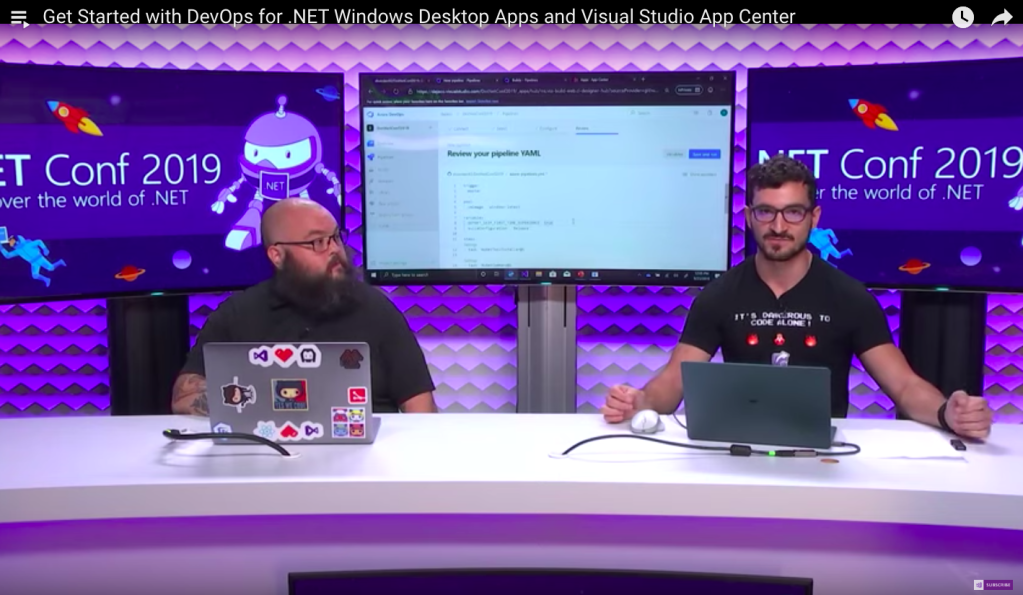

In September, .NET Core 3.0 was announced in the official .NET Conf 2019. Happily, I’m invited to be speaker in .NET Conf Singapore happening in BLOCK71. I am one the organisers of the event, so theoretically speaking, I invited myself.

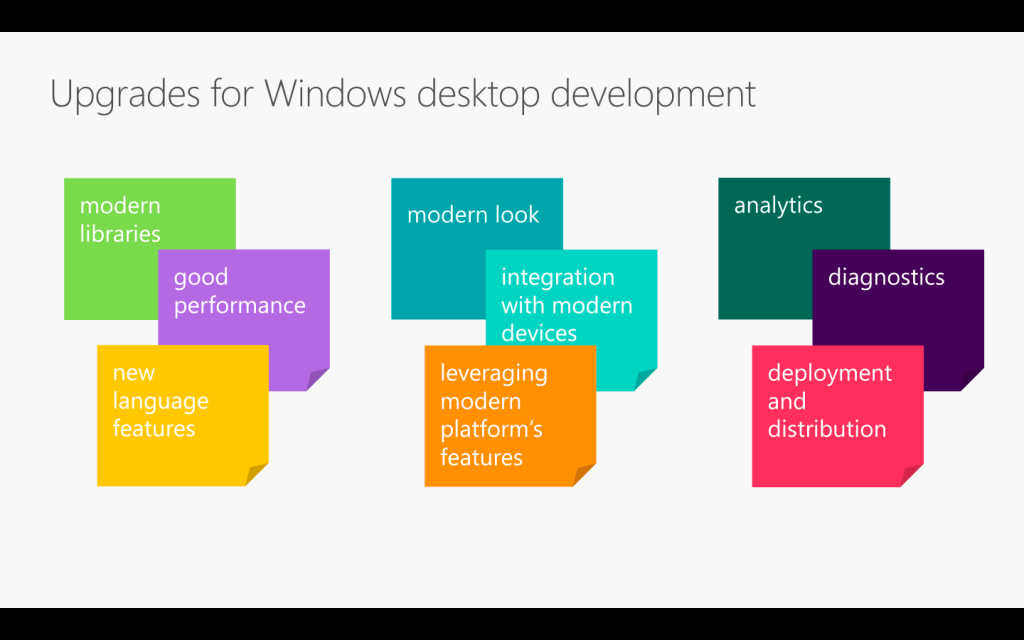

The topic that I delivered in the event is “Development and DevOps of Desktop Apps with .NET Core 3.0”. It is a 45-minute talk combining the content from the following three talks.

- Modernizing .NET Desktop Applications with .NET Core;

- Tour What’s New for XAML Tools & XAML Islands in VS2019;

- Get Started with DevOps for .NET Windows Desktop Apps and Visual Studio App Center.

If you watch the videos above, the total length is about 70 minutes. So covering three of them in a 45-minute talk is a challenge to me. Luckily, I have Sabrina to help me out by co-speaking with me.

If you have missed our session, don’t worry, I have uploaded the recordings of the .NET Conf Singapore 2019 to the YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VX-bAcBOWw&list=PLJEtXrSgWKZqkaYgY3PxBjRbA8O2vKEL7

If you have watched our session, you will realise it’s quite different from the official .NET Conf. In this post, I am going to brief you through about my thoughts and development process of our talk content.

Let’s Hashtag Together!

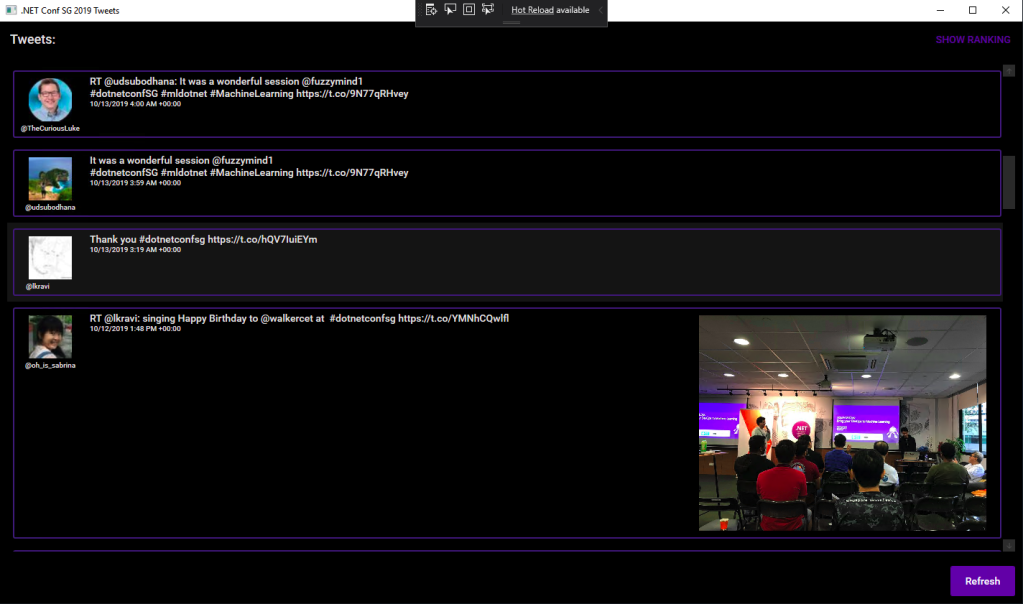

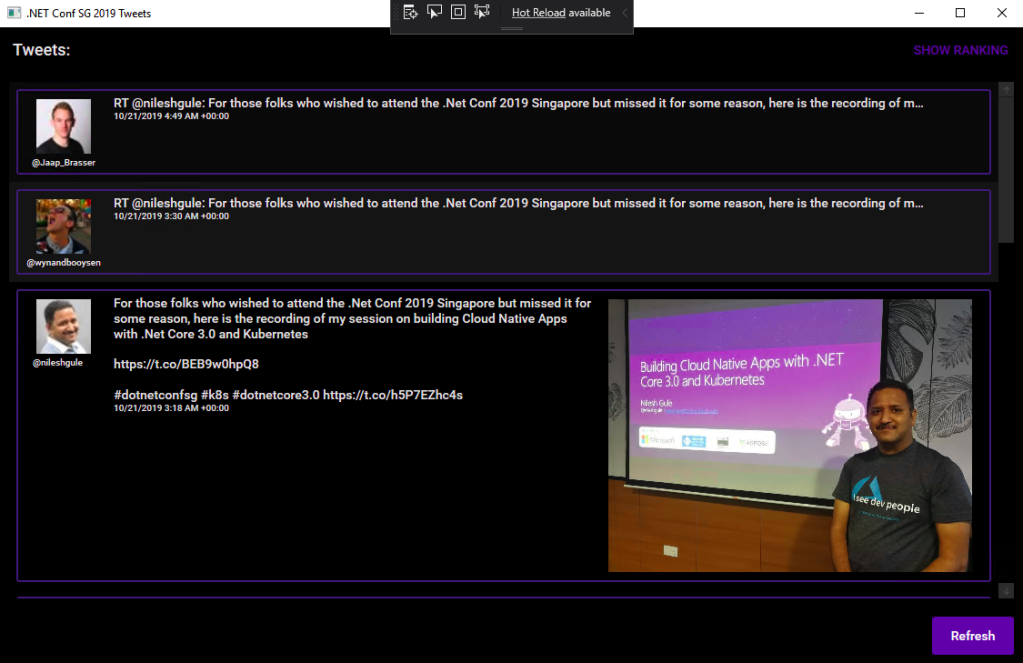

In order to make the conference to be more engaging, after discussing with Sabrina, I came out with a desktop app which will shows the recent tweets having #dotnetconfsg hashtag, which looks like the following.

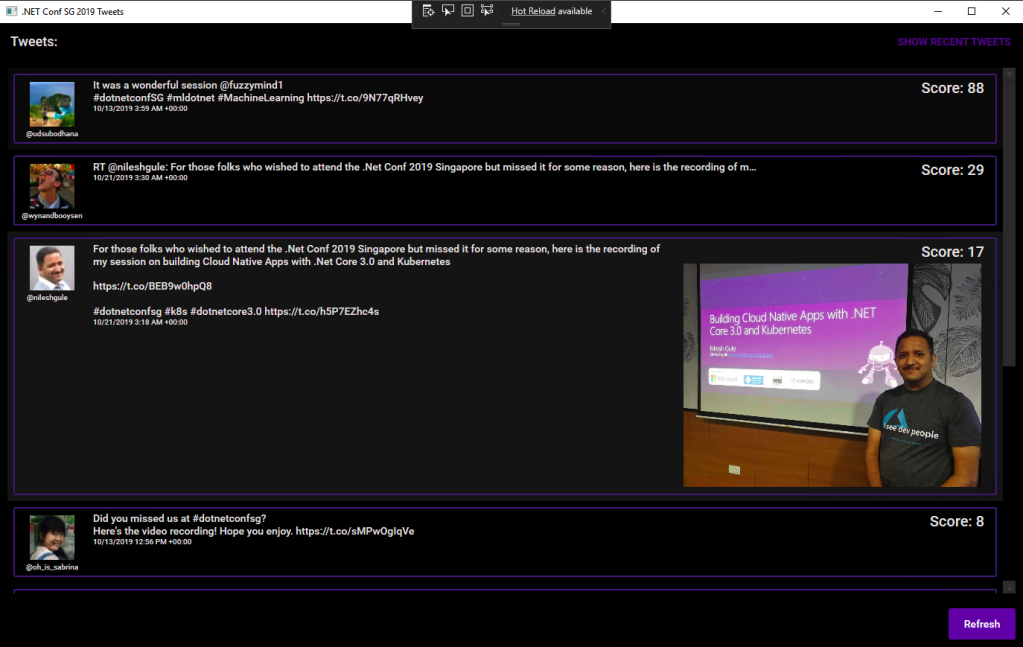

To make this “game” more interesting, I announced that the top four participants who earn the highest scores would receive prizes from me. The formula to calculate the score is basically

- +1 point for one tweet;

- +5 point for one retweet of the tweet;

- +5 point for one like of the tweet.

Throughout the conference, we thus had seen a huge number of tweets about our event and speakers. Some of them even tweeted with great photos (I should have given 5 points for great photos too).

In our talk, we used this desktop app as our sample. The app is built in .NET Framework 4.7. Sabrina started the demo with showing how we can modernise it to a .NET Core desktop app. I then covered a bit about Hot Reload, the runtime tools (the small little black bar on top of locally launched WPF app), and DevOps part of desktop app.

Starting from .NET Framework 4.7

After the talk, I redo the project to make it nicer. I have also published the code on GitHub: https://github.com/goh-chunlin/DotNetConfSgTweetsDashboard

I am using the Tweetinvi library to retrieve the tweets easily. I originally tried calling the Tweeter APIs directly from C# and it’s a painful experience. Instead of wasting resources on researching the Tweeter APIs, I change to use Tweetinvi because it allows me to easily get the tweets in just two lines of codes.

To improve the GUI, I use the Material Design in XAML Toolkit. So, I can easily change the WPF application to have dark mode. This is very important to me because I realise light mode isn’t displayed well on the projected screen during the event. So, it now looks as shown in the following screenshot.

By clicking on the “Show Ranking” button at the top-right corner, we can easily tell the scores received by the participants.

Migrating to .NET Core 3.0

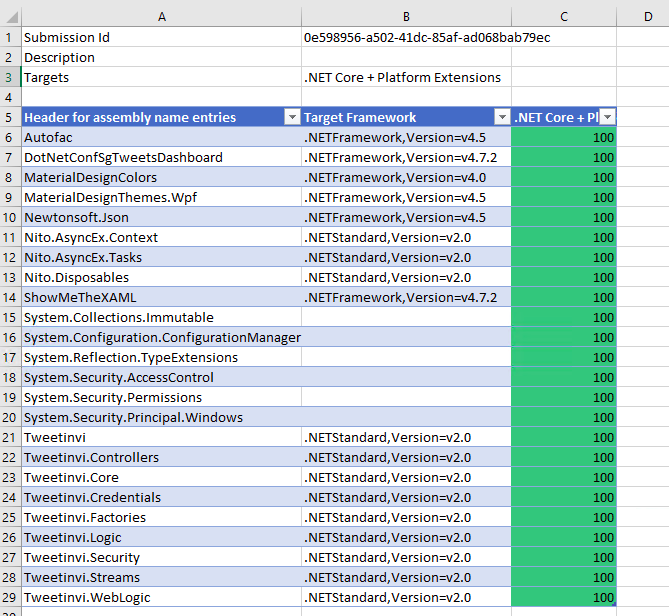

Now with many third-party libraries used in our WPF application, is the desktop app still compatible with .NET Core? Well, to answer this question, there is a tool from Microsoft called Portability Analyzer can give us a detail report on the set of APIs referenced in our apps that are not yet available in NET Core 3.0.

After downloading it and using it to check our application above, we received the following report.

The Excel report comes with three tabs, i.e. Portability Summary (the one shown above), Details (empty), and Missing assemblies. There is one item in the report Missing assemblies though, as shown below.

Interestingly, if we refer to the .NET API Portability GitHub repo, we will see an issue filed by Alicia Li. There are many doubts over this tab.

However, if we proceed to use try-convert to migrate our WPF application from .NET Framework to .NET Core, it will be a successful conversion, as shown in the screenshot below.

The try-convert tool is an open-source tool that helps us to migrate .NET Framework projects to .NET Core. After installing it, we need to restart the Command Prompt to use it.

The following screenshot shows how the app looks like after being migrated to .NET Core 3.0. Nothing significant is changed. If you would like to find out what have been changed, please visit the commit of this project on GitHub.

XAML Islands

There is another thing that I shared in my talk is about XAML Islands. In fact, I talked about XAML Islands in Microsoft Insider Dev Tour too when I was sharing about WinUI.

XAML Islands is a feature that allows us to host UWP controls in non-UWP desktop applications. The reason of having it is to improve the UX of existing Win32 apps by leveraging UWP controls.

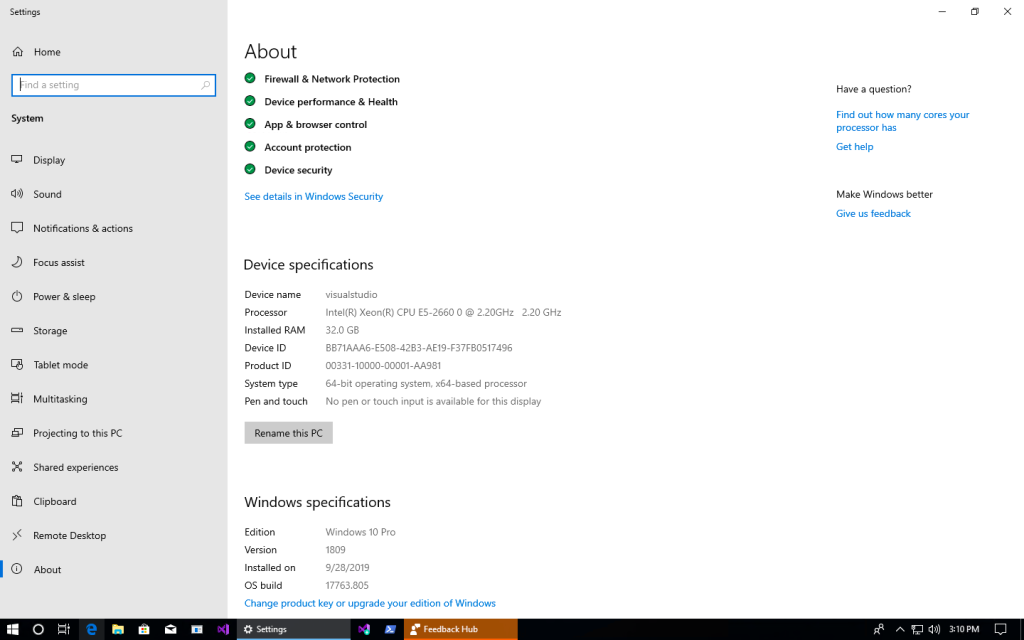

Although the documentation says it is enabled only starting from Windows 10, version 1903. However, if you are using version 1809, XAML Islands feature is also available already, just that not yet stable. So, the best choice is still using version 1903 and above.

In my presentation, since I was using the Windows 10 image hosted on Microsoft Azure VM, the best version I could get is 1809.

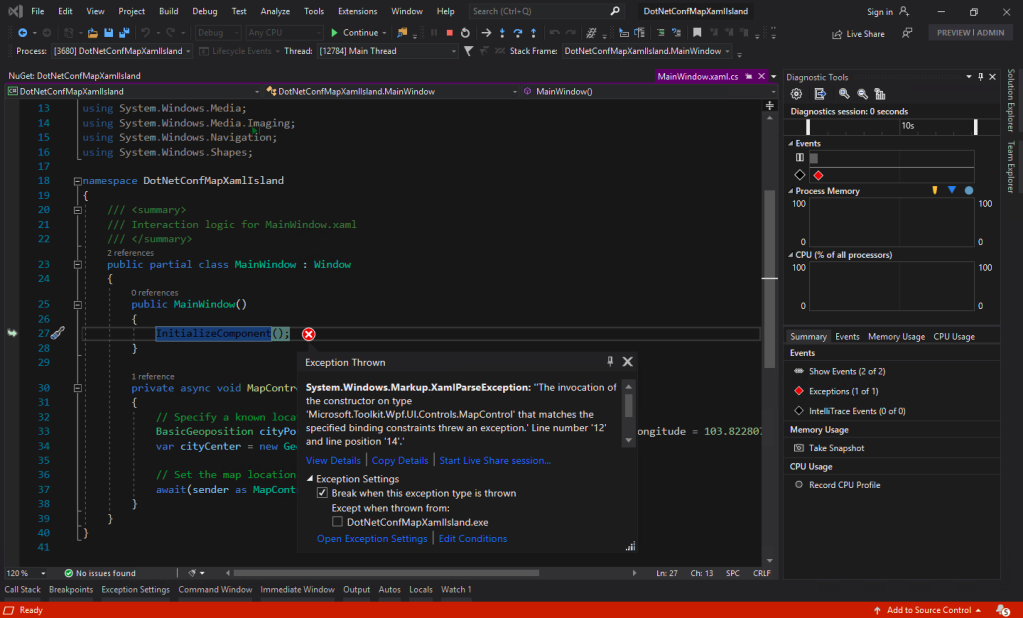

The quick-start way to use an XAML Island inside a WPF app is to use the NuGet packages from Microsoft. The one I am using is Microsoft.Toolkit.Wpf.UI.Controls, which has wrapper classes for 1st party controls, such as the InkCanvas, InkToolbar, MapControl, and MediaPlayerElement, all for WPF.

You may ask why I am using version 5.1.1 of the Microsoft.Toolkit.Wpf.UI.Controls. On the day of .NET Conf Singapore, the version 6.0 (Preview 9.1) of it is already out. However, when I try to use the library, it threw the exception, as shown in the screenshot below.

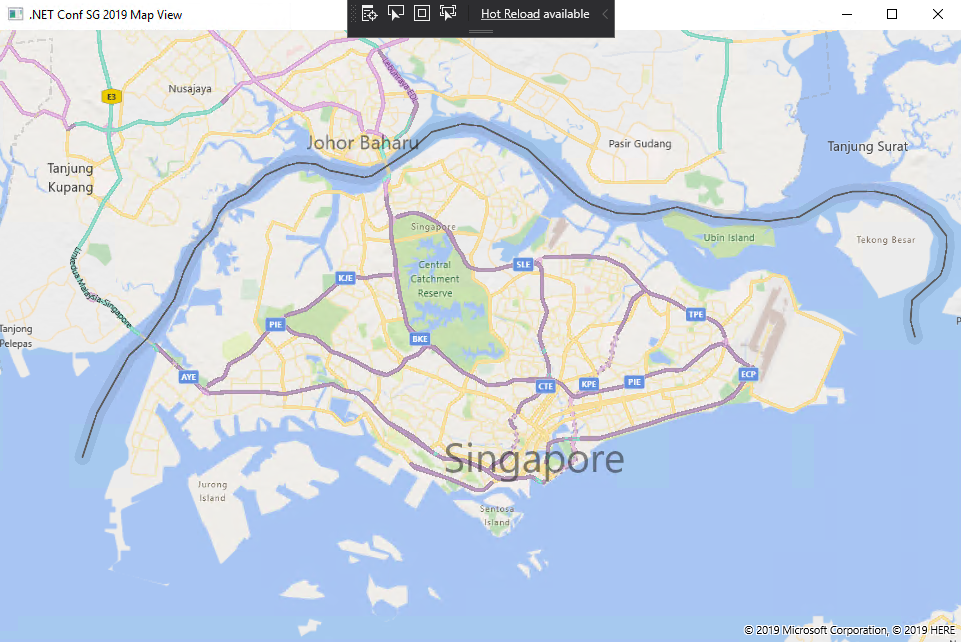

I could only demonstrated how I used the MapControl in a WPF app with XAML Islands.

Creating Build Pipeline in Azure DevOps

Now, with the codes of our WPF application on GitHub, we can create a Build pipeline for the app on Azure DevOps. This is not a new feature but it is nice to see how we can now build a .NET Core WPF app on Azure DevOps.

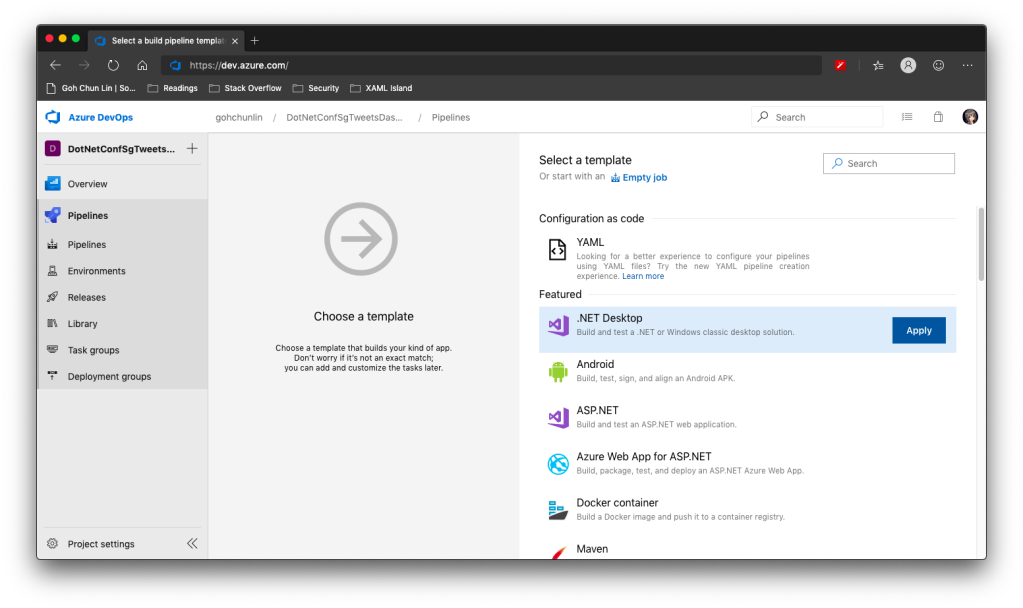

There is a template available on Azure DevOps to build .NET Desktop app.

However, before we proceed to start the build, we need to make a few changes to it.

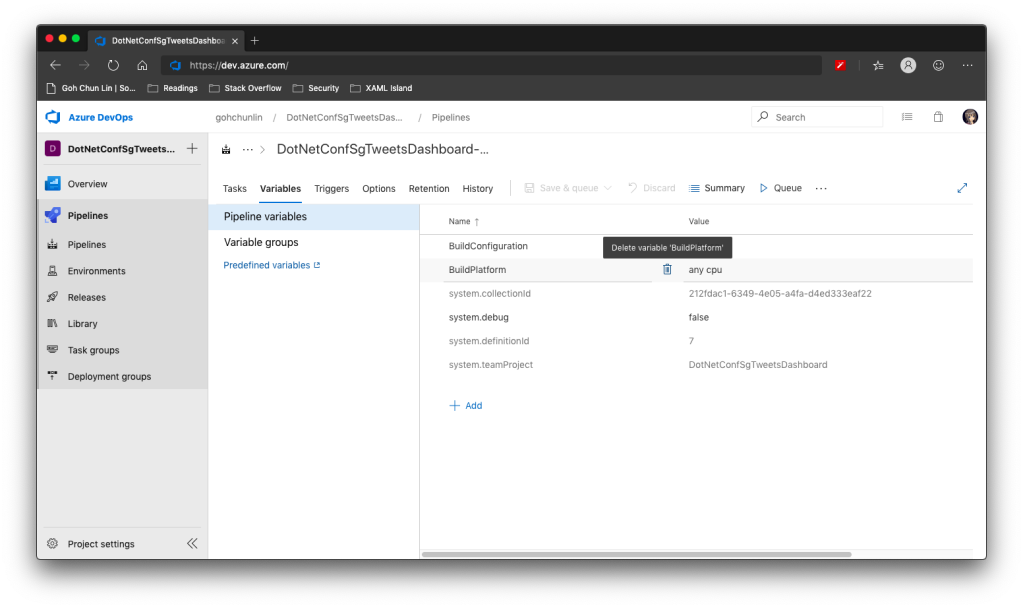

Since we will be using dotnet publish later, so the BuildPlatform variable is not necessary and can be removed.

Instead, we need to add a new variable called DOTNET_SKIP_FIRST_TIME_EXPERIENCE and set it to true. This is to speed up the build process because by default when we run any .NET Core SDK command on Azure DevOps, it does some caching. However, now we are running this on a hosted build agent, so this caching will never be useful because the agent will be discarded right after the build is completed. Thanks Daniel Jacobson for highlighting this in his video.

After that, we need to remove all the default steps because we need to start from scratch for .NET Core.

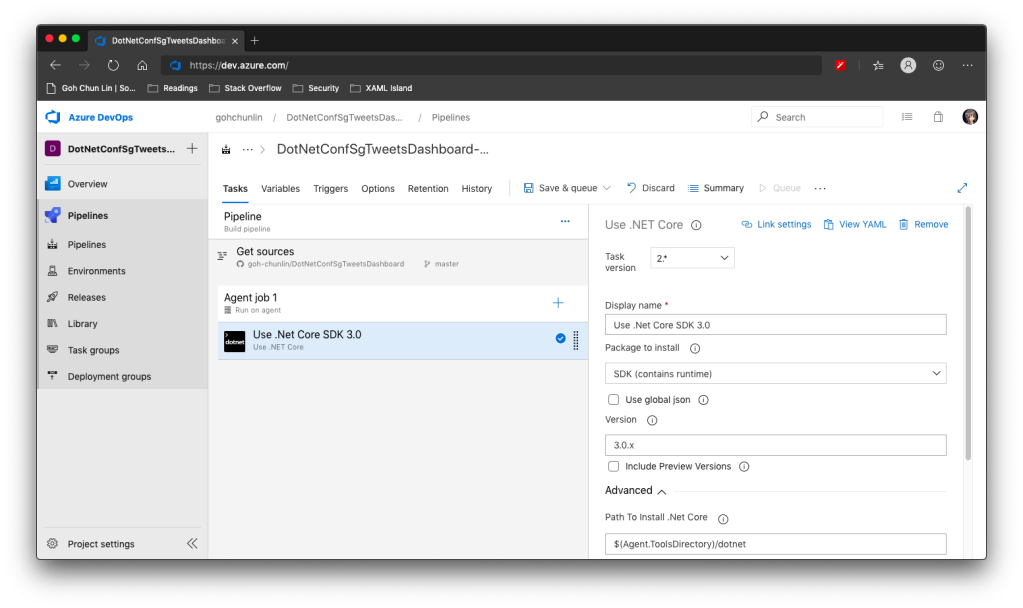

The first step is to install .NET Core SDK 3.0. Remember to state “3.0.x” as the version otherwise if there is a minor update to .NET Core 3.0, we will still be using the outdated one to build.

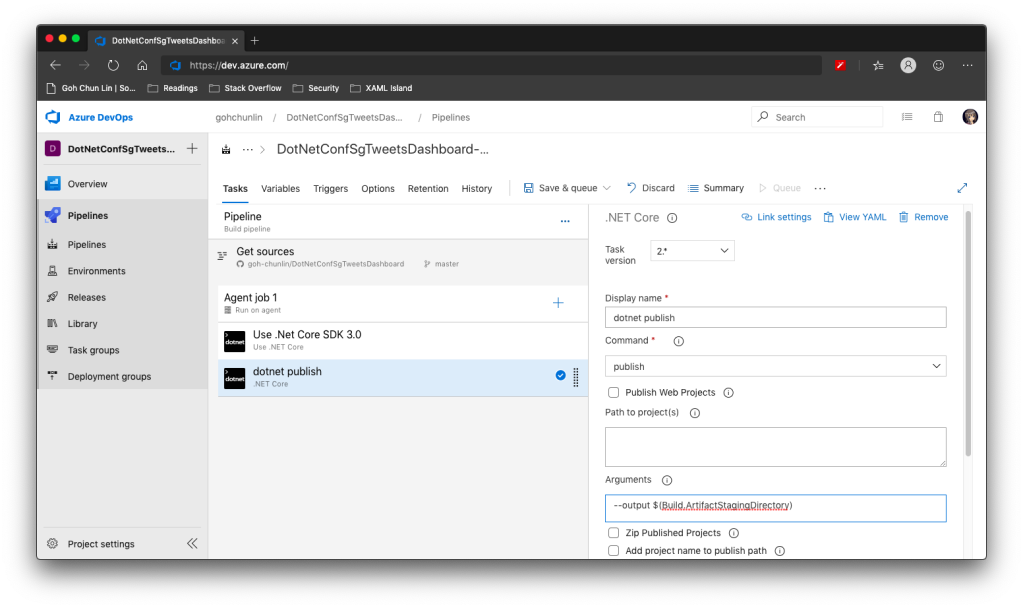

After that, we are going to do dotnet publish.

Starting with .NET Core 2.0, we don’t have to run dotnet restore because it’s run implicitly by all commands that require a restore to occur. Also dotnet publish will build the project, so we do not need to run dotnet build.

Since this is a WPF project, so we have to uncheck the “Publish Web Projects” checkbox, together with the other two checkboxes “Zip Published Projects” and “Add project name to publish path”, as shown in the screenshot below.

We also need to specify the output of the artifacts. We will put it in a directory known as $(Build.ArtifactStagingDirectory). This is actually a pre-defined variable that we can find in the Azure DevOps documentation. There is a link to this document in the Variables tab.

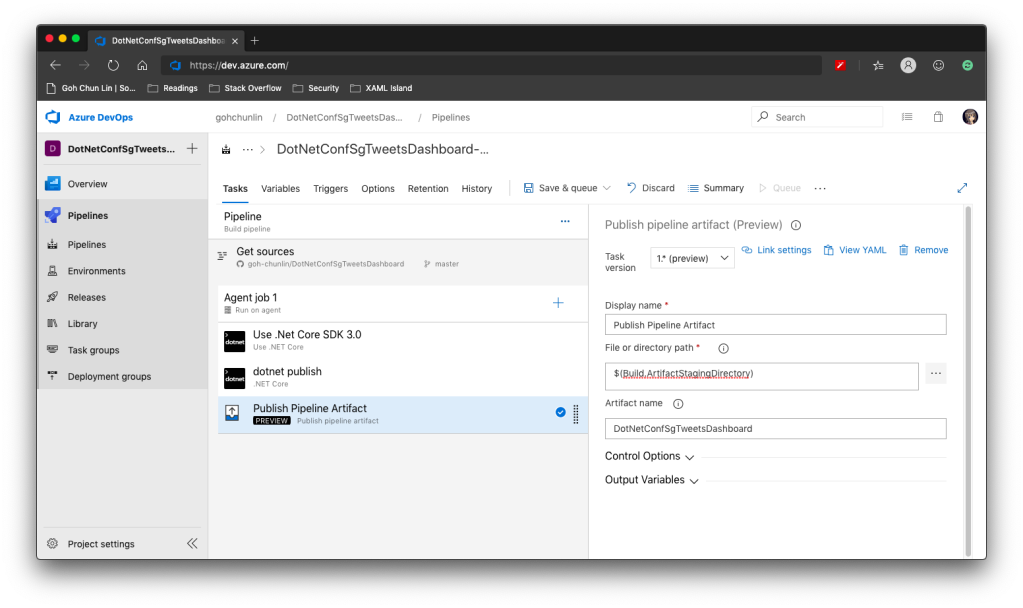

Now we proceed to add the next step, which is to publish the artifact. Here we specify $(Build.ArtifactStagingDirectory) as the path of the directory to publish. Then we also specify a user friendly name for the artifact.

Now we can click the “Save & queue” to run this pipeline.

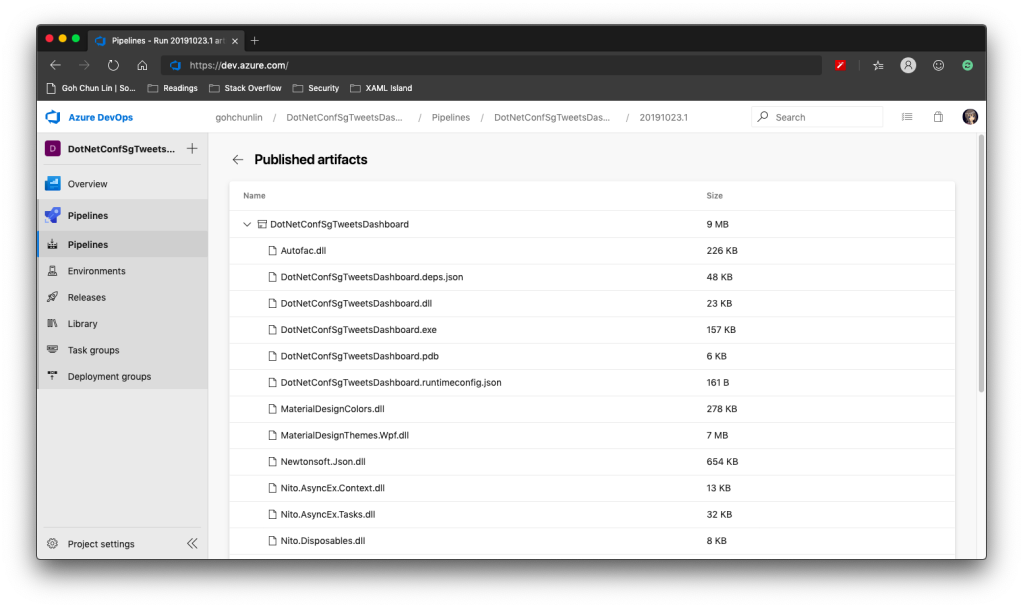

In the published artifact, we will see the following.

Wow, there are a lot of DLLs! The .exe file alone is only 157KB.

Fortunately, starting from .NET Core 3.0, as long as we specify the following in our csproj file, it will produce a single .exe file.

<PublishSingleFile>true</PublishSingleFile>

However, there is one more thing to take note is that if we miss out the <RuntimeIdentifier>, there will be an error NETSDK1097 which says, “It is not supported to publish an application to a single-file without specifying a RuntimeIdentifier. Please either specify a RuntimeIdentifier or set PublishSingleFile to false.”

<RuntimeIdentifier>win-x86</RuntimeIdentifier>

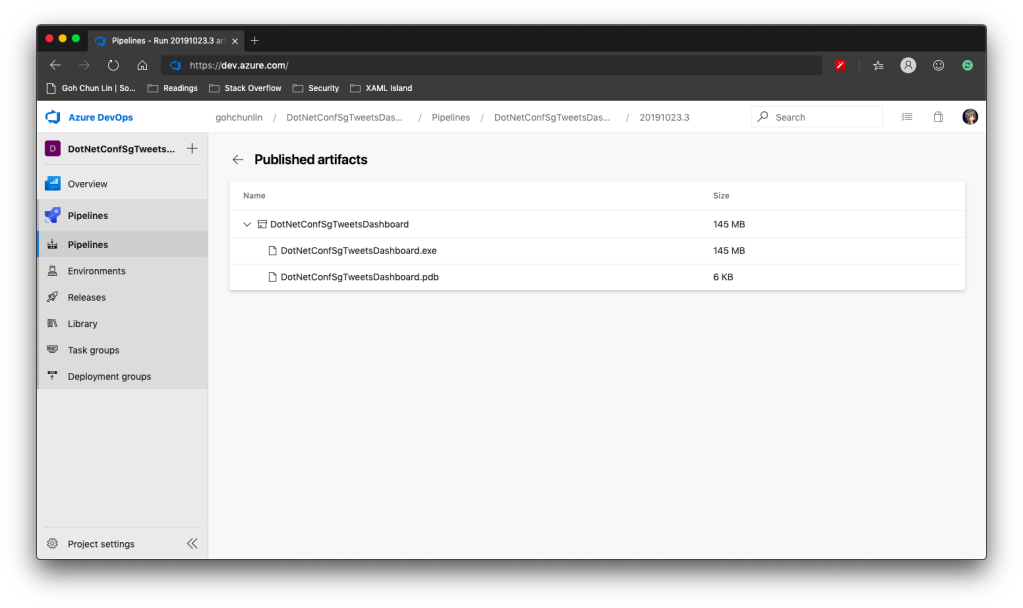

With this change, when we run the Build pipeline again, we get the following.

We now only have one .exe file but its size has grown from 157KB to 145MB!

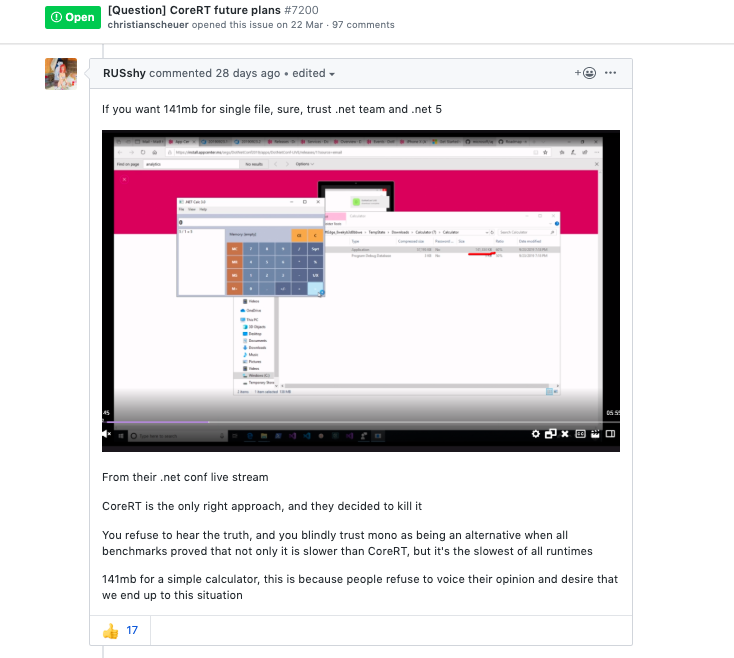

There is mixed feeling for developers in .NET CoreRT project. In their discussion about CoreRT future, they’re disappointed about CoreRT not being mentioned, instead PublishSingleFile was mentioned in the .NET Conf 2019.

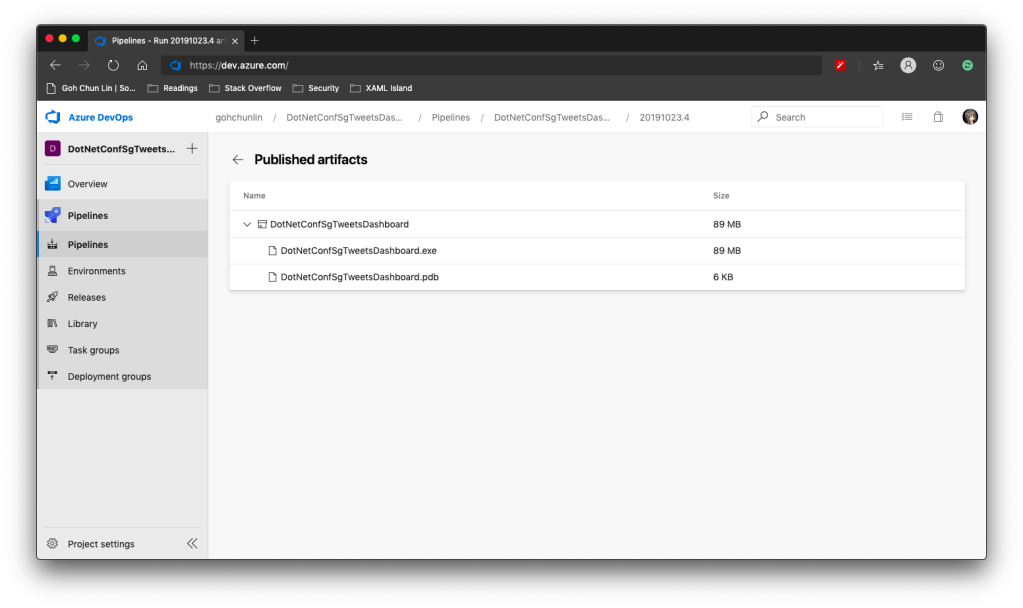

In fact, according to Scott Hanselmen’s blog post “Making a tiny .NET Core 3.0 entirely self-contained single executable”, he suggested to set <PublishTrimmed> to be true to trim out unused codes so that now the .exe will be smaller.

Cool, now we have a .exe file with 89MB, instead of the one over 100MB.

With this .exe file, we can proceed to the release of our application.

Releasing WPF Application in VS App Center

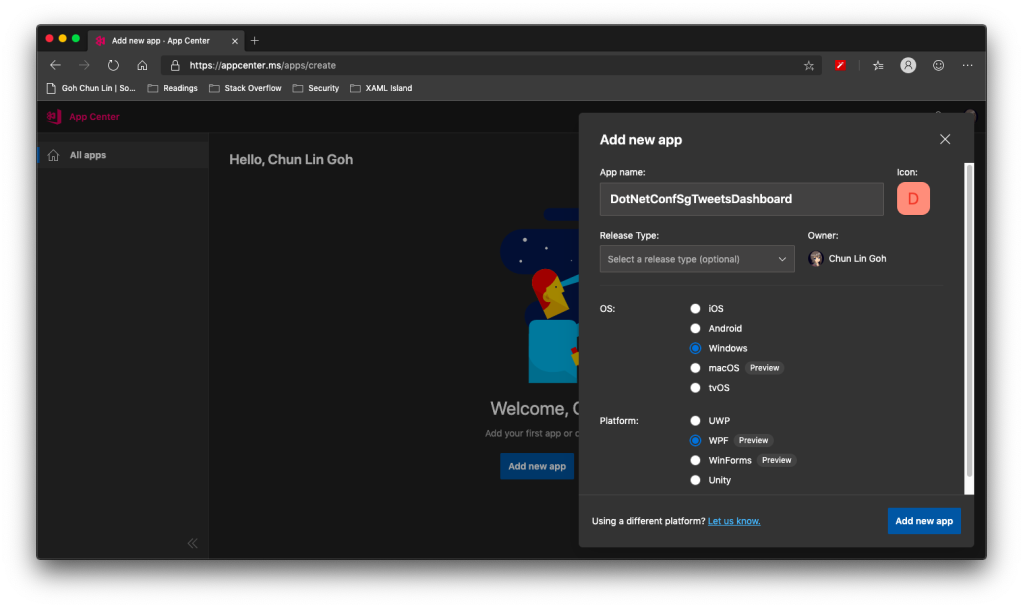

VS App Center was launched in 2017, which was previously known as VS Mobile Center. When it was first launched, it was mainly for Android, iOS, macOS, and Windows apps. The “Windows apps” here refer to UWP apps. Only in August 2019, WinForm and WPF applications are supported.

So, the artifact generated in Azure DevOps Build pipeline cannot be automatically delivered to VS App Center even after .NET Conf 2019. We now have to do it manually.

Firstly, we need to download the actifact as a zipped file in Azure DevOps.

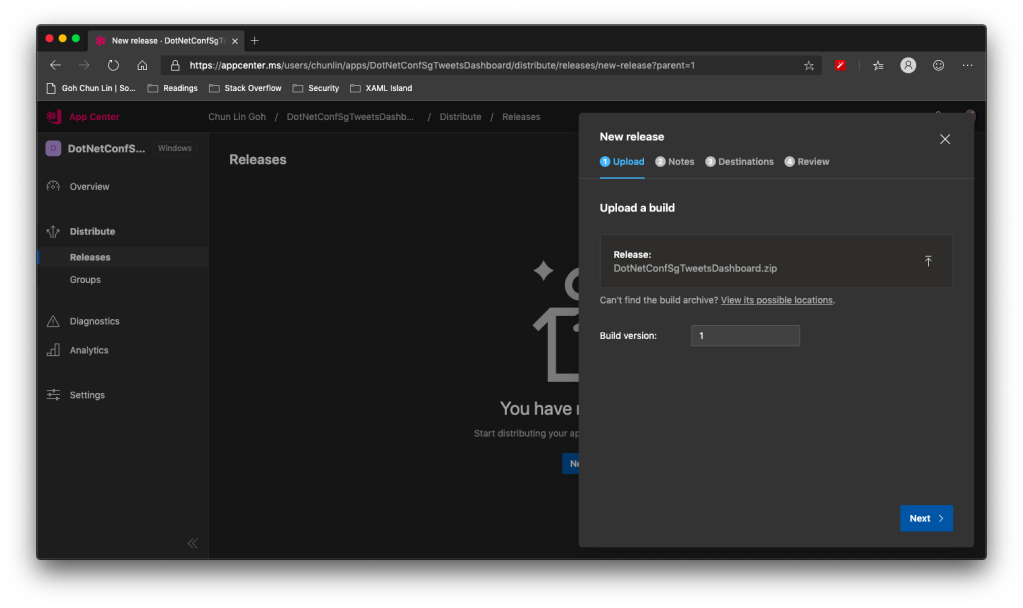

Secondly, we need to upload the zipped file to the VS App Center in its Releases tab, as shown in the following screenshot.

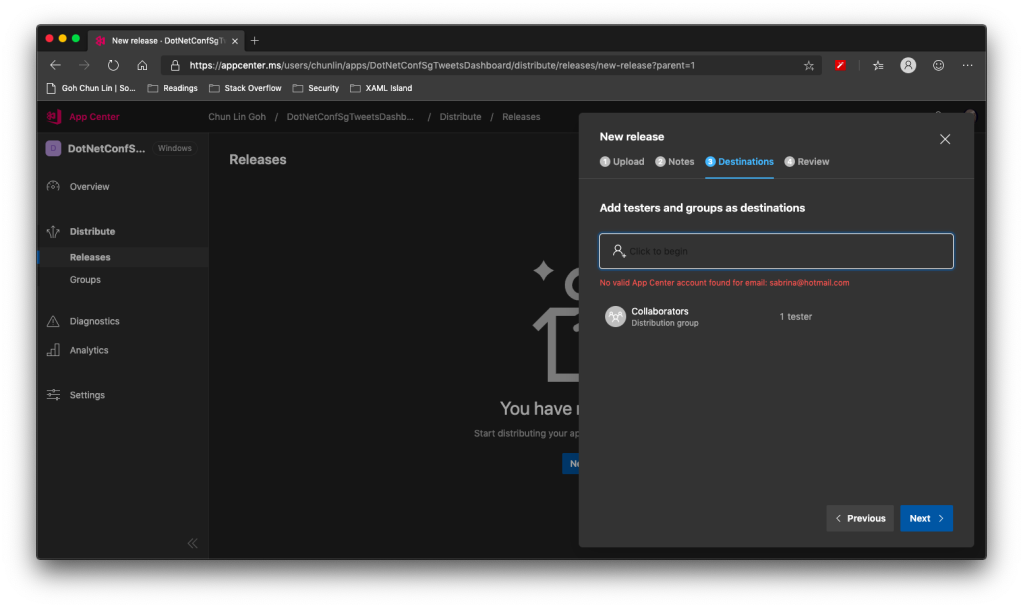

After keying the release notes, we will be landed on a page to choose who we should distribute the app to. Normally they are our developers, business analysts, and testers. Here, in my example, I only have one group called Collaborator and I am the only one in the group.

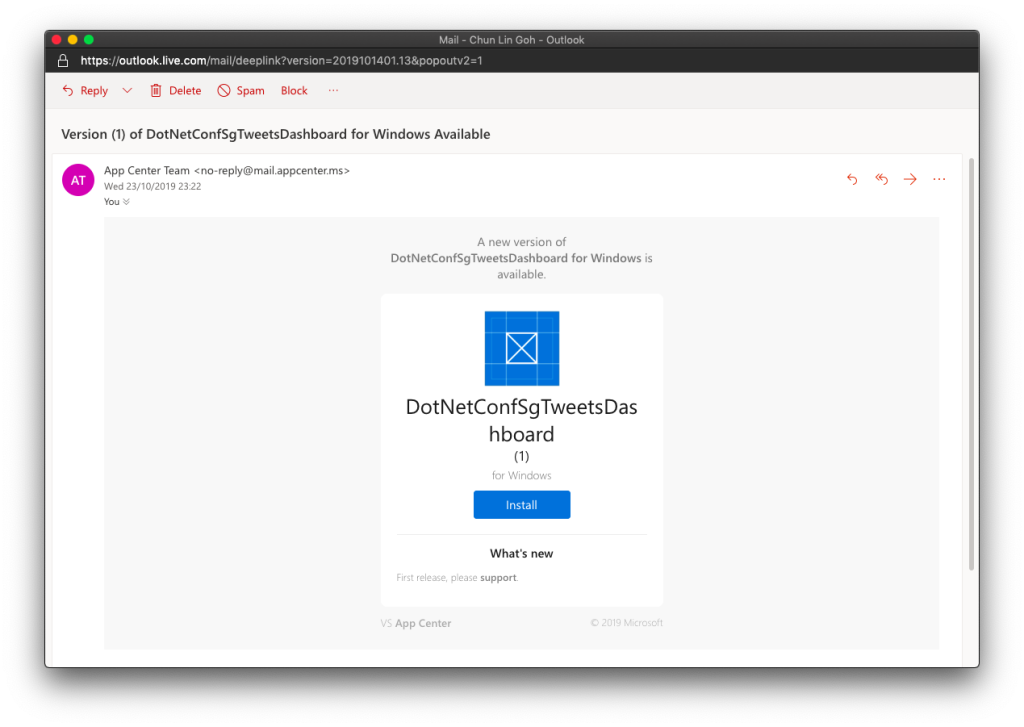

Finally, we will hit the “Distribute” button to release our app to testers. As tester, I will receive the email notifying about the new release.

Analytics with App Center SDK

We can also integrate our WPF desktop app with App Center SDK to further collect data to find out how people use our app as well as the crashes in our app.

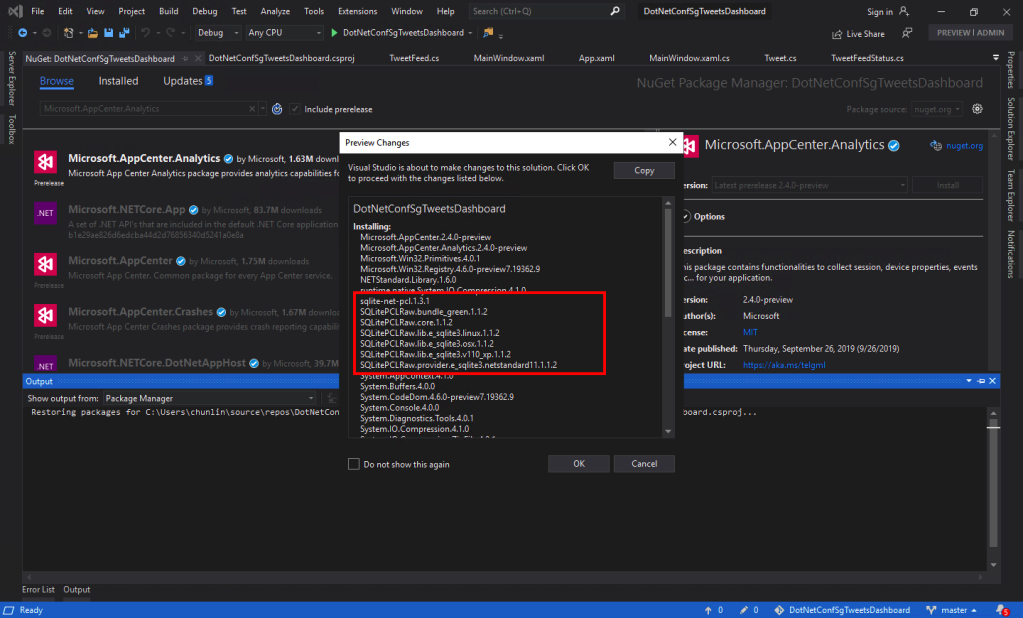

To do so, firstly, we need to install the following two Nuget packages. As the support for WPF SDK is still in preview, please remember to check the “Include prerelease” checkbox.

- Microsoft.AppCenter.Analytics;

- Microsoft.AppCenter.Crashes.

Now we can proceed to put the following code in the first window that will be launched in our app. In my case, it is the MainWindow. So, right after the InitializeComponent() is called, the following codes will be executed.

AppCenter.Start("<app-secret>",

typeof(Analytics), typeof(Crashes));

The App Secret can be found in the code sample of the Overview page in VS App Center.

However, if we run the WPF app now, the Analytics Overview page in VS App Center will still say there is no data. Why is it so?

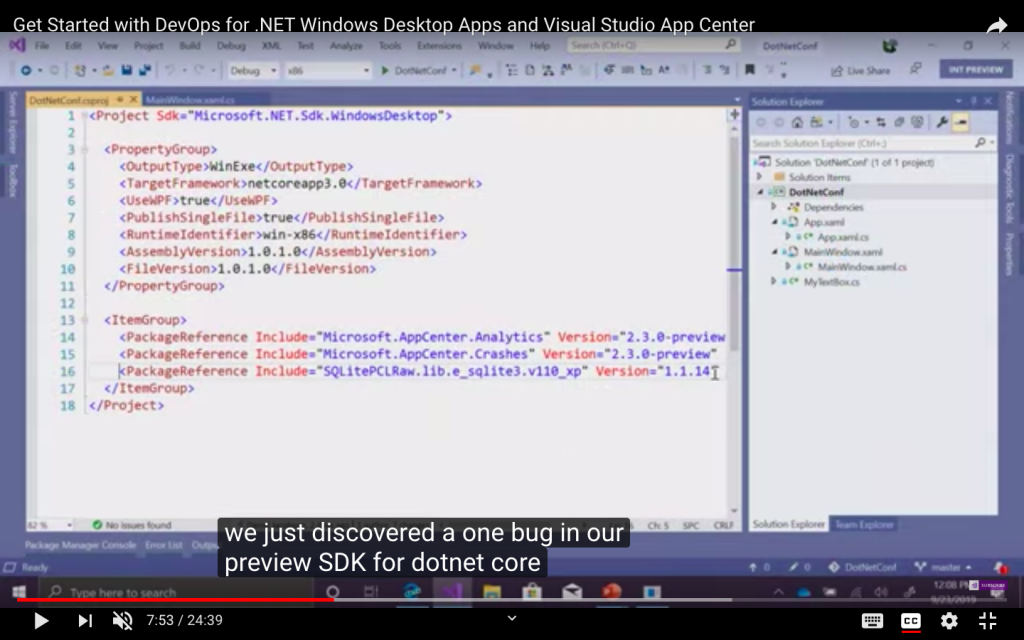

It turns out that, as highlighted in .NET Conf 2019, there is a bug in the preview SDK.

So what we need to do is simply to add the following line in <ItemGroup> in the .csproj file.

<PackageReference Include="SQLitePCLRaw.lib.e_sqlite3.v110_xp" Version="1.1.14" />

Yup, if you have noticed earlier when we’re installing the App Center SDK, SQLitePCLRaw was being installed also. Just because of the bug in the SDK, this line was not added to the project file and thus we have to manually reference it. Hopefully this bug gets fixed soon.

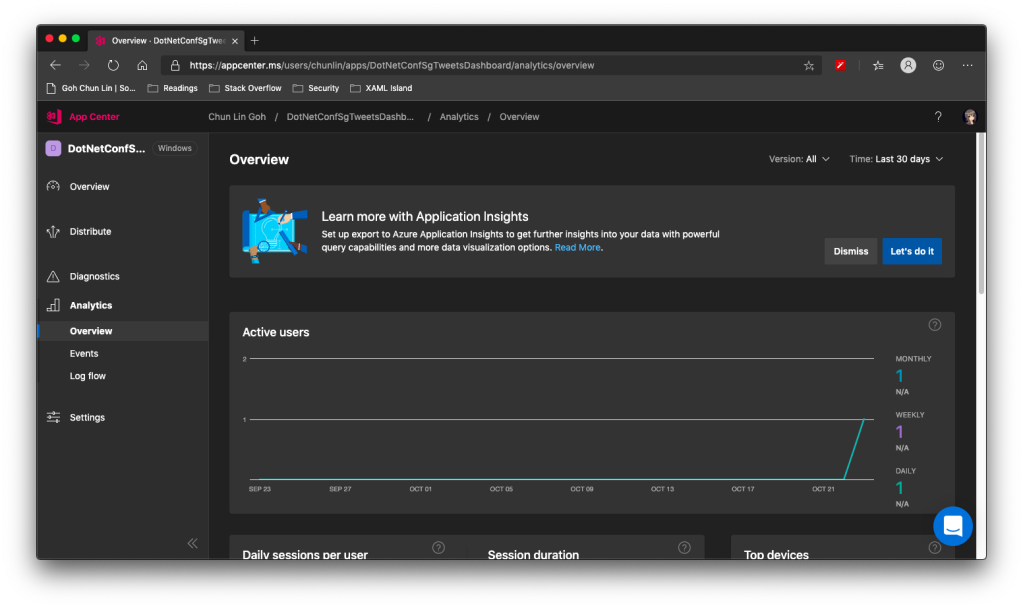

Now when we launch our WPF app again, the nice dashboard will show there is 1 user. Yay!

Conclusion

That’s all so far for what I’d like to share in addition to what I have shared in .NET Conf Singapore 2019.

If you spot any mistake or you have any suggestion to make, please let me know in the Comments section below. Thank you!

References

- Create a Trimmed Self-Contained Single Executable in .NET Core 3.0;

- Publishing A Single EXE File In .NET Core 3.0;

- The 3 .NET Conf 2019 videos mentioned above.