Recently, my team is working on packing our UWP class library as a NuGet package. It turns out that it’s not that straight-forward, because even though there is a documentation from Microsoft, it is for Windows Runtime Component. So, the question on StackOverflow remains unsolved.

I thus decided to document down the steps on how I approach this problem to help the developers out there who are facing the same issue.

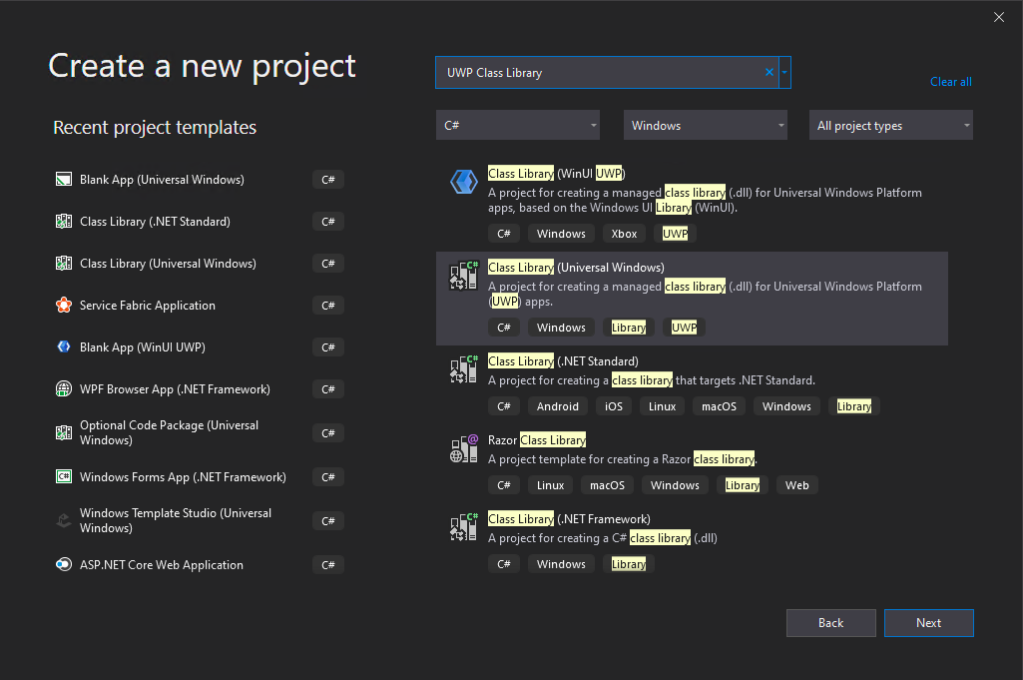

Step 1: Setup the UWP Class Library Project

In this post, the new project we create is called “RedButton” which is meant to provide red button in different style. Yup, it’s important to make our demo as simple as possible so that we can focus on the key thing, i.e. generating the NuGet package.

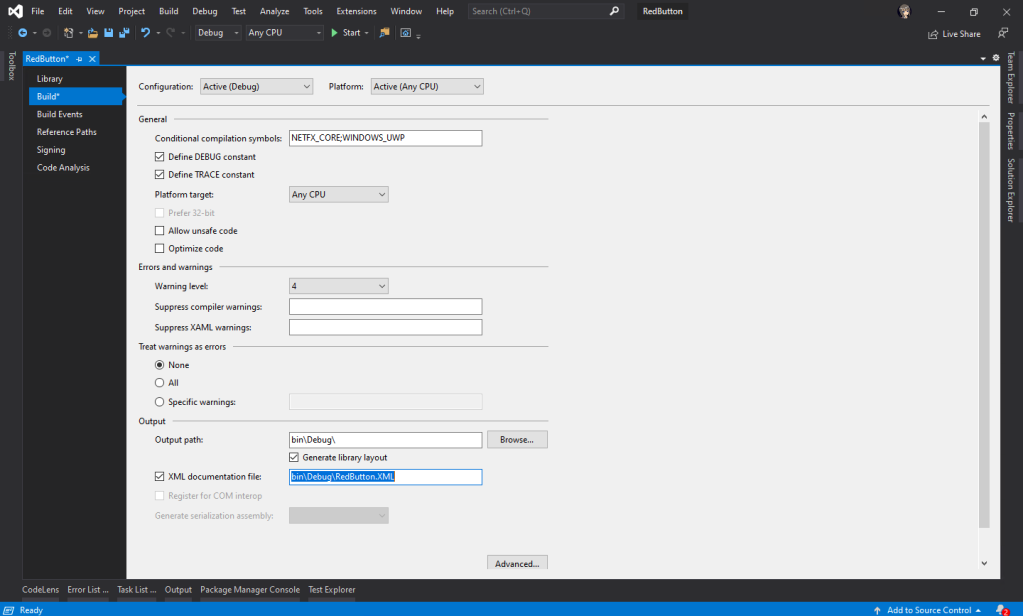

Before we proceed with the new project, we need to configure the project Build properties, as shown in the following screenshot, to enable the XML Documentation file. This will make a XML file generated in the output folder which we need to use later.

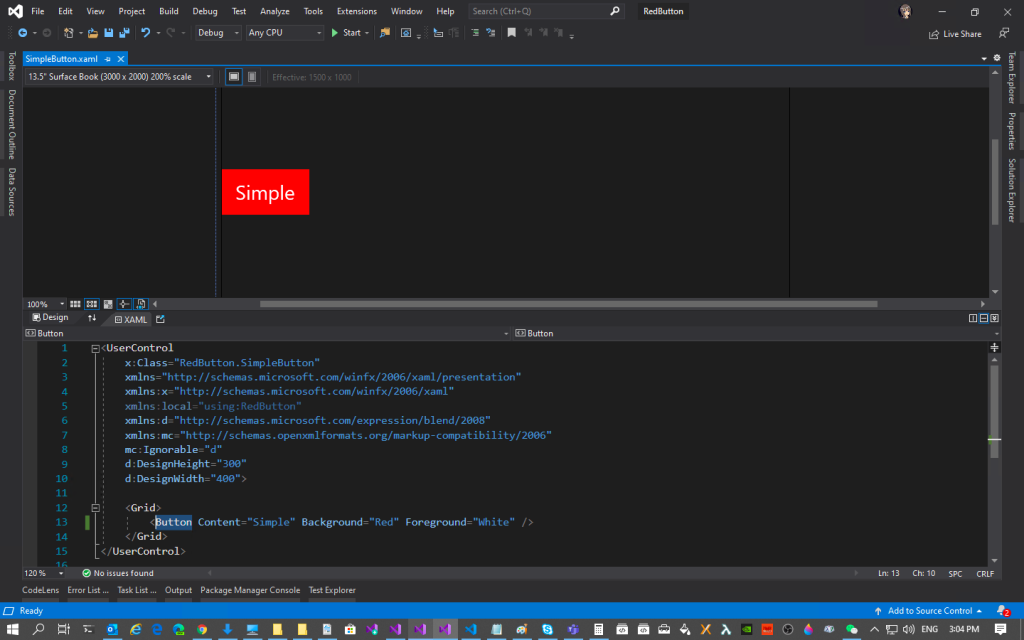

Now, we can proceed to add a new user control, called SimpleButton.xaml.

So this marks the end of the steps where we create an UWP user control where we need to package it with NuGet.

Step 2: Install NuGet.exe

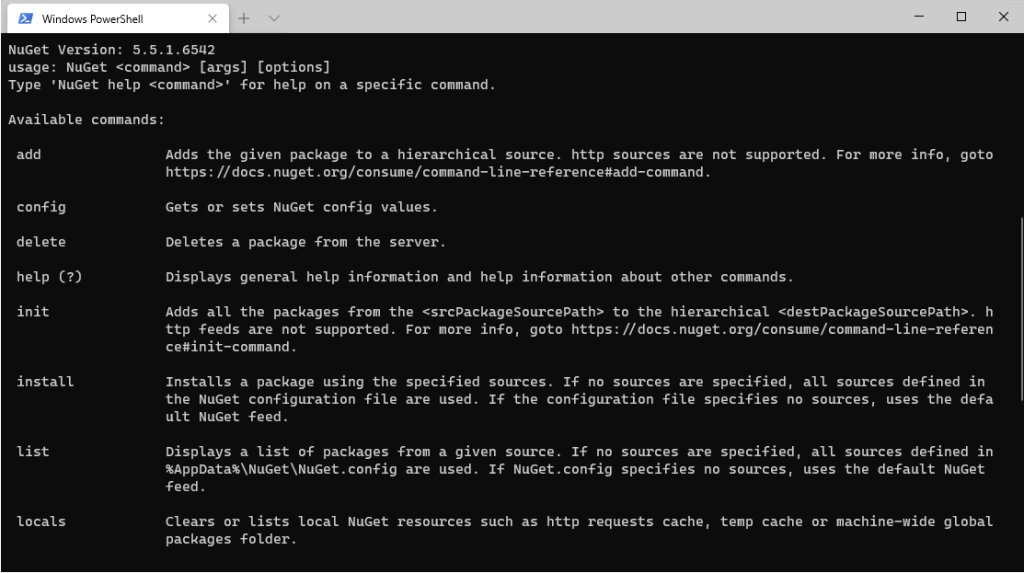

Before we proceed, please make sure we have nuget installed. To verify that, just run the following command in the PowerShell.

> nuget

If it is installed, it will show something as follows.

If it is not installed, please download the latest recommended nuget.exe from the NuGet website. After that, add the path the the folder containing the nuget.exe file in the PATH environment variable.

Step 3: Setup NuSpec

In order to package our class library with NuGet, we need a manifest file called NuSpec. It is a manifest containing the package metadata which provides information to be shown on NuGet and helps in package building.

Now we need to navigate in PowerShell to the project root folder, i.e. the folder containing RedButton.csproj. Then, we need to key in the following command to run it.

nuget spec

If the command is successfully executed, there will be a message saying “Created ‘RedButton.nuspec’ successfully.”

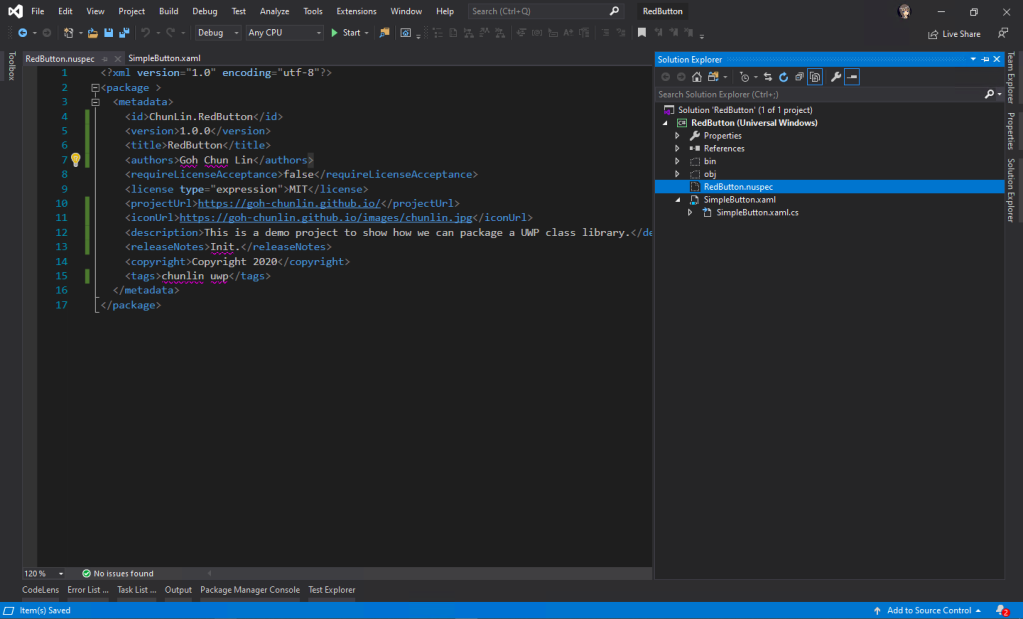

Now, we can open the RedButton.nuspec in Visual Studio. Take note that the file itself is not yet included in the solution. So we need to make sure we have enabled the “Show All Files” in the Solution Explorer to see the NuSpec file.

After that, we need to update the NuSpec file so that all of the $propertyName$ values are replaced properly. One of the values, id, must be unique across nuget.org and following the naming conventions here. Microsoft provides a very detailed explanation on each of the element in the NuSpec file. Please refer to it and follow its guidelines when you are updating the file.

Step 4: Connect with GitHub and Azure DevOps

In order to automate the publish of our package to the NuGet, we will need to implement Continuous Integration. Here, the tools that we will be using are GitHub and Azure DevOps.

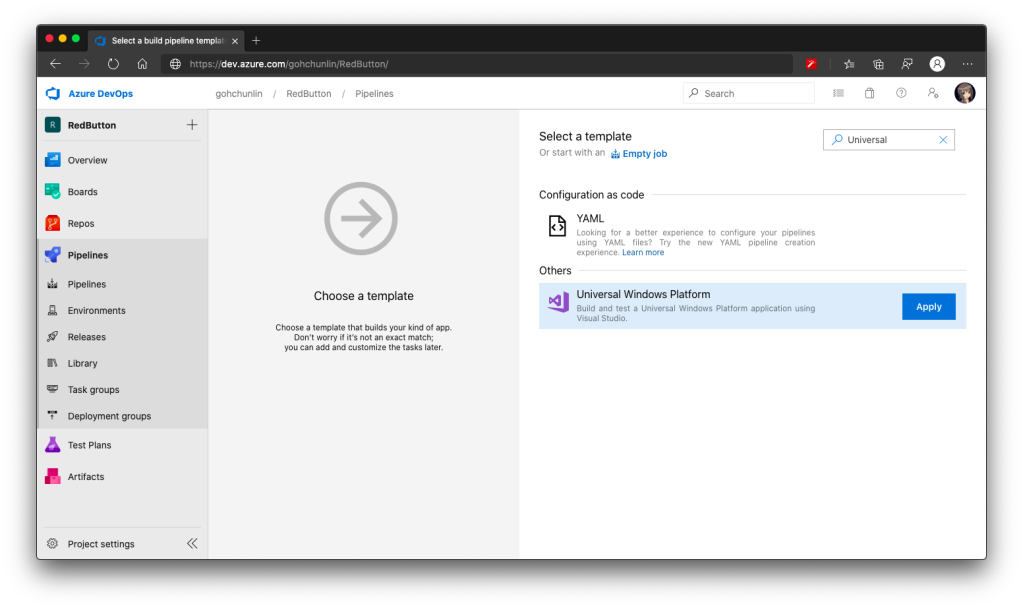

After committing our codes to GitHub, we will proceed to setup the Azure DevOps pipeline.

Firstly, we can make use of the UWP build template available on the Azure DevOps.

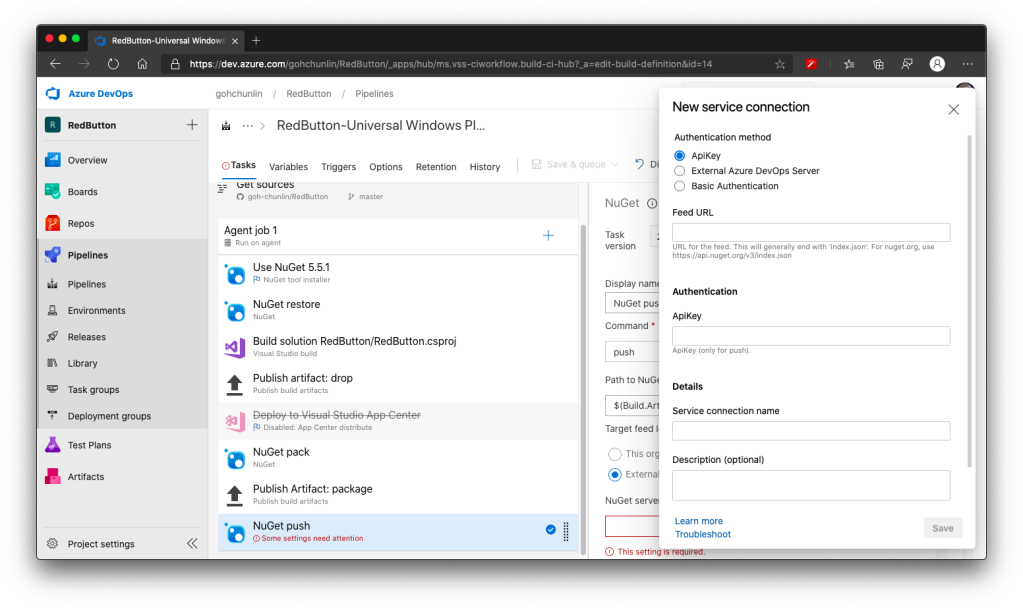

At the time I am writing this port, there are 5 tasks in the agent job:

- Use NuGet 4.4.1;

- NuGet restore **\*.sln;

- Build solution **\*.sln;

- Publish artifact: drop;

- Deploy to Visual Studio App Center.

Take note that the NuGet version by default is 4.4.1, which is rather old and new things like <license> element in our NuSpec file will not be accepted. Hence, to solve this problem, we can refer to the list of available NuGet version at https://dist.nuget.org/tools.json.

At the time this post is written in April 2020, the latest released and blessed NuGet version is 5.5.1. So we will change it to 5.5.1. Please update it to any other latest number according to your needs and the time you read this post.

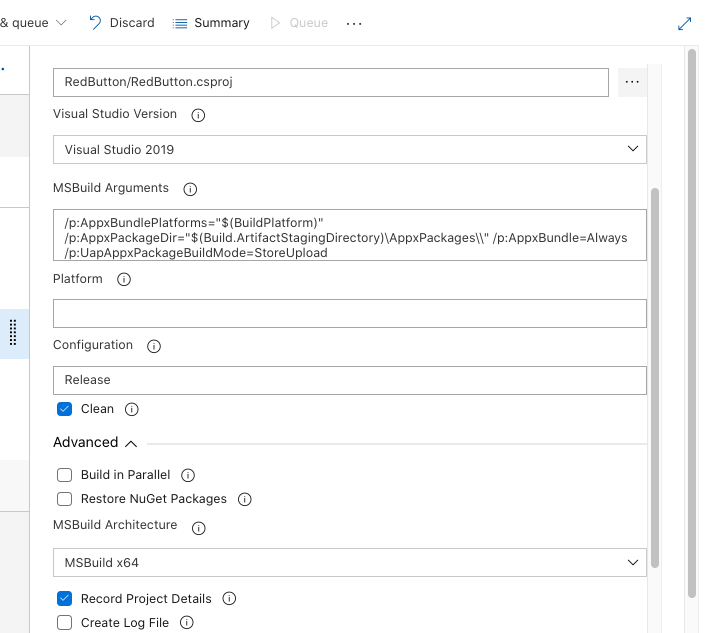

After that, for the second task, we need to update its “Path to solution, packages.config, or project.json” to be pointing at “RedButton\RedButton.csproj”.

Similarly, for the “Solution” field in the third task, we also need to point it to the “RedButton\RedButton.csproj”. Previously I pointed it to the RedButton folder which contains the .sln file, it will not work even though it is asking for “Solution”.

On the third task, we also need to update the “Visual Studio Version” to be “Visual Studio 2019” (or any other suitable VS for our UWP app). It seems to be not working when I was using VS2017. After that, I also updated the field “Configuration” to Release because by default it’s set to Debug and publishing Debug mode to public is not a good idea. I have also enabled “Clean” build to avoid incremental build which is not useful in my case. Finally, I changed the MSBuild Architecture to use MSBuild x64. The update of the third task is reflected on the screenshot below.

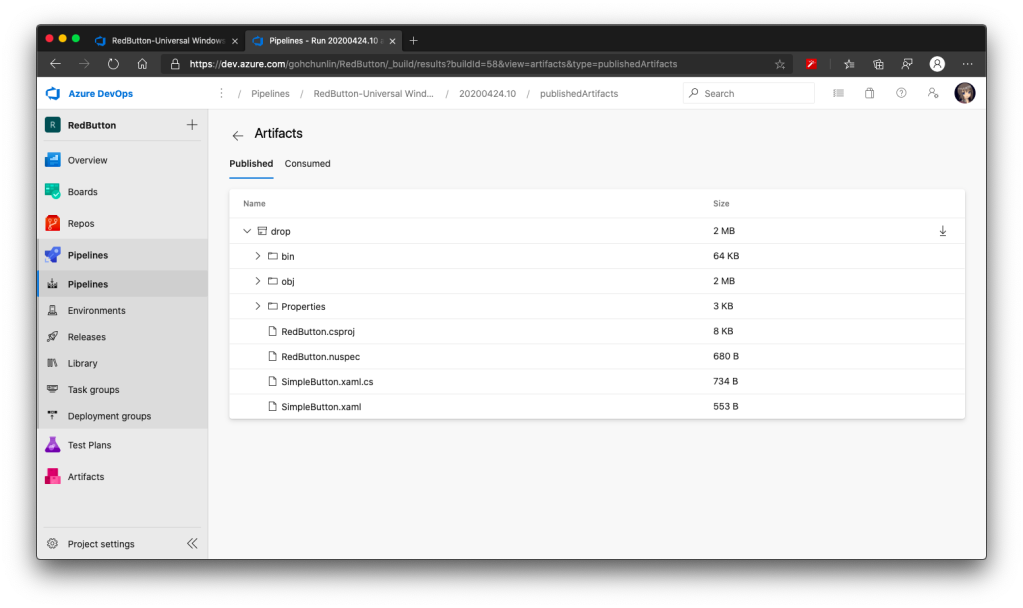

For the forth task, similarly, we also set its “Path to publish” to “RedButton”. Ah-ha, this time we are using the solution folder itself. By right, this fourth task is not relevant if we just publish our UWP class library to a NuGet server. I still keep it and set its path to publish to be the solution so that later I can view the build results of previous tasks by downloading it from the Artifact of the build.

I’d recommend to have this step because sometimes your built output folder structure may not be the same as what I have here depends on how you structure your project. Hence, based on the output folder, you many need to make some adjustments to the paths used in the Azure DevOps.

By default, the fifth task is disabled. Since we are also not going to upload our UWP app to VS App Center, so we will not work on that fifth task. Instead, we are going to add three new tasks.

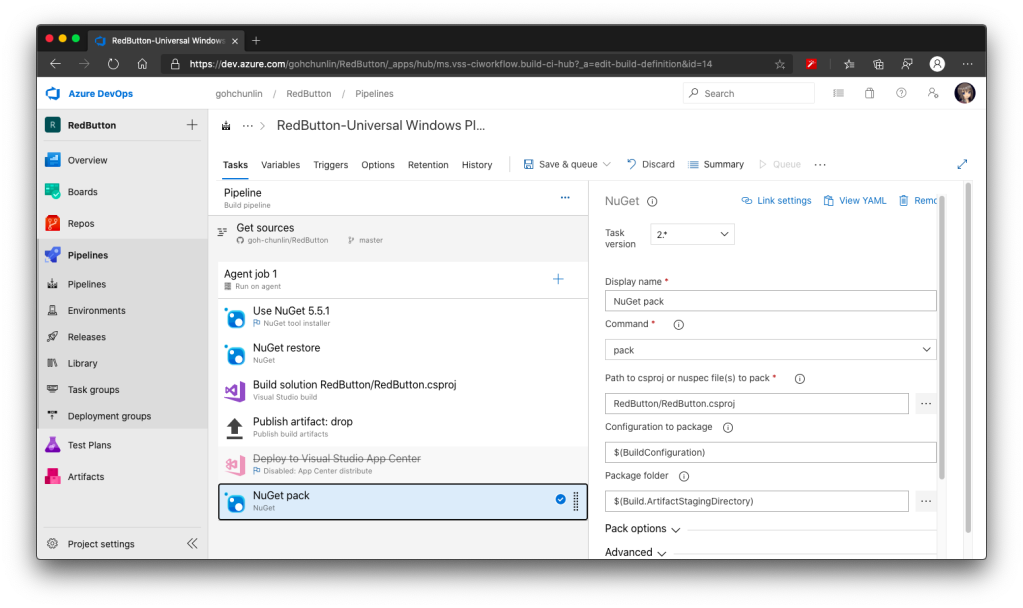

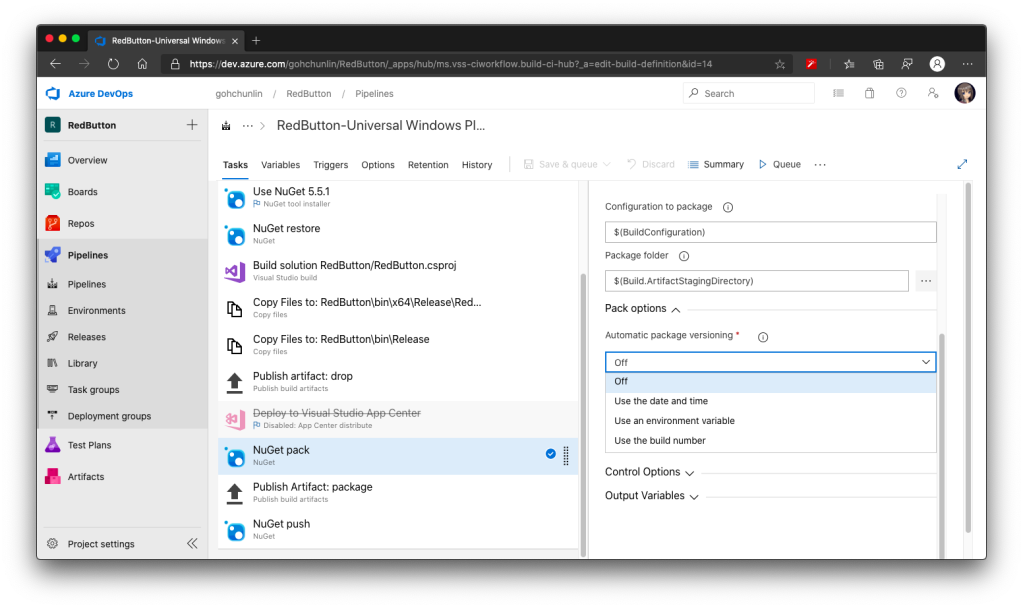

Firstly, we will introduce the NuGet pack task as the sixth task. The task in the template is by default called “NuGet restore” but we can change the command from “restore” to “pack” after adding the task, as shown in the following screenshot.

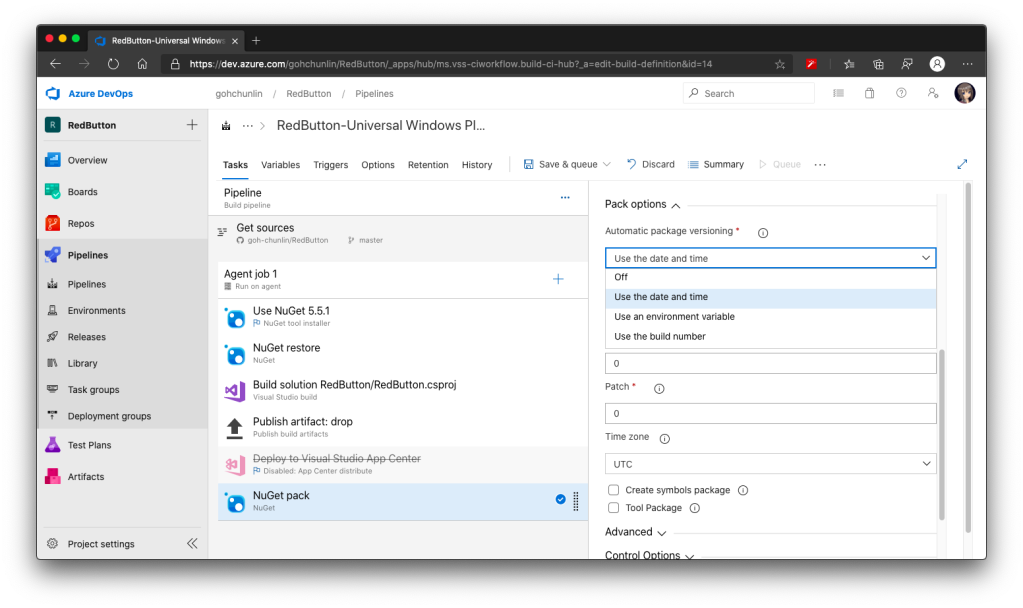

There is one more important information that we need to provide for NuGet packaging. It’s the version of our package. We can either do it manually or automatically. It’s better to automate the versioning else we may screw it up anytime down the road.

There are several ways to do auto versioning. Here, we will go with the “Date and Time” method, as shown in the screenshot below.

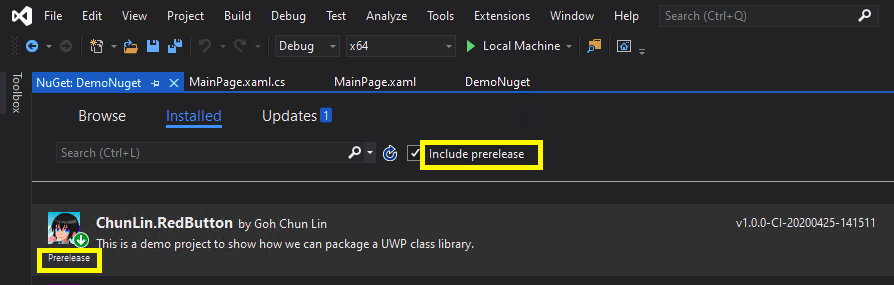

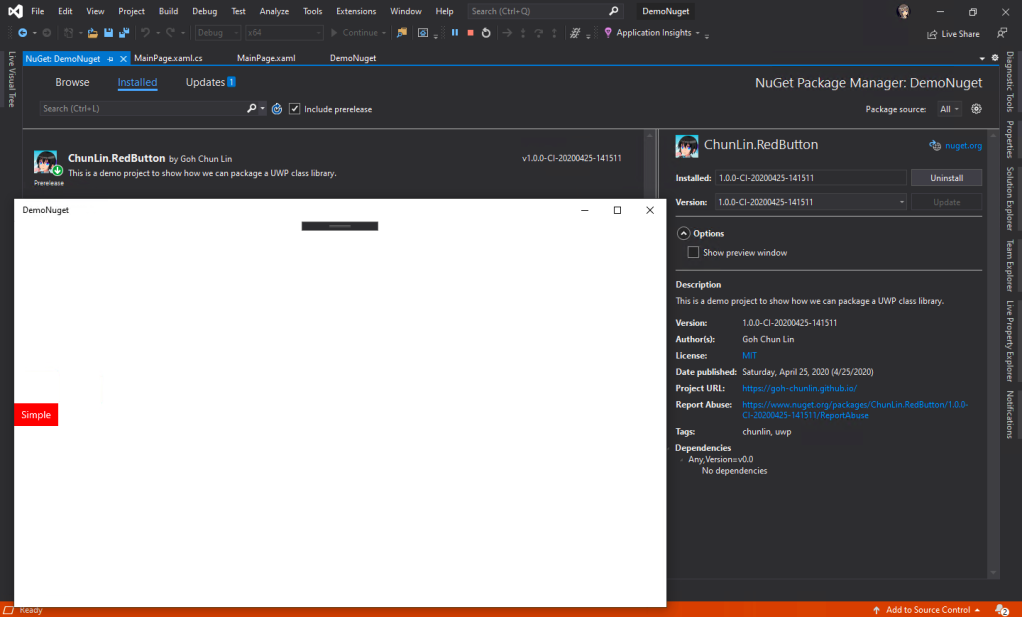

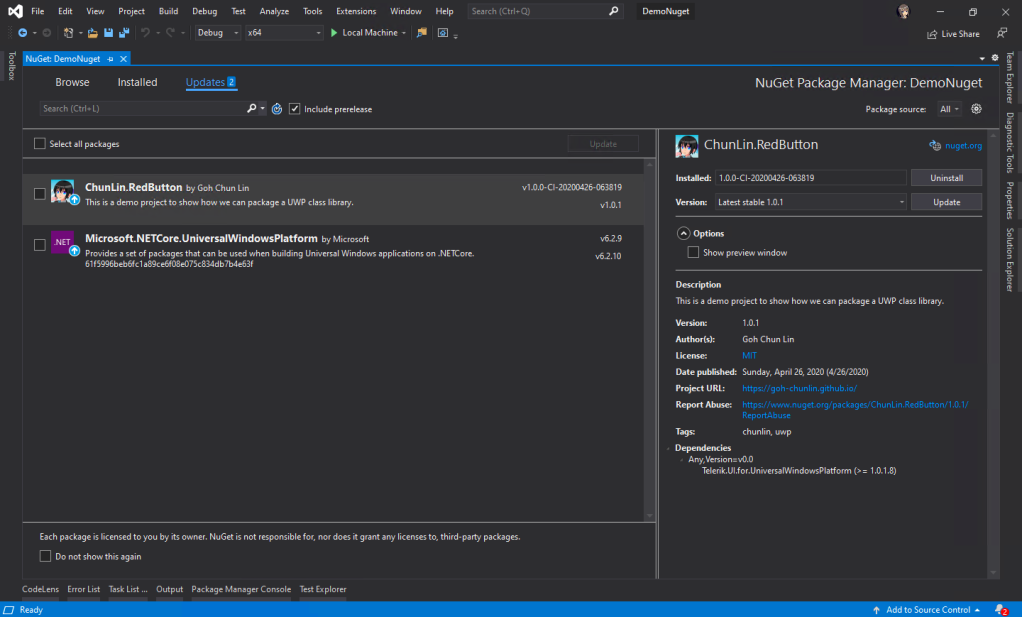

This way of versioning will append datetime at the end of our version automatically. Doing so allows us to quickly test the release on the NuGet server instead of spending additional time on updating the version number. Of course, doing so means that the releases will be categorized as pre-released which users cannot see on Visual Studio unless they check the “Include prerelease” checkbox.

Secondly, if you are also curious about the package generated by the sixth task above, you can add a task similar to the fourth task, i.e. publish the package as artifact for download later. Here, the “Path to publish” will be “$(Build.ArtifactStagingDirectory)”.

Since a NuGet package is just a zipped file, we can change its extension from .nupkg to .zip to view its content on Windows. I did the similar on MacOS but it didn’t work, so I guess it is possible on Windows only.

Thirdly, we need to introduce the NuGet push task after the task above to be the eighth task. Here, we need to set its “Path to NuGet package(s) to publish” to “$(Build.ArtifactStagingDirectory)/*.nupkg”.

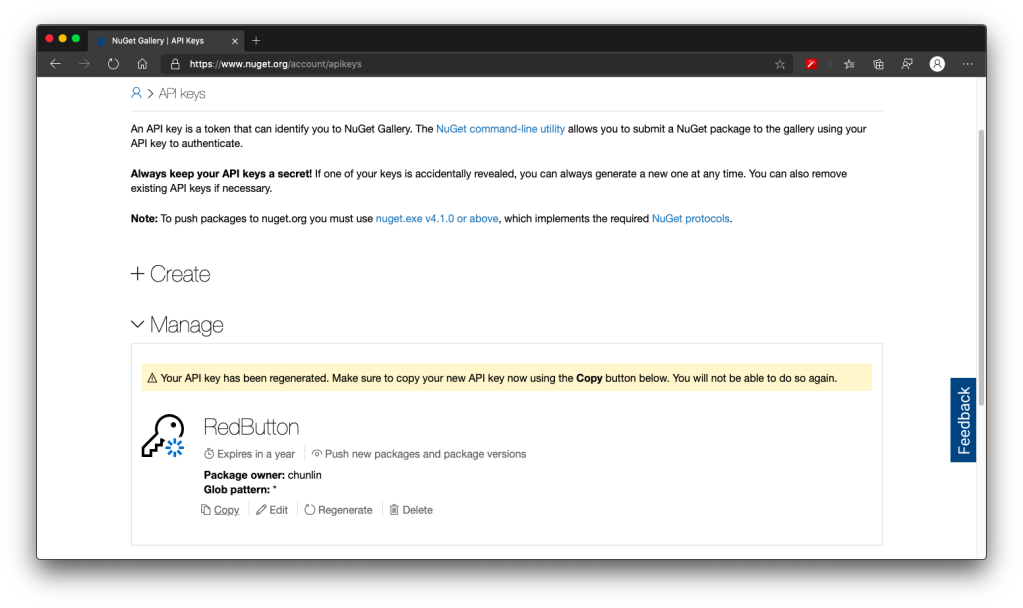

Then, we need to specify that we will publish our package to the nuget.org server which is an external NuGet server. By clicking on the “+ New” button, we can then see the following popup.

Azure DevOps is so friendly that it tells us that “For nuget.org, use https://api.nuget.org/v3/index.json”, we will thus enter that URL as the Feed URL.

With this NuGet push task setup successfully, we can proceed to save and run this pipeline.

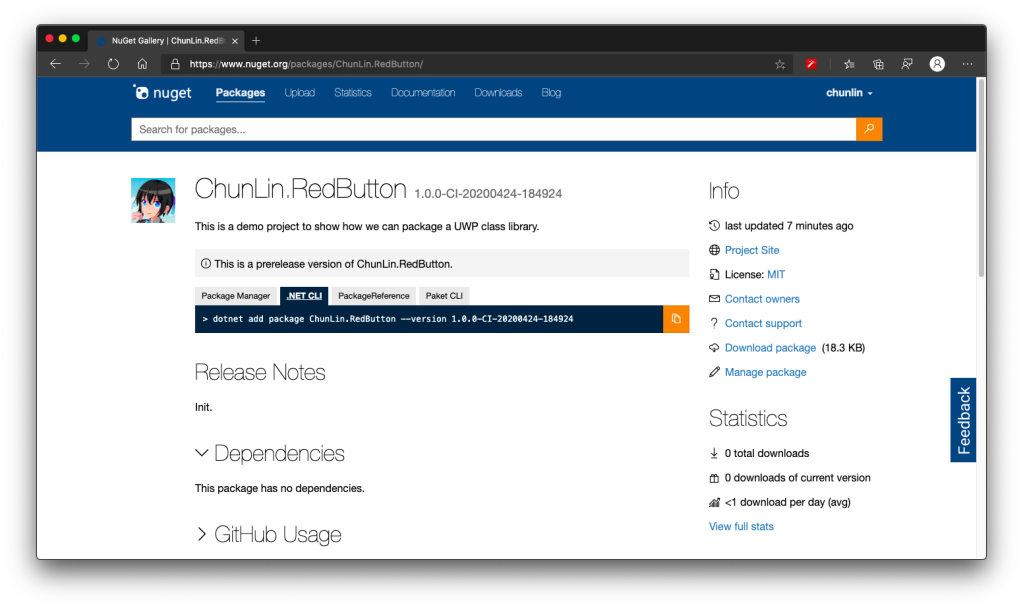

After the tasks are all executed smoothly and successfully, we shall see our pre-released NuGet package available on the nuget.org website. Note that it requires an amount of time to do package validating before public can use the new package.

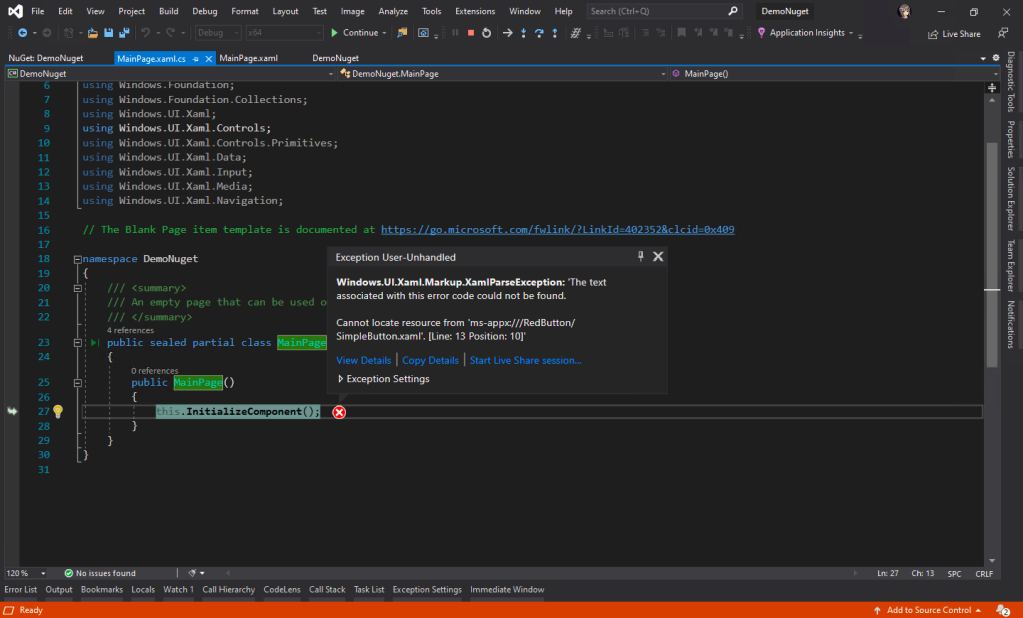

This is not a happy ending yet. In fact, if we try this NuGet package, we will see the following error which states that it “cannot locate resource from ‘ms-appx:///RedButton/SimpleButton.xaml’.”

So what is happening here?

In fact, according to an answer on StackOverflow which later leads me to another post about Windows Phone 8.1, we need to make sure the file XAML Binary File (XBF) of our XAML component is put in the NuGet package as well.

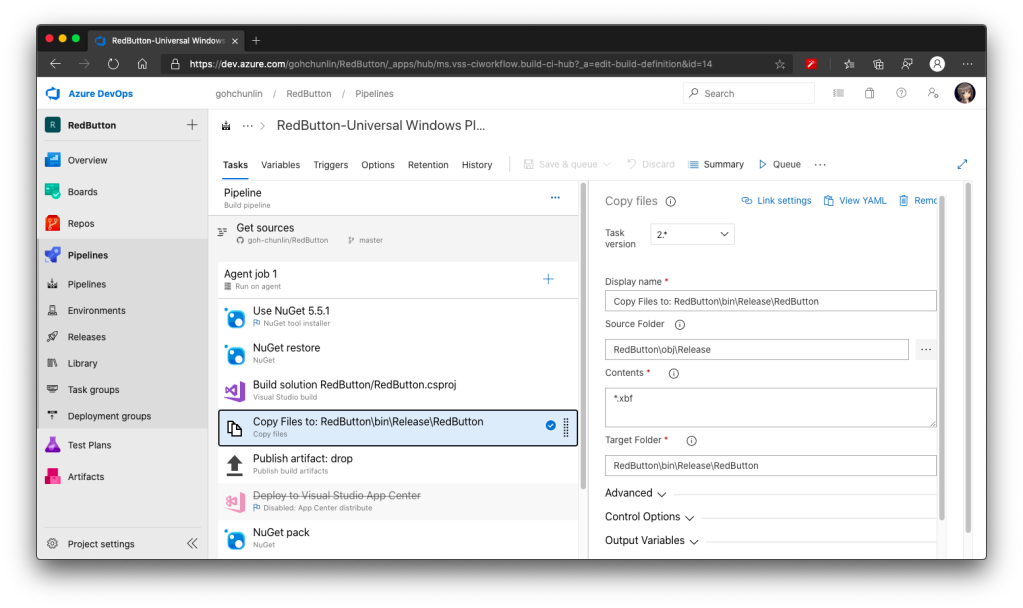

To do so, we have to introduce a new task right after the third task, which is to copy the XBF file from obj folder to the Release folder in the bin folder, as shown in the following screenshot.

Step 5: Targeting Framework

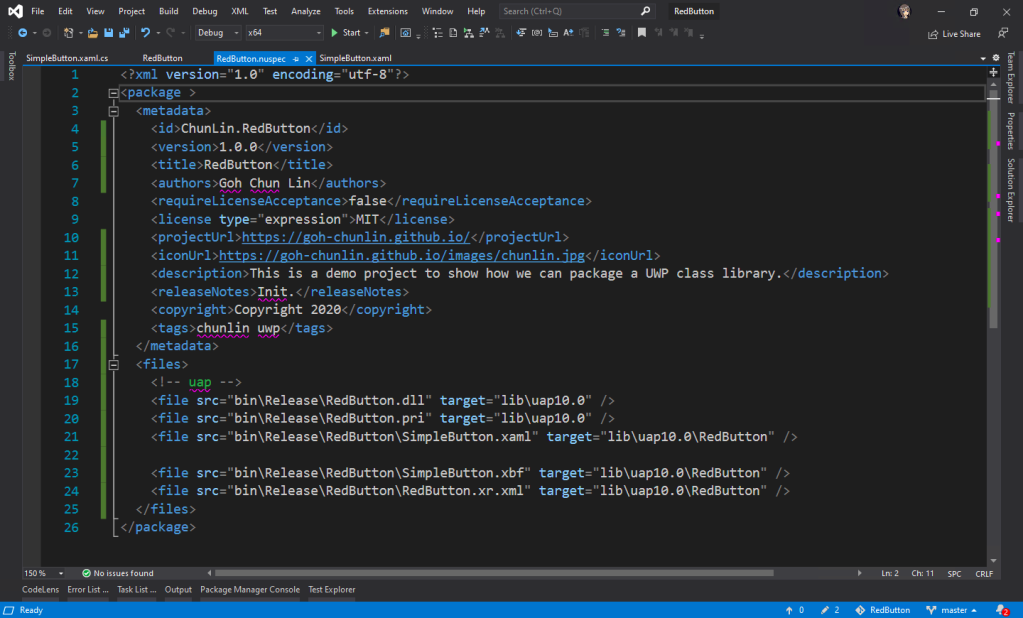

Before we make our NuGet package to work, we need to specify the framework it is targeting at. To do so, we need to introduce the <files> to our NuSpec.

So, the NuSpec should look something as follows now.

Now with this, we can use our prerelease version of our UWP control in another UWP project through NuGet.

Step 6: Platform Release Issues

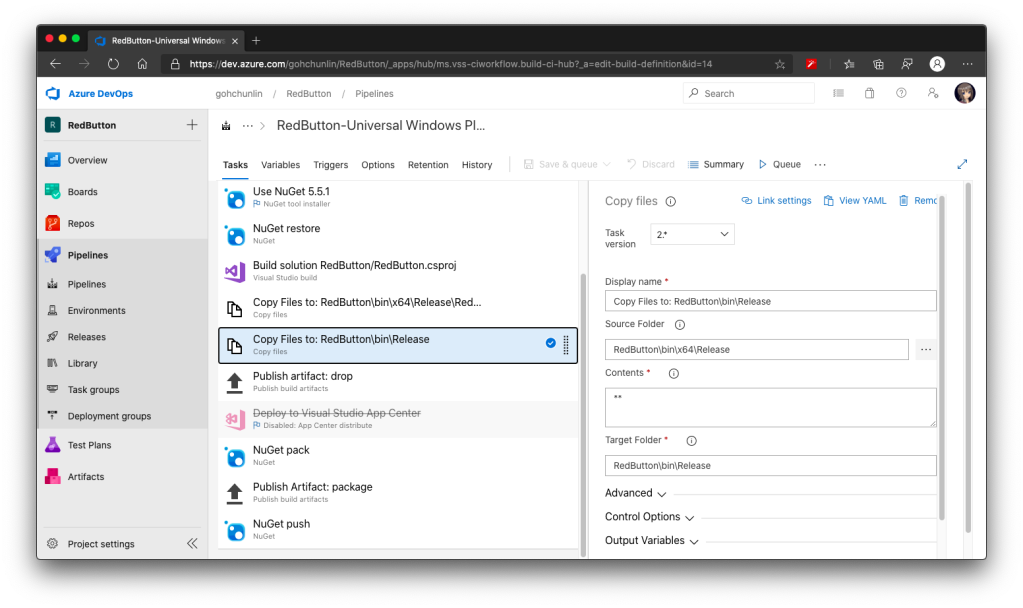

There will be time which requires us to specify the Platform to be, for example, x64 in the third task of the Azure DevOps pipeline above. That will result in putting the Release folder in both obj and bin to be moved to obj\x64 and bin\x64, respectively. This will undoubtedly make the entire build pipeline fails.

Hence we need to update the paths in the Copy File task (the fourth task) and add another Copy File task to move the Release folder back to be directly under the bin directory. Without doing this, the nuget pack task will fail as well.

Step 7: Dependencies

If our control relies on the other NuGet packages, for example Telerik.UI.for.UniversalWindowsPlatform, then we have to include them too inside the <metadata> in the NuSpec, as shown below.

<dependencies>

<dependency id="Telerik.UI.for.UniversalWindowsPlatform" version="1.0.1.8" />

<dependencies>

Step 8: True Release

Okay, after we are happy with the prerelease of our NuGet package, we can officially release our package on the NuGet server. To do so, simply turn off the automatic package versioning on Azure DevOps, as shown in the screenshot below.

With this step, now when we run the pipeline again, it will generate a new release of the package without the prerelease label. The version number will follow the version we provide in the NuSpec file.

Journey: 3 Days 3 Nights

The motivation of this project comes from a problem I encounter at workplace because our UWP class library could not be used whenever we consumed it as a NuGet package. This was also the time when Google and StackOverflow didn’t have proper answers on this.

Hence, it took me 1 working day and 2 days during weekend to research and come up with the steps above. Hopefully with my post, people around the world can easily pickup this skill without wasting too much effort and time.

Finally, I’d like to thank my senior Riza Marhaban for encouraging me in this tough period. Step 7 above is actually his idea as well. In addition, I have friend encouraging me online too in this tough Covid-19 lockdown. Thanks to all of them, I manage to learn something new in this weekend.

References

- .nuspec reference;

- How should we pack Universal Windows Class Libraries with NuGet?

- How to reference a UserControl from an external class library (through a NuGet Package)?

- Windows Phone 8.1 NuGet packages with XAML components;

- Manual Package Download;

- Create UWP packages (C#);

- Versioning NuGet packages in a continuous delivery world: part 1;

- Versioning NuGet packages in a continuous delivery world: part 2.