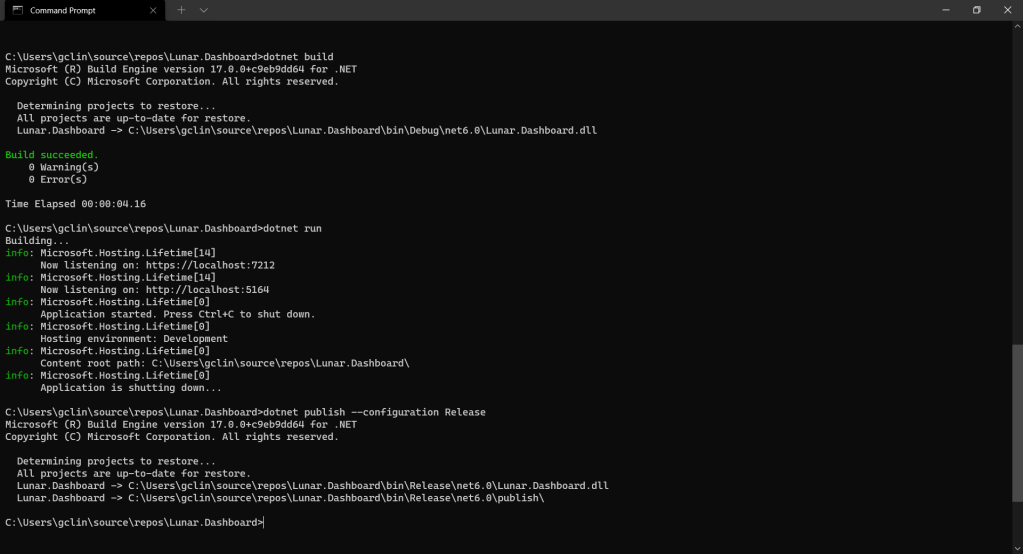

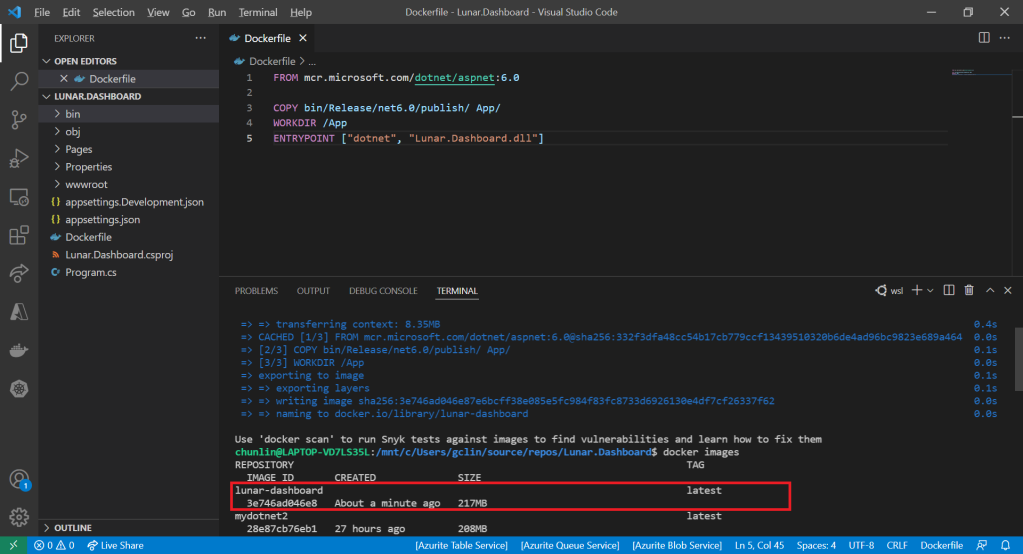

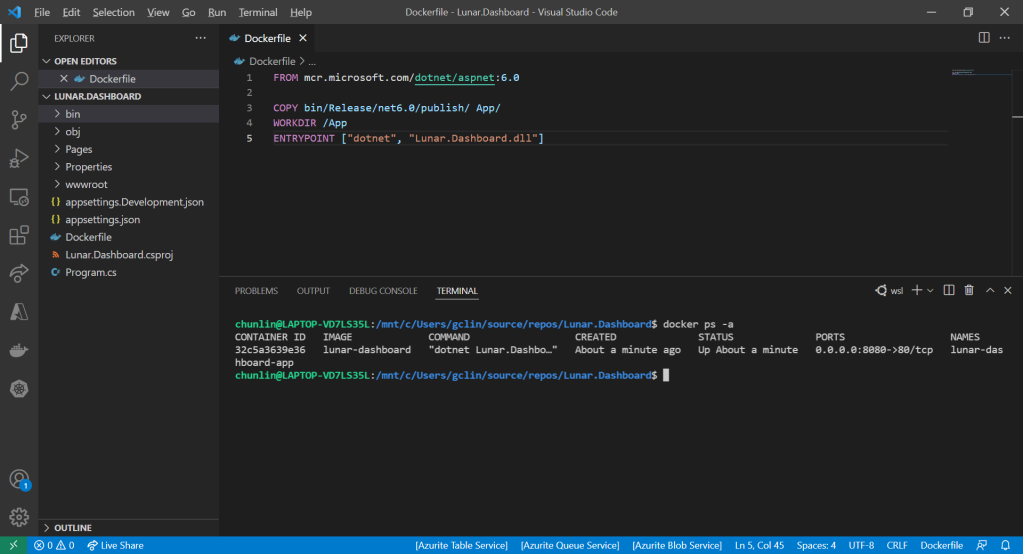

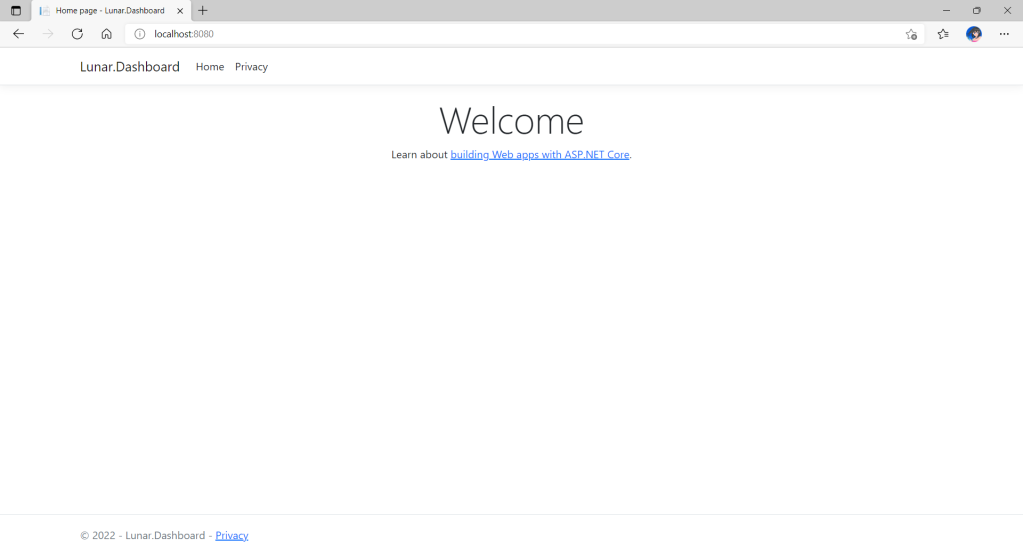

Previously, we have seen how we could containerise our ASP .NET Core 6.0 web app and manage it with docker commands. However, docker commands are mainly for only one image/container. If our solution has multiple containers, we need to use docker-compose to manage them instead.

docker-compose makes things easier because it encompasses all our parameters and workflow into a configuration file in YAML. In this article, I will share my first experience with docker-compose to build mutli-container environments as well as to manage them with simple docker-compose commands.

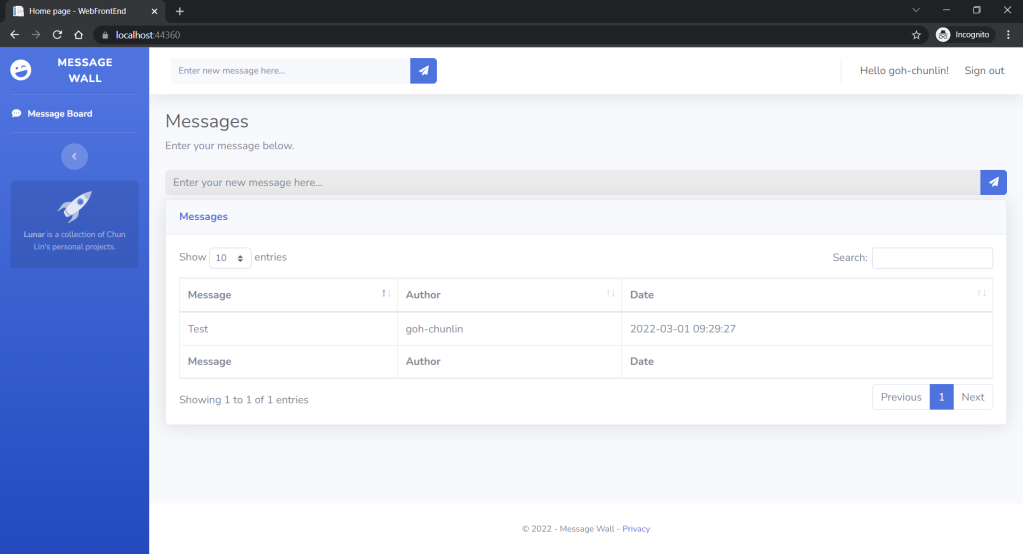

To help my learning, I will create a simple online message board where people can login with their GitHub account and post a message on the app.

PROJECT GITHUB REPOSITORY

The complete source code of this project can be found at https://github.com/goh-chunlin/Lunar.MessageWall.

Create Multi-container App

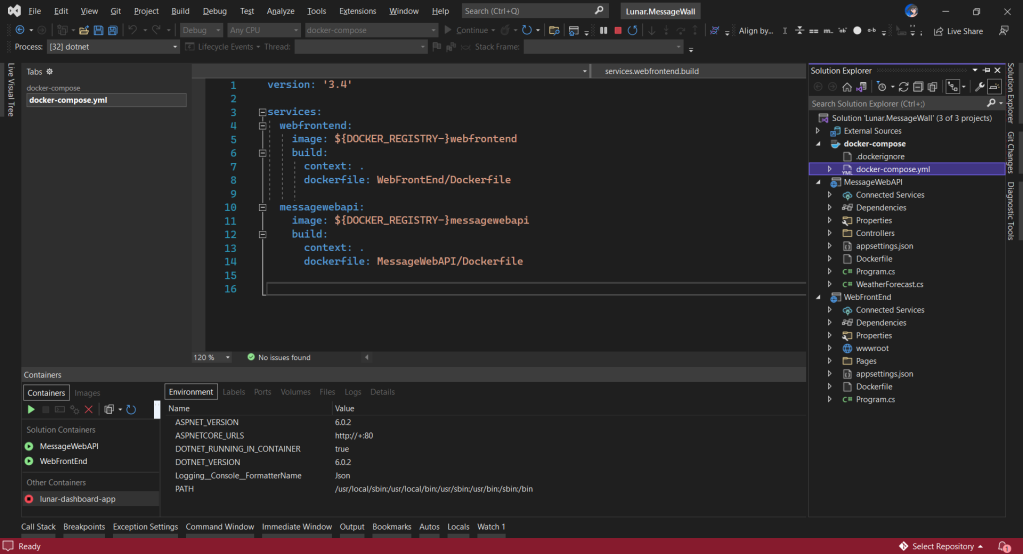

We will start with a solution in Visual Studio with two projects:

- WebFrontEnd: A public-facing web application with Razor pages;

- MessageWebAPI: A web API project.

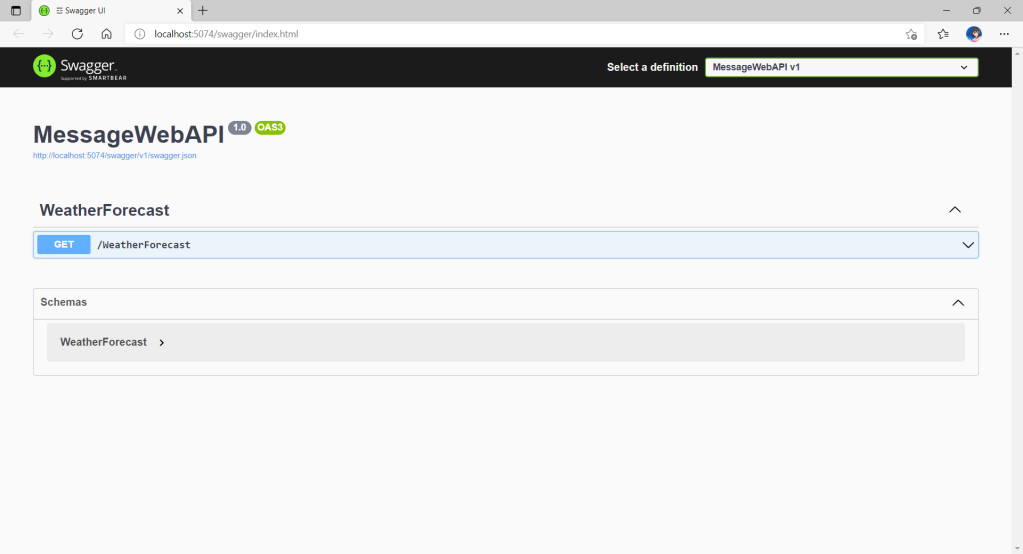

By default, the web API project will have a simple GET method available, as shown in the Swagger UI below.

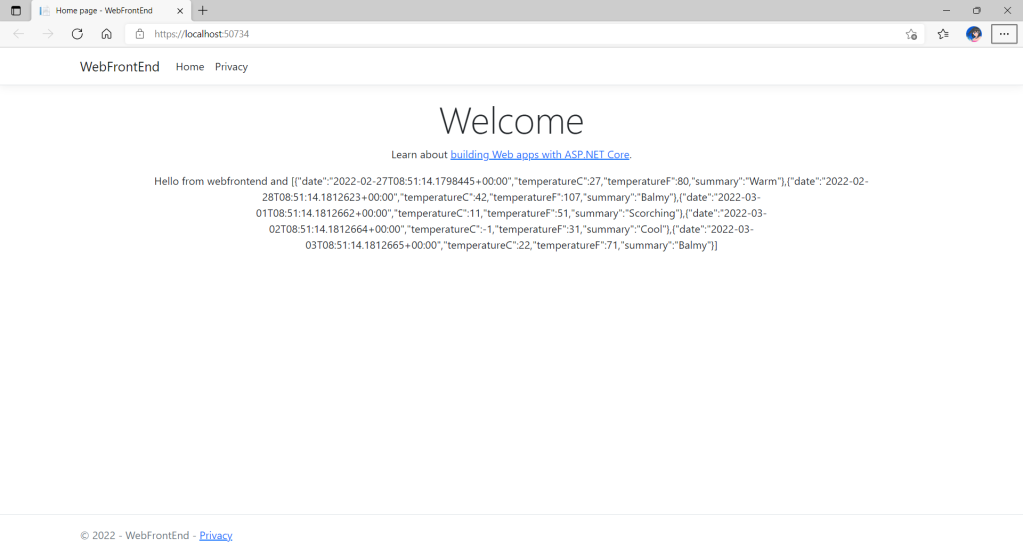

Now, we can make use of this method as a starting point. Let’s have the our client, WebFrontEnd, to call the API and output the result returned by the API to the web page.

var request = new System.Net.Http.HttpRequestMessage();

request.RequestUri = new Uri("http://messagewebapi/WeatherForecast");

var response = await client.SendAsync(request);

string output = await response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync();

In both projects, we will add Container Orchestrator Support with Linux as the target OS. Once we have the docker-compose YAML file ready, we can directly run our docker compose application by simply pressing F5 in Visual Studio.

Now, we shall be able to see the website output some random weather data returned by the web API.

Configure Authentication in Web App

Our next step is to allow users to login to our web app first before they can post a message on the app.

It’s usually a good idea not to build our own identity management module because we need to deal with a lot more than just building a form to allow users to create an account and type their credentials. One example will be managing and protecting our user’s personal data and passwords. Instead, we should rely on Identity-as-a-Service solutions such as Azure Active Directory B2C.

Firstly, we will register our web app in our Azure AD B2C tenant.

Normally for first-timers, we will need to create a Azure AD B2C tenant first. However, there may be an error message saying that our subscription is not registered to use namespace ‘Microsoft.AzureActiveDirectory’. If you encounter this issue, you can refer to Adam Storr’s article on how to solve this with Azure CLI.

Once we have our Azure AD B2C tenant ready (which is Lunar in my example here), we can proceed to register our web app, as shown below. For testing purposes, we set the Redirect URI to https://jwt.ms, a Microsoft-owned web application that displays the decoded contents of a token. We will update this Redirect URL in the next section below when we link our web app with Azure AD B2C.

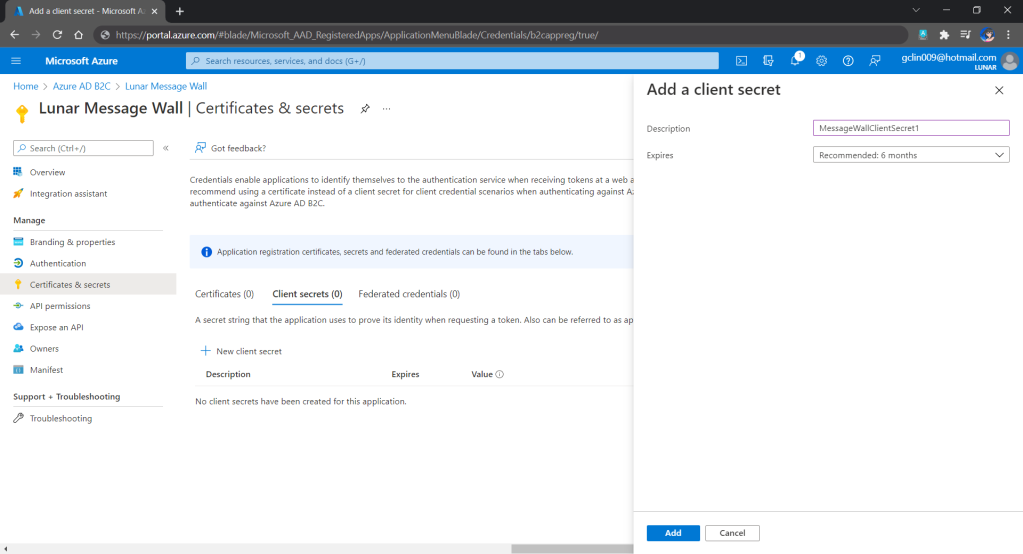

Secondly, once our web app is registered, we need to create a client secret, as shown below, for later use.

Secrets enable our web app to identify itself to the authentication service when receiving tokens. In addition, please take note that although certificate is recommended over client secret, currently certificates cannot be used to authenticate against Azure AD B2C.

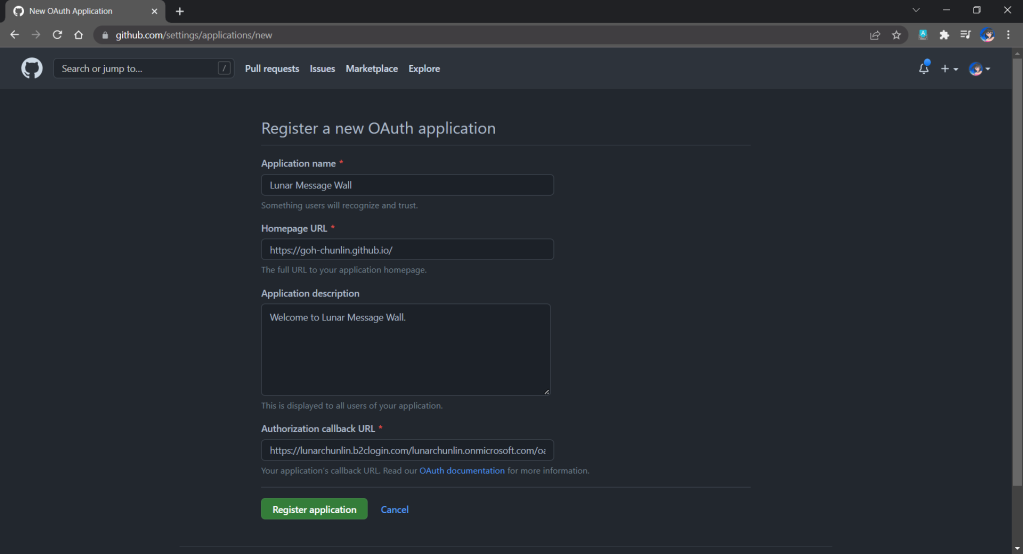

Thirdly, since we want to allow user authentication with GitHub, we need to create a GitHub OAuth app first.

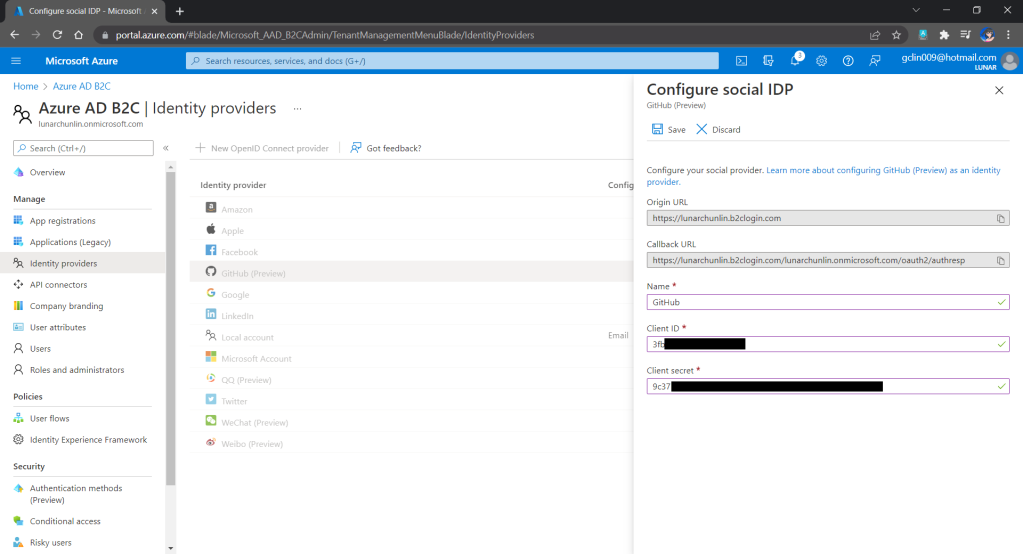

After we have registered the OAuth app on GitHub, we will be provided a client ID and client secret. These two information are needed when we configure GitHub as the social identity provider (IDP) on our Azure AD B2C, as shown below.

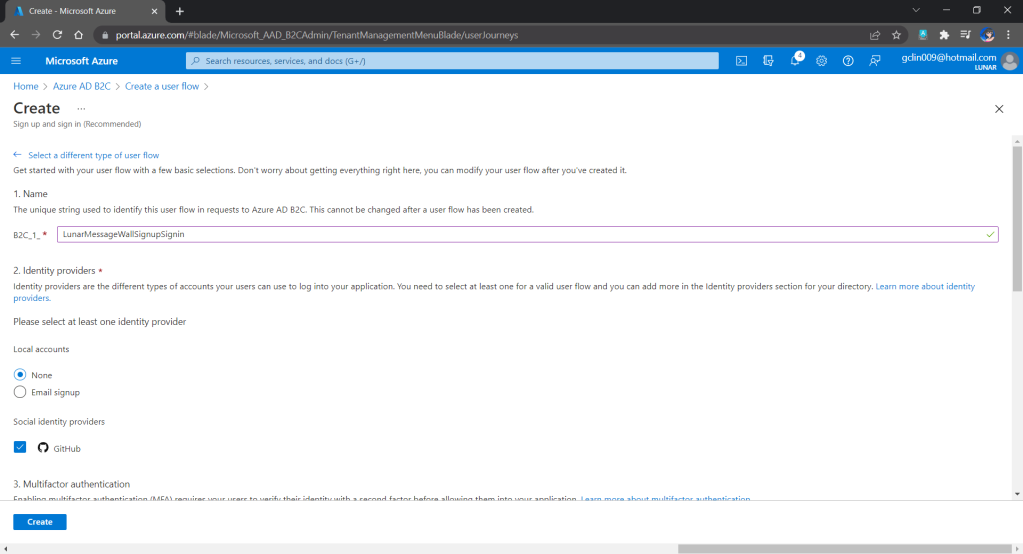

Fourthly, we need to define how users interact with our web app for processes such as sign-up, sign-in, password reset, profile editing, etc. To keep thing simple, here we will be using the predefined user flows.

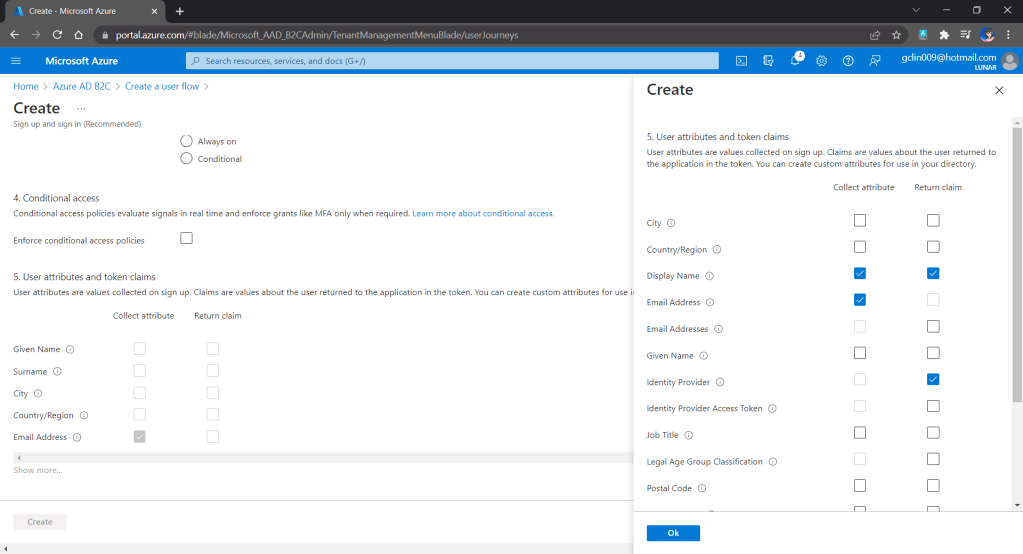

We can also choose the attributes we want to collect from the user during sign-up and the claims we want returned in the token.

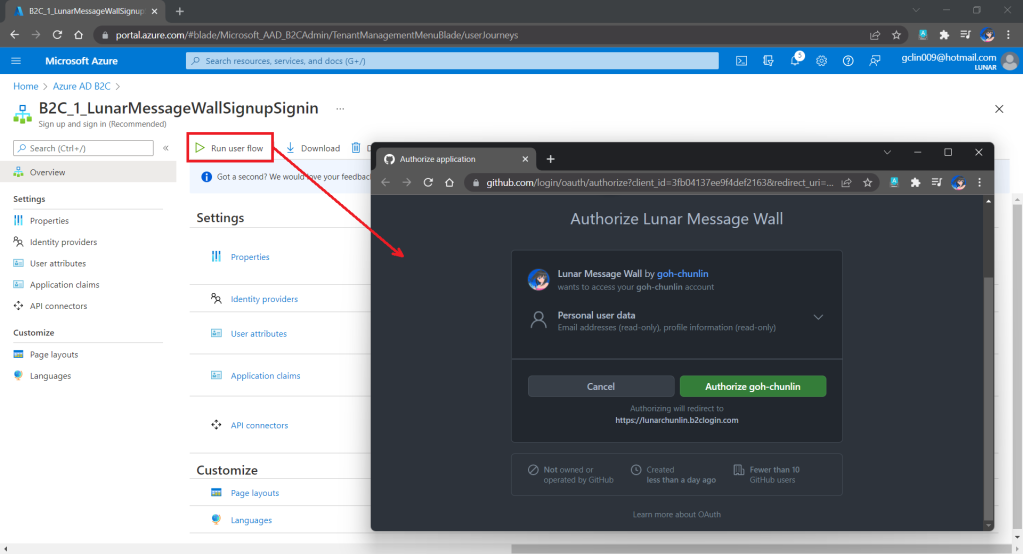

After we have created the user flow, we can proceed to test it.

Since we specify in our user flow that we need to collect the user’s GitHub display name, there is a field here for the user to enter the display name.

Setup the Authentication in Frontend and Web API Projects

Now, we can proceed to add Azure AD B2C authentication to our two ASP.NET Core projects.

We will be using the Microsoft Identity Web library, a set of ASP.NET Core libraries that simplify adding Azure AD B2C authentication and authorization support to our web apps.

dotnet add package Microsoft.Identity.Web

The library configures the authentication pipeline with cookie-based authentication. It takes care of sending and receiving HTTP authentication messages, token validation, claims extraction, etc.

For the frontend project, we will be using the following package to add GUI for the sign-in and an associated controller for web app.

dotnet add package Microsoft.Identity.Web.UI

After this, we need to add the configuration to sign in user with Azure AD B2C in our appsettings.json in both projects (The ClientSecret is not needed for the Web API project).

"AzureAdB2C": {

"Instance": "https://lunarchunlin.b2clogin.com",

"ClientId": "...",

"ClientSecret": "...",

"Domain": "lunarchunlin.onmicrosoft.com",

"SignedOutCallbackPath": "/signout/B2C_1_LunarMessageWallSignupSignin",

"SignUpSignInPolicyId": "B2C_1_LunarMessageWallSignupSignin"

}

We will use the configuration above to add the authentication service in Program.cs of both projects.

With the help of the Microsoft.Identity.Web.UI library, we can also easily build a sign-in button with the following code. Full code of it can be seen at _LoginPartial.cshtml.

<a class="nav-link text-dark" asp-area="MicrosoftIdentity" asp-controller="Account" asp-action="SignIn">Sign in</a>

Now, it is time to update the Redirect URI to the localhost. Thus, we need to make sure our WebFrontEnd container has a permanent host port. To do so, we first specify the ports we want to use in the launchsettings.json of the WebFrontEnd project.

"Docker": {

...

"environmentVariables": {

"ASPNETCORE_URLS": "https://+:443;http://+:80",

"ASPNETCORE_HTTPS_PORT": "44360"

},

"httpPort": 51803,

"sslPort": 44360

}

Then in the docker-compose, we will specify the same ports too.

services:

webfrontend:

image: ${DOCKER_REGISTRY-}webfrontend

build:

context: .

dockerfile: WebFrontEnd/Dockerfile

ports:

- "51803:80"

- "44360:443"

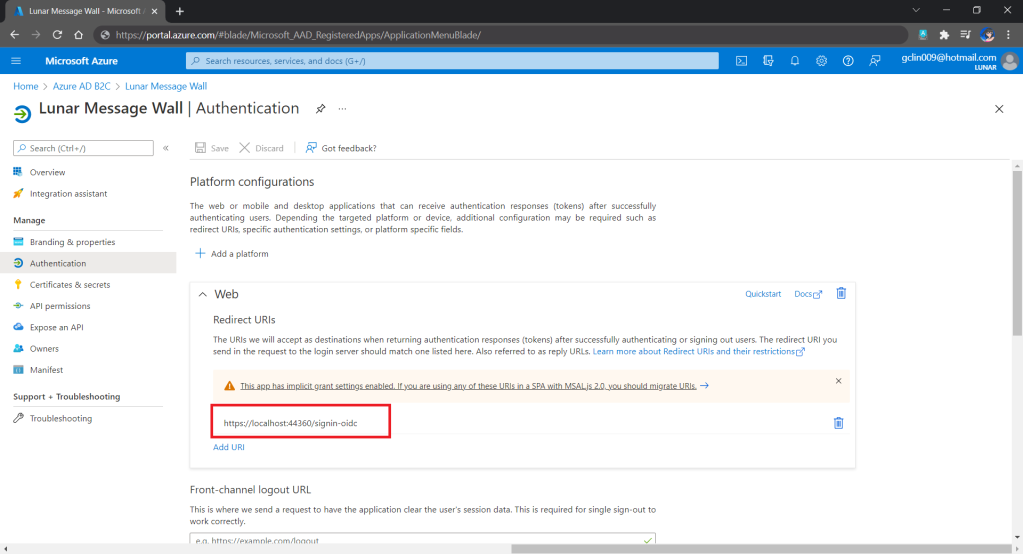

Finally, we will update the Redirect URI in Azure AD B2C according, as shown below.

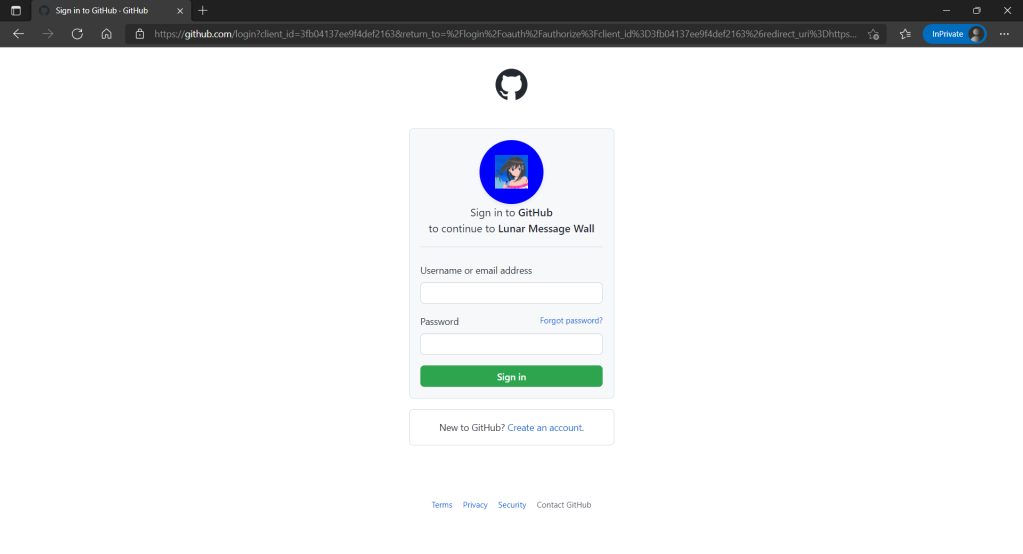

Now, right after we click on the Sign In button on our web app, we will be brought to a GitHub sign-in page, as shown below.

Currently, our Web API has only two methods which have different required scopes declared, as shown below.

[Authorize]

public class UserMessageController : ControllerBase

{

...

[HttpGet]

[RequiredScope("messages.read")]

public async Task<IEnumerable<UserMessage>> GetAsync()

{

...

}

[HttpPost]

[RequiredScope("messages.write")]

public async Task<IEnumerable<UserMessage>> PostAsync(...)

{

...

}

}

Hence, when the frontend needs to send the GET request to retrieve messages, we will first need to get a valid access token with the correct scope.

string accessToken = await _tokenAcquisition.GetAccessTokenForUserAsync(new[] { "https://lunarchunlin.onmicrosoft.com/message-api/messages.read" });

client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Authorization = new AuthenticationHeaderValue("Bearer", accessToken);

client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Accept.Add(new MediaTypeWithQualityHeaderValue("application/json"));

Database

Since we need to store the messages submitted by the users, we will need a database. Here, we use PostgresSQL, an open-source, standards-compliant, and object-relational database.

To run the PostgresSQL with docker-compose we will update our docker-compose.yml file with the following contents.

services:

...

messagewebapi:

...

depends_on:

- db

db:

container_name: 'postgres'

image: postgres

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: ...

In our case, only the Web API will interact with the database. Hence, we need to make sure that the db service is started before the messagewebapi. In order to specify this relationship, we will use the depends_on option.

Next Step

This is just the very beginning of my learning journey of dockerising ASP .NET Core solution. In the future, I shall learn more in this area.

References

- [YouTube] .NET Microservices – Full Course for Beginners;

- Create an Azure Active Directory B2C tenant;

- Subscription is not registered to use namespace Microsoft.AzureActiveDirectory;

- Code samples migrated to the new minimal hosting model in ASP.NET Core 6.0;

- What defines ASP.NET and ASP.NET Core APIs as protected?

- ASP.NET Core 6 and Authentication Servers;

- ASP.NET Core Implementation (Web Apps + SSO);

- Web app that signs in users: Code configuration;

- Configure authentication in a sample web app that calls a web API by using Azure AD B2C;

- Enable authentication in web apps that call a web API by using Azure AD B2C;

- Enable authentication in your own web API by using Azure AD B2C;

- [GitHub] How to secure a Web API built with ASP.NET Core using the Azure AD B2C;

- Options pattern in ASP.NET Core;

- Quickstart: Compose and ASP.NET Core with SQL Server;

- Dockerizing an ASP.NET Core Web API App and SQL Server;

- [GitHub] ASP.NET Core with PostgreSQL and Docker Demo;

- Postgres with Docker and Docker compose a step-by-step guide for beginners;

- Networking in Compose;

- Npgsql Entity Framework Core Provider;

- EF Core Migrations Overview;

- Seeding data using EF Core in ASP.NET Core 6.0 Minimal API;

- Using Forms in Razor Pages.