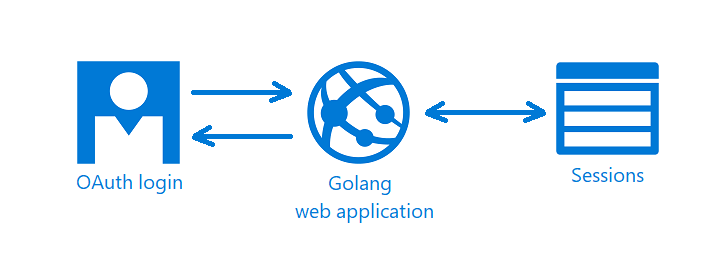

Continue from the previous topic…

Learning about containers is essentially a huge topic but for beginners, there needs to be something small to help them get started. Hence, in this article, we will focus only on the key concepts of containers and the steps to containerize the program and deploy it to Azure Web App.

In 2017, Azure introduced Web Apps for Containers. Before that, the Azure Web Apps actually ran on Windows VMs managed by Microsoft. So now with this new feature, we can build a custom Docker image containing all the binaries and files and then run a Docker container based on the image on Azure Web Apps. Hence, we can now bring our own Docker container images supporting Golang to Azure with its PaaS option.

As explained in the book “How to Containerize Your Go Code“, containers isolates an application so that container thinks it’s running on its own private machine. So, a container is similar to a VM but it uses the OS kernel on the host rather than having its own.

Firstly, we need to prepare the Dockerfile, a file having the instructions telling the Docker how to build the images automatically. So, a Dockerfile is simply a text file containing all the commands a user could call on the command line to assemble an image. Traditionally, the Dockerfile is named Dockerfile and located in the root of the context.

The Dockerfile we have for our project is as follows.

FROM scratch

EXPOSE 80

COPY GoLab /

COPY public public

COPY templates templates

ENV APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY '' \

CONNECTION_STRING '' \

OAUTH_CLIENT_ID '' \

OAUTH_CLIENT_SECRET '' \

COOKIE_STORE_SECRET '' \

OAUTH2_CALLBACK ''

CMD [ "/GoLab" ]

The Dockerfile starts with a FROM command that specifies the starting point for the image to build. For our project, we don’t have any dependencies, so we can start from scratch. So what is scratch? Scratch is basically a special Docker image that is empty (0B). That means there will be nothing else in our container later aside from what we put in with the rest of the Dockerfile.

The reason why we build from scratch is because not only we can have a smaller image to build later, but also our container will have smaller attack surface. This is because the less code there is within our container, the less likely it is to include a vulnerability.

The EXPOSE 80 command is telling Docker that we need to open the port 80 because the web server is listening on port 80. Hence, in order to access our program from outside the container through HTTP, we need to define it in the Dockerfile that we need the port 80 to be always opened.

The next three COPY commands are basically copying firstly the GoLab executable into the root directory of the container and secondly the two directories, public and templates into the container. Without the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, our web app will not work.

Now you may wonder why the first COPY command says GoLab instead of GoLab.exe. We shall discuss it later in this article.

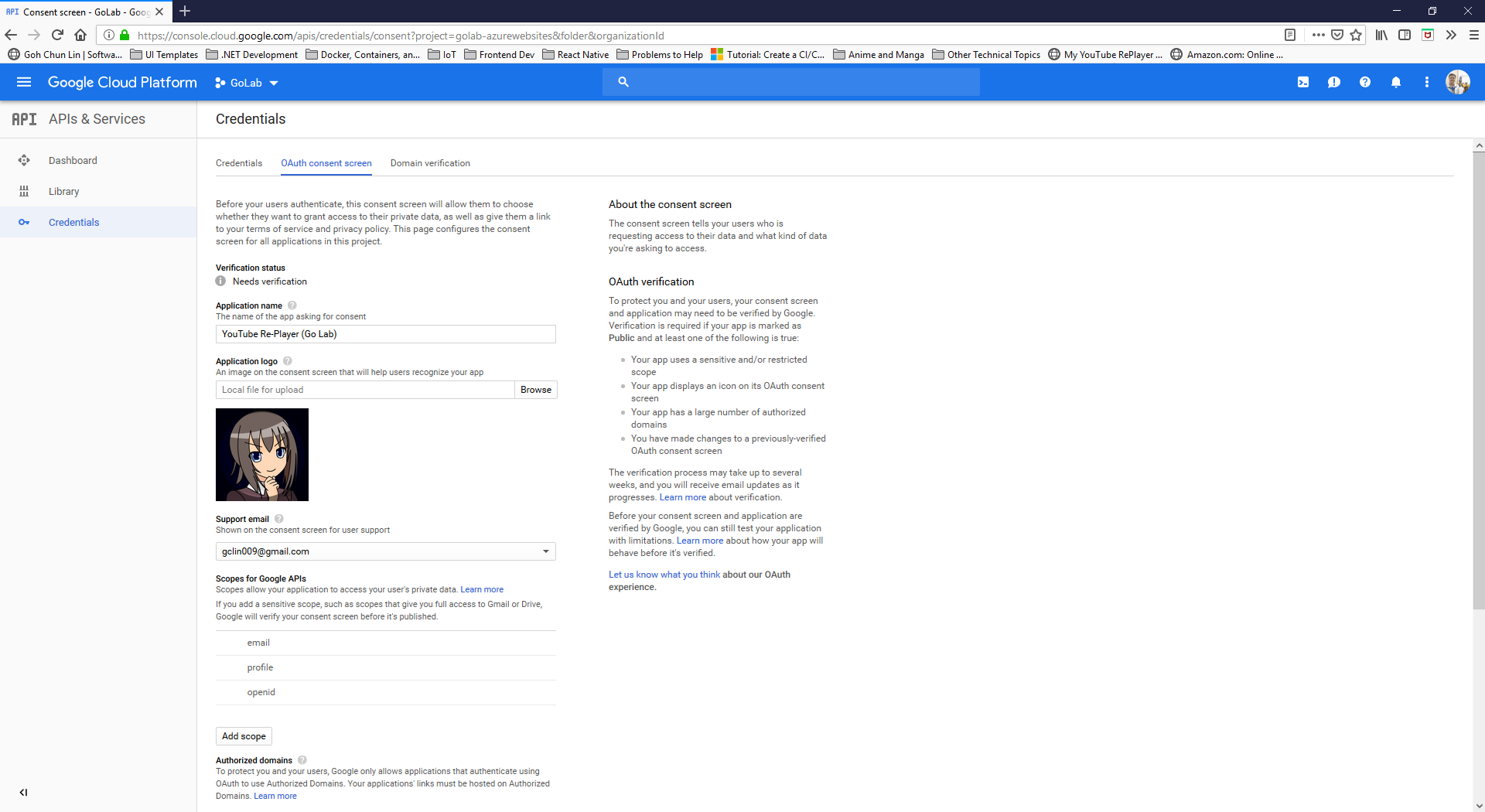

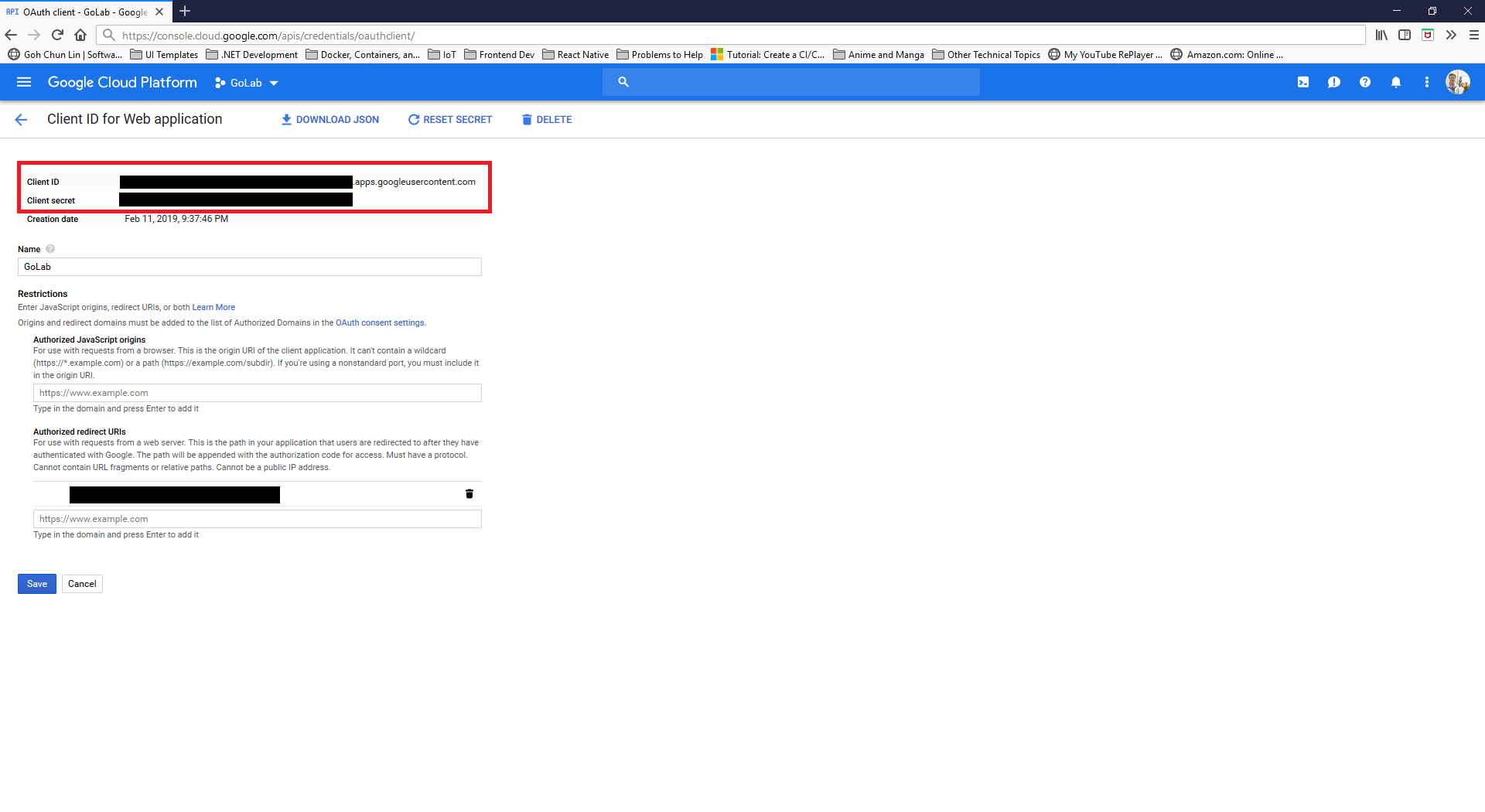

After that, we use ENV command to set the environment variables that we will be using in the app.

Finally we have the line CMD [“/GoLab”] to directs the container as to which command to execute when the container is run.

Since the container is not a Windows container, the code that runs inside the container thus needs to be a Linux binary. Fortunately, this is really simple to obtain with the cross-compilation support in Go using the following command.

$ $env:GOOS = "linux"

$ go build -o GoLab .

Thus, in the Dockerfile, we use GoLab file instead of GoLab.exe.

We can now proceed to build the container image with the following command (Take note of the dot in the end of line).

$ docker image build -t chunlindocker/golab:v1 .

The -t flag is for us to specify the name and tag of the container. In this case, I call it chunlindocker/golab:v1 where chunlindocker is the Docker ID of my Docker Hub. Naming in such a way later helps me to push it to a registry, i.e. the Docker Hub.

If we want to build the image with another dockerfile, for example Dockerfile.development, we can do it as follows.

$ docker image build -t chunlindocker/golab:v1 -f Dockerfile.development .

Once the docker image is built, we can see it listen when we perform the list command as shown in the screenshot below.

Now the container image is “deployable”. That means we can run it anywhere with a running docker engine. Since our laptop has Docker installed, so we can proceed to run it locally with the following command.

$ docker container run -P chunlindocker/golab:v1

If you run the command above in the Terminal window inside VS Code, you will see that the command line is “stuck”. This is because the container is already running on local machine. So what we need to do is just open another terminal window and view all the running containers.

To help humans, Docker auto generates a random name with two words and assigns it to the container. We can see that the container we created is given a random name “nifty_elgama”, lol. So now our container has a “human” name to call. If you want to remove the container later, you not only need to Ctrl+C to stop it, but to totally remove it, you need to use the rm command as follows.

$ docker container rm nifty_elgama

The PORTS column shown in the screenshot is important because it tells us how ports exposed on the container can be accessed from the host. So to test it locally, we shall visit http://localhost:32768.

So our next step is to upload it to a container registry so that later it can be pulled onto any machines, including Azure Web Apps, that will run it. To do so, we do push the image we built above to Docker Hub with the following command.

$ docker push chunlindocker/golab:v1

So, now how do we deploy the container to Azure?

Firstly, we need to create a Web App for Containers on the Azure Portal, as shown in the screenshot below.

The last item in the configuration is the “Configure Container”. Clicking on that, we will be brought to the following screen where we can then specify the container image we want to use and pull it from Docker Hub.

You can of course deploy a private container from Docker Hub by choosing “Private” as Repository Access. Then Azure Portal will prompt you for Docker Hub login credential for it to pull image from Docker Hub.

Once the App Service is created, we can proceed to read the Logs under “Container Settings”. Then we can see the container initializing process.

After that we can proceed to fill up the Application Settings with the environment variables we have in the web application and then we are good to go.