In order to build applications which utilise the scalability, flexibility, and resilience of cloud computing, the applications are nowadays normally developed with microservice architecture using containers. Microservice architecture enables our applications to be composed of small independent backend services that communicate with each other over the network.

Project GitHub Repository

The complete source code of this project can be found at https://github.com/goh-chunlin/Lunar.MicroFrontEnd.SingleSpa.

Why Micro Frontend?

In general, when applying a microservice architecture, while backend systems are split up into microservices, frontend is still often developed as a monolith. This is not a problem when our application is small and we have a strong frontend team working on its frontend. However when the application grows to a larger scale, a monolithic frontend will start to be inefficient and unmaintainable due to the following reasons.

Firstly, it is challenging to keep the frontend technologies used in a large application up-to-date. Hence, with micro frontend, we can upgrade the version of the frontend on a functional basis. It also allows developers to use different frontend technologies to different functions based on the needs.

Secondly, since the source code of the micro frontend is separated, the source code of the individual frontend component is not as much as the monolith version of it. This improves the maintainability of the frontend because smaller code is easy to understand and distribute.

Thirdly, with micro frontend, we can split the frontend development team into smaller teams so that each team only needs to focus on relevant business functions.

Introduction of single-spa

In micro frontend architecture, we need a framework to bring together muliple JavaScript micro frotnends in our application. The framework we’re going to discuss here is called the single-spa.

The reason why we choose single-spa is because it is a framework allowing the implementation of micro frontend by supporting many popular JavaScript UI frameworks such as Angular and Vue. By leveraging the single-spa framework, we are able to register micro frontends such that the micro frontends are mounted and unmounted correctly for different URLs.

In this article, single-spa will work as an orchestrator to handle the micro frontend switch so that individual micro frontend does not need to worry about the global routing.

The Orchestrator

The orchestrator is nothing but a project holding single-spa which is responsible for global routing, i.e. determining which micro frontends get loaded.

Fortunately, there is a very convenient way for us to get started quickly, i.e. using the create-single-spa, a utility for generating starter code. This guide will cover creating the root-config and our first single-spa application.

We can install the create-single-spa tool globally with the following command.

npm install --global create-single-spa

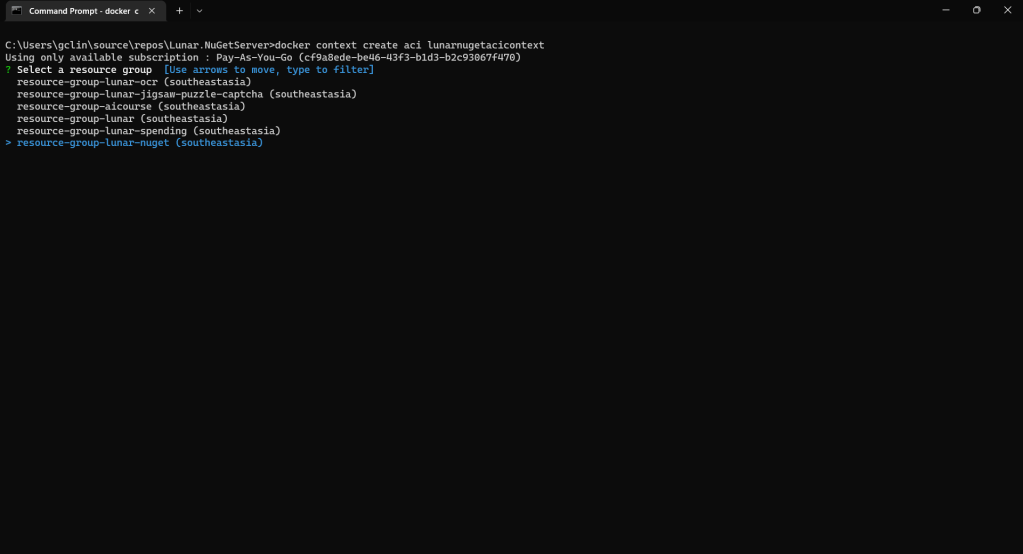

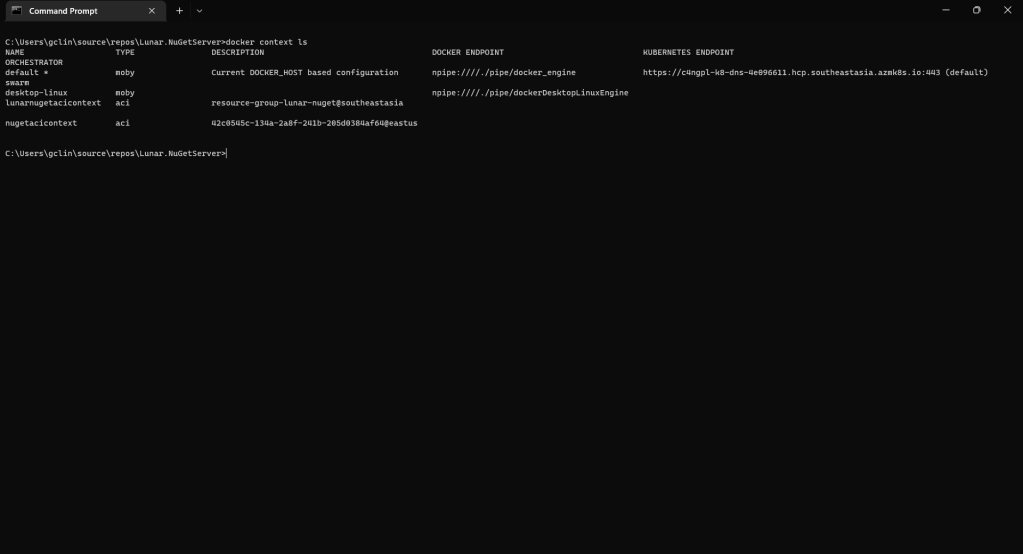

Once it is installed, we will create our project folder containing another empty called “orchestrator”, as shown in the following screenshot.

We will now create the single-spa root config, which is the core of our orchestrator, with the following command.

create-single-spa

Then we will need to answer a few questions, as shown in the screenshots below in order to generate our orchestrator.

That’s all for now for our orchestrator. We will come back to it after we have created our micro frontends.

Micro Frontends

We will again use the create-single-spa to create the micro frontends. Instead of choosing root config as the type, this time we will choose to generate the parcel instead, as shown in the following screenshot.

To have our orchestrator import the micro frontends, the micro frontend app needs to be exposed as a System.register module, as shown below on how we edit the vue.config.js file with the following configuration.

const { defineConfig } = require('@vue/cli-service')

module.exports = defineConfig({

transpileDependencies: true,

configureWebpack: {

output: {

libraryTarget: "system",

filename: "js/app.js"

}

}

})

Now, we can proceed to build this app with the following command so that the app.js file can be generated.

npm run build

We then can serve this micro frontend app with http-server for local testing later. We will be running the following command in its dist directory to specify that we’re using port 8011 for the app1 micro frontend.

http-server . --port 8011 --cors

Link Orchestrator with Micro Frontend AppS

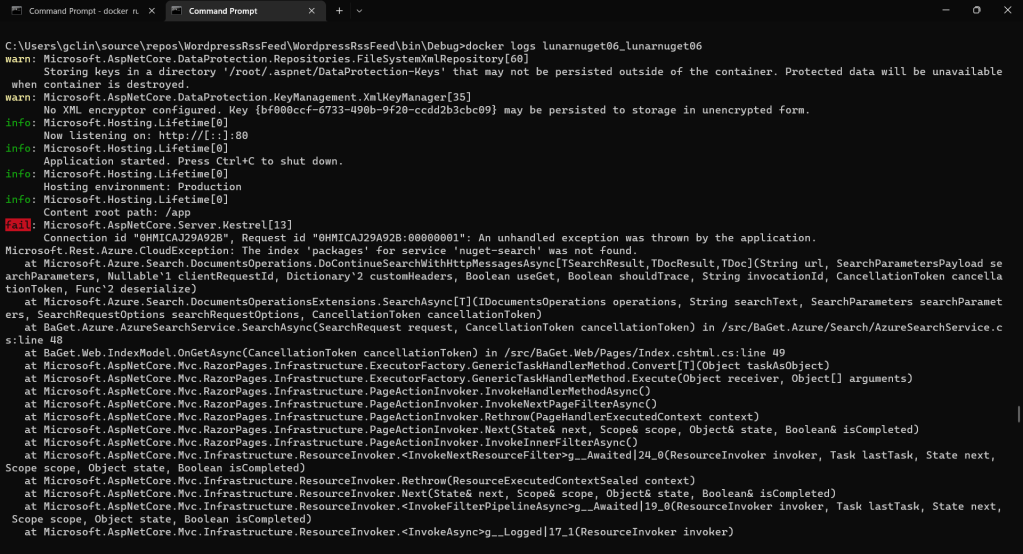

Now, we can return to the index.ejs file to specify the URL of our micro frontend app as shown in the screenshot below.

Next, we need to define the place where we will display our micro frontend apps in the microfrontend-layout.js, as shown in the screenshot below.

<single-spa-router>

<main>

<route default>

<div style="display: grid; column-gap: 50px; grid-template-columns: 30% auto; background-color: #2196F3; padding: 10px;">

<div style="background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.8); padding: 20px;">

<application name="@Lunar/app1"></application>

</div>

<div>

</div>

</div>

</route>

</main>

</single-spa-router>

We can now launch our orchestrator with the following command in the orchestrator directory.

npm start

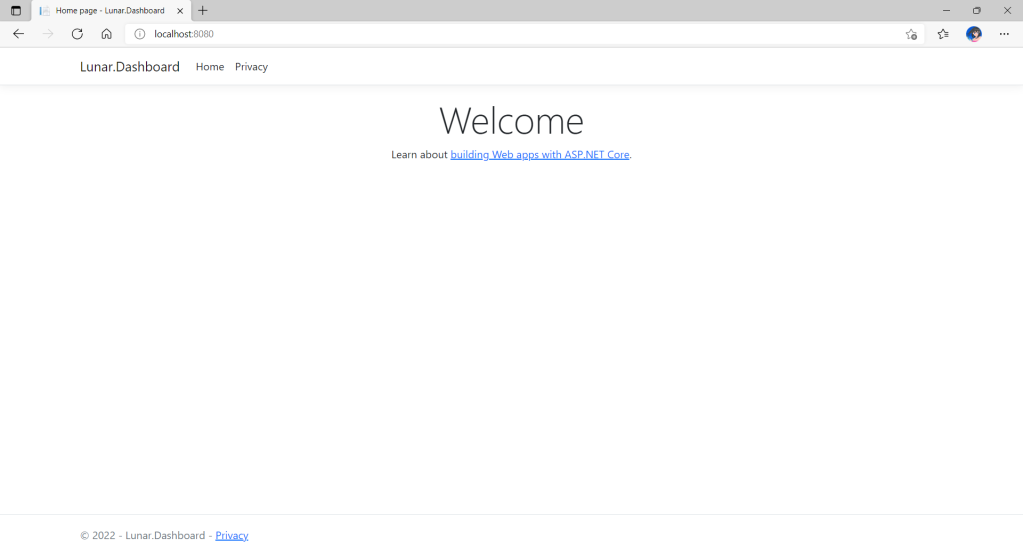

Now, if we repeat what we have done for app1 for another Vue 3.0 app called app2 (which we will deploy on port 8012), we can achieve something as follows.

Finally, to have the images shown properly, we simply need to update the Content-Security-Policy to be as follows.

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'self' https: localhost:*; img-src data:; script-src 'unsafe-inline' 'unsafe-eval' https: localhost:*; connect-src https: localhost:* ws://localhost:*; style-src 'unsafe-inline' https:; object-src 'none';">

Also, in order to make sure the orchestrator indeed loads two different micro frontends, we can edit the content of the two apps to look different, as shown below.

Design System

In a micro frontend architecture, every team builds its part of the frontend. With this drastic expansion of the frontend development work, there is a need for us to streamline the design work by having a complete set of frontend UI design standards.

In addition, in order to maintain the consistency of the look-and-feel of our application, it is important to make sure that all our relevant micro frontends are adopting the same design system which also enables developers to replicate designs quickly by utilising premade UI components.

Here in single-spa, we can host our CSS in one of the shared micro frontend app and then have it contains only the common CSS.

Closing

In 2016, Thoughtworks introduced the idea of micro frontend. Since then, the term micro frontend has been hyped.

However, micro frontend is not suitable for all projects, especially when the development team is small or when the project is just starting off. Micro frontend is only recommended when the backend is already on microservices and the team finds that scaling is getting more and more challenging. Hence, please plan carefully before migrating to micro frontend.

If you’d like to find out more about the single-spa framework that we are using in this article, please visit the following useful links.