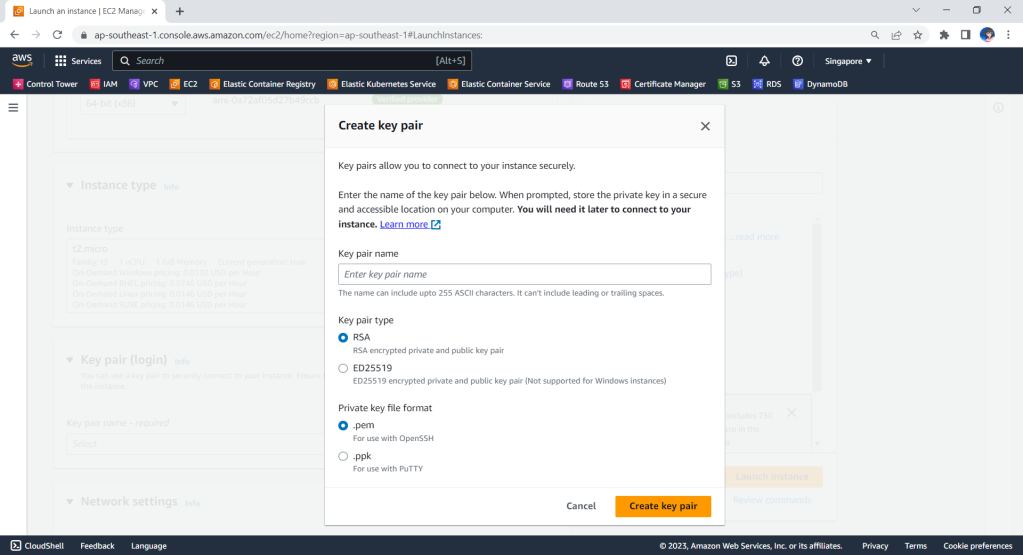

Before we move on the create the two instances, we will need to define a key pair. A key pair is a set of security credentials that we use to prove our identity when connecting to an EC2 instance. Hence, we need to ensure that we have access to the selected key pair before we launch the instances.

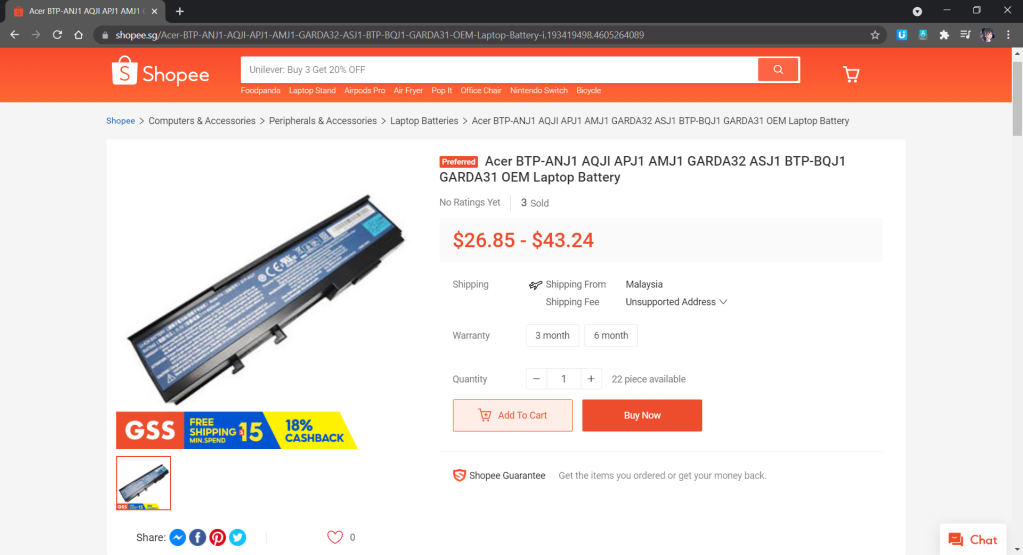

If we are doing this on the AWS Console, we will be seeing this part on the console as shown below.

So, we can use the same info to define the key pair.

resource "tls_private_key" "instance_key" {

algorithm = "RSA"

}

resource "aws_key_pair" "generated_key" {

key_name = var.keypair_name

public_key = tls_private_key.instance_key.public_key_openssh

depends_on = [

tls_private_key.instance_key

]

}

resource "local_file" "key" {

content = tls_private_key.instance_key.private_key_pem

filename = "${var.keypair_name}.pem"

file_permission ="0400"

depends_on = [

tls_private_key.instance_key

]

}

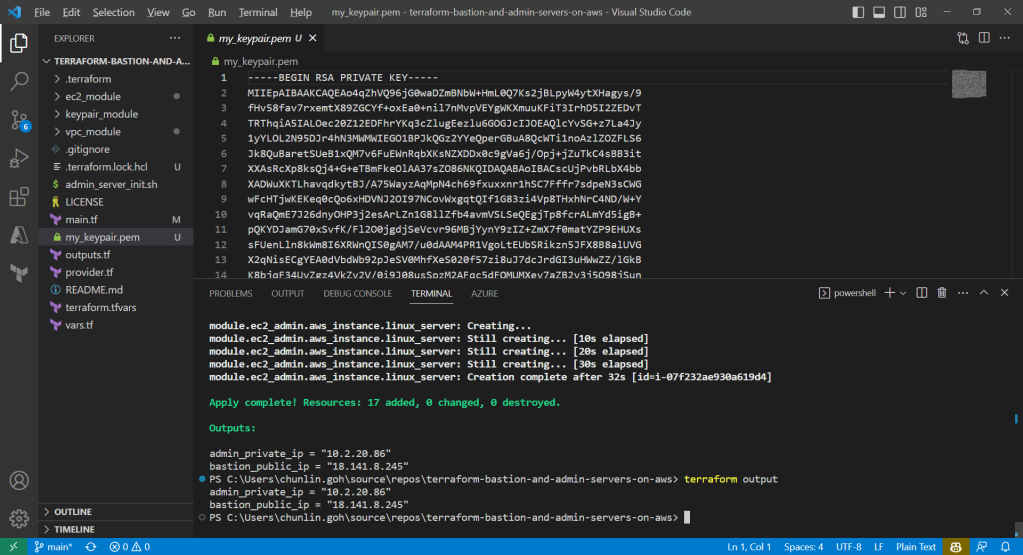

The tls_private_key is to create a PEM (and OpenSSH) formatted private key. This is not a recommended way for production because it will generate the private key file and keep it unencrypted in the directory where we run the Terraform commands. Instead, we should generate the private key file outside of Terraform and distribute it securely to the system where Terraform will be run.

MODULE 3: EC2

Once we have the key pair, we can finally move on to define how the bastion and admin servers can be created. We can define a module for the servers as follows.

resource "aws_instance" "linux_server" {

ami = var.ami

instance_type = var.instance_type

subnet_id = var.subnet_id

associate_public_ip_address = var.is_in_public_subnet

key_name = var.key_name

vpc_security_group_ids = [ aws_security_group.linux_server_security_group.id ]

tags = {

Name = var.server_name

}

user_data = var.user_data

}

resource "aws_security_group" "linux_server_security_group" {

name = var.security_group.name

description = var.security_group.description

vpc_id = var.vpc_id

ingress {

description = "SSH inbound"

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

description = "Allow All egress rule"

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

tags = {

Name = var.security_group.name

}

}

By default, AWS creates an ALLOW ALL egress rule when creating a new security group inside of a VPC. However, Terraform will remove this default rule, and require us to specifically re-create it if we desire that rule. Hence that is why we need to include the protocol=”-1″ egress block above.

The output.tf of EC2 instance module is defined as follows.

output "instance_public_ip" {

description = "Public IP address of the EC2 instance."

value = aws_instance.linux_server.public_ip

}

output "instance_private_ip" {

description = "Private IP address of the EC2 instance in the VPC."

value = aws_instance.linux_server.private_ip

}

With this definition, once the Terraform workflow is completed, the public IP of our bastion server and the private IP of our admin server will be displayed. We can then easily use these two IPs to connect to the servers.

Main Configuration

With all the above modules, we can finally define our AWS infrastructure using the following main.tf.

module "vpc" {

source = "./vpc_module"

resource_prefix = var.resource_prefix

}

module "keypair" {

source = "./keypair_module"

keypair_name = "my_keypair"

}

module "ec2_bastion" {

source = "./ec2_module"

ami = "ami-062550af7b9fa7d05" # Ubuntu 20.04 LTS (HVM), SSD Volume Type

instance_type = "t2.micro"

server_name = "bastion_server"

subnet_id = module.vpc.public_subnet_ids[0]

is_in_public_subnet = true

key_name = module.keypair.key_name

security_group = {

name = "bastion_sg"

description = "This firewall allows SSH"

}

vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc_id

}

module "ec2_admin" {

source = "./ec2_module"

ami = "ami-062550af7b9fa7d05" # Ubuntu 20.04 LTS (HVM), SSD Volume Type

instance_type = "t2.micro"

server_name = "admin_server"

subnet_id = module.vpc.private_subnet_ids[0]

is_in_public_subnet = false

key_name = module.keypair.key_name

security_group = {

name = "admin_sg"

description = "This firewall allows SSH"

}

user_data = "${file("admin_server_init.sh")}"

vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc_id

depends_on = [module.vpc.aws_route_table_association]

}

Here, we will pre-install the AWS Command Line Interface (AWS CLI) in the admin server. Hence, we have the following script in the admin_server_init.sh file. The script will be run when the admin server is launched.

#!/bin/bash sudo apt-get update sudo apt-get install -y awscli

However, since the script above will be downloading AWS CLI from the Internet, we need to make sure that the routing from private network to the Internet via the NAT gateway is already done. Instead of using the depends_on meta-argument directly on the module, which will have side effect, we choose to use a recommended way, i.e. expression references.

Expression references let Terraform understand which value the reference derives from and avoid planning changes if that particular value hasn’t changed, even if other parts of the upstream object have planned changes.

Thus, I made the change accordingly with expression references. In the change, I forced the description of security group which the admin server depends on to use the the private route table association ID returned from the VPC module. Doing so will make sure that the admin server is created only after the private route table is setup properly.

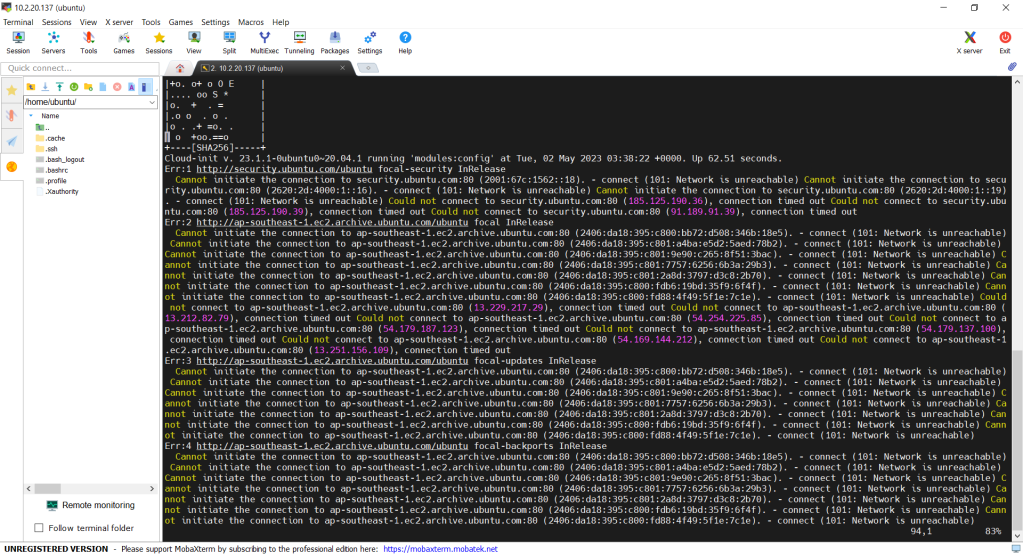

If we don’t force the admin_server to be created after the private route table is completed, the script may fail and we can find the error logs at /var/log/cloud-init-output.log on the admin server. In addition, please remember that even though terraform apply runs just fine without any error, it does not mean user_data script is run successfully without any error as well. This is because Terraform knows nothing about the status of user_data script.

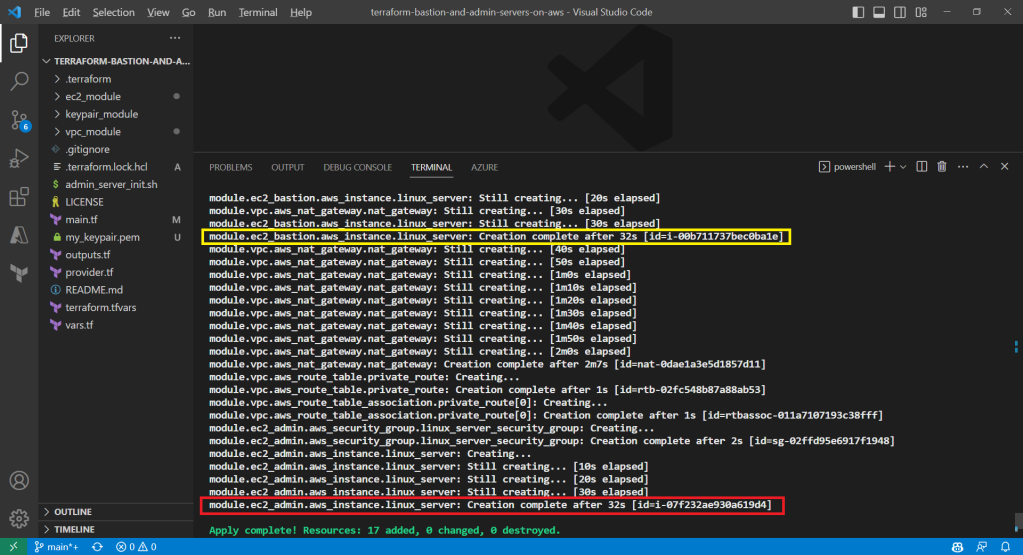

Demo

With the Terraform files ready, now we can move on to go through the Terraform workflow using the commands.

Before we begin, besides installing Terraform, since we will deploy the infrastructure on AWS, we also shall configure the AWS CLI using the following command on the machine where we will run the Terraform commands.

aws configure

Once it is done then only we can move on to the following steps.

Firstly, we need to download plug-in necessary for the defined provider, backend, etc.

After it is successful, there will be a message saying “Terraform has been successfully initialized!” A hidden .terraform directory, which Terraform uses to manage cached provider plugins and modules, will be automatically created.

Only after initialisation is completed, we can execute other commands, like terraform plan.

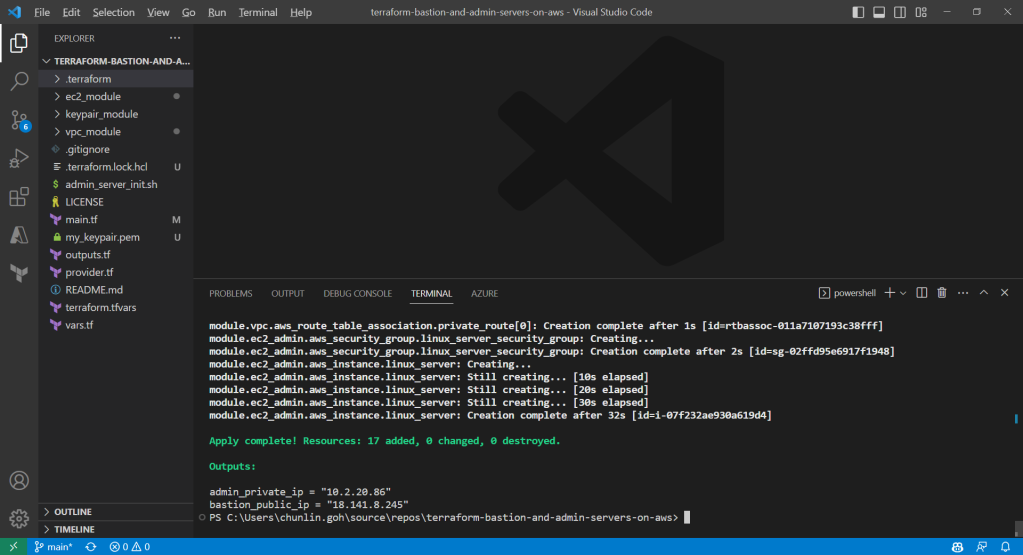

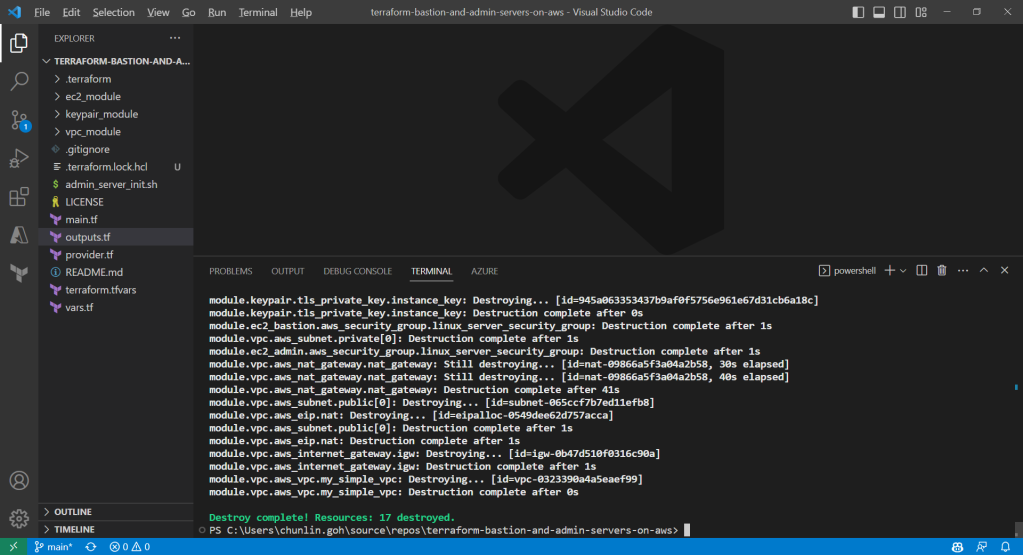

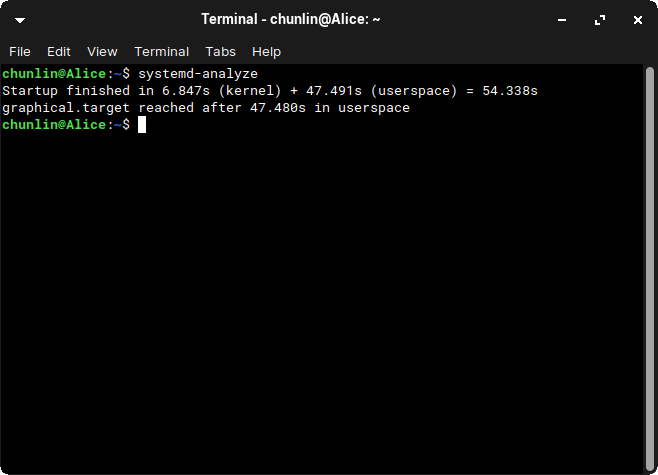

After running the command terraform plan, as shown in the screenshot above, we know that there are in total 17 resources to be added and two outputs, i.e. the two IPs of the two servers, will be generated.

We can also run the command terraform output to get the two IPs. Meanwhile, we can also find the my_keypair.pem file which is generated by the tls_private_key we defined earlier.

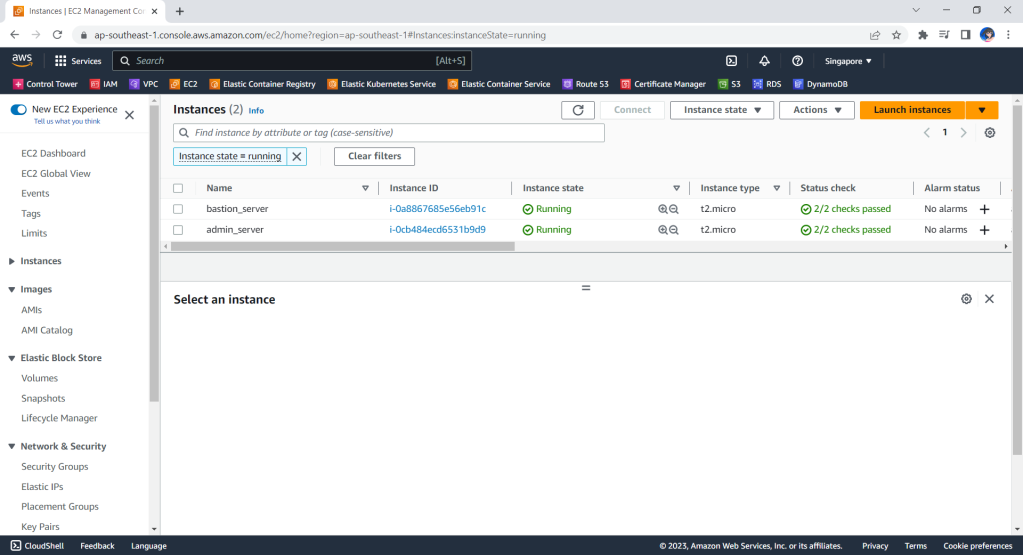

Now, if we check the resources, such as the two EC2 instances, on AWS Console, we should see they are all there up and running.

Now, let’s see if we can access the admin server via the bastion server using the private key. In fact, there is no problem to access and we can also realise that the AWS CLI is already installed properly, as shown in the screenshot below.

Deleting the Cloud Resources

To delete what we have just setup using the Terraform code, we simply run the command terraform destroy. The complete deletion of the cloud resources is done within 3 minutes. This is definitely way more efficient than doing it manually on AWS Console.

Conclusion

That is all for what I had researched on with my friend.

If you are interested, feel free to checkout our Terraform source code at https://github.com/goh-chunlin/terraform-bastion-and-admin-servers-on-aws.