In a .NET Web API project, when we have to perform data processing tasks in the background, such as processing queued jobs, updating records, or sending notifications, it’s likely designed to concurrently perform database operations using Entity Framework (EF) in a BackgroundService when the project starts in order to significantly reduce the overall time required for processing.

However, by design, EF Core does not support multiple parallel operations being run on the same DbContext instance. So, we need to approach such background data processing tasks in a different manners as discussed below.

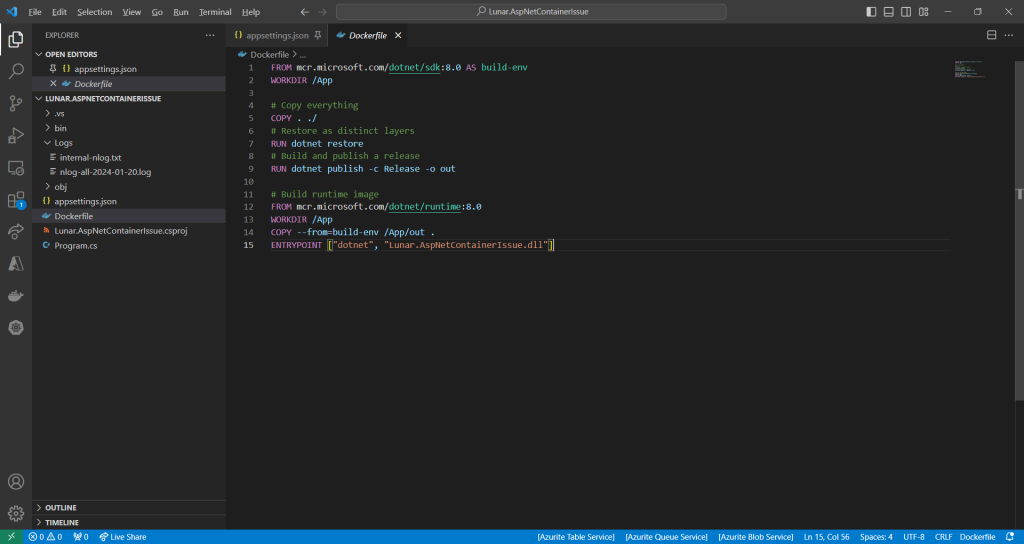

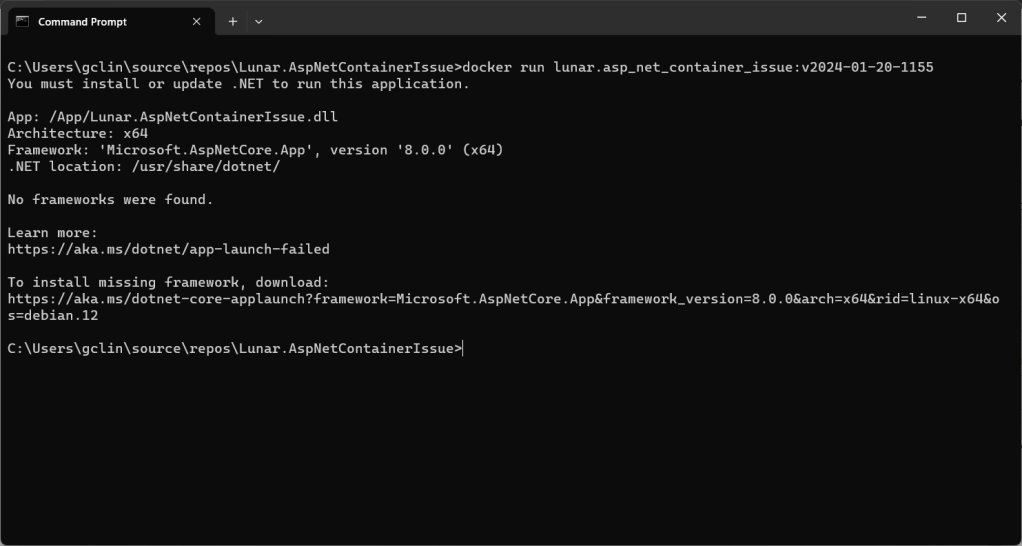

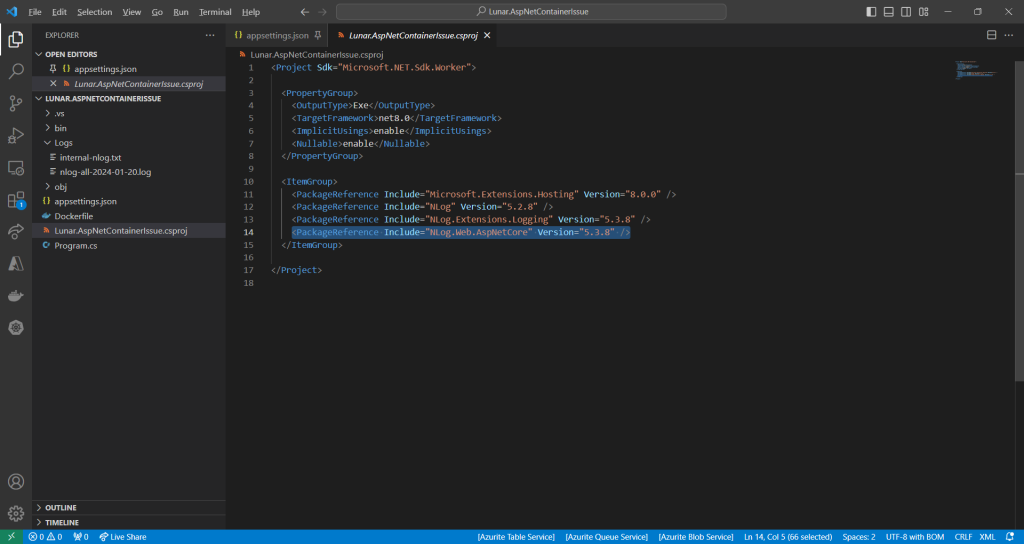

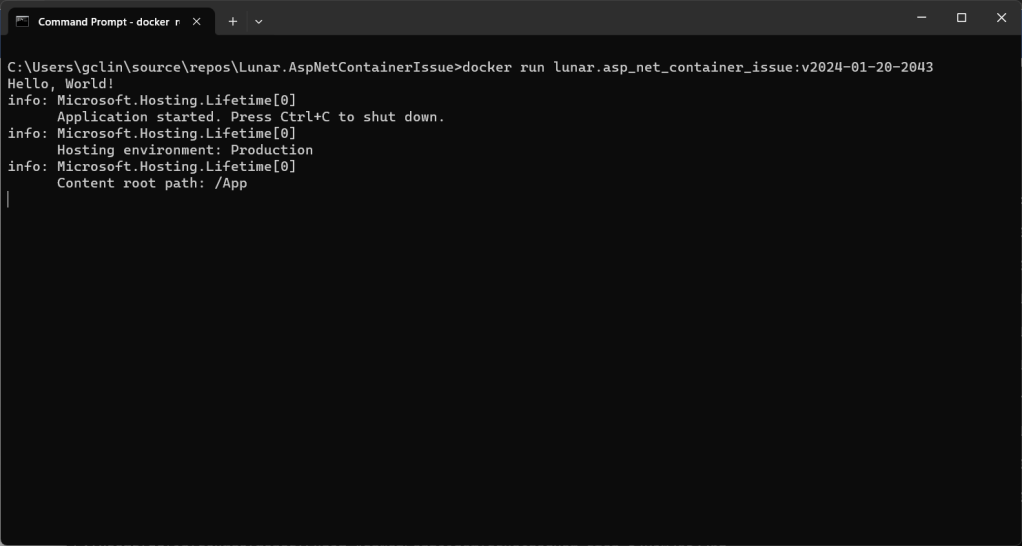

Code Setup

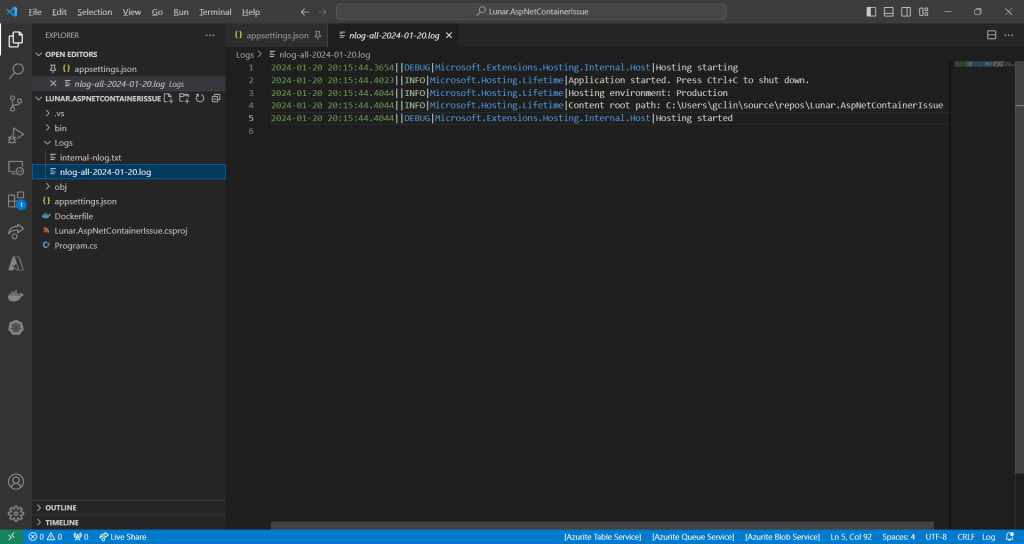

Let’s begin with a simple demo project setup.

In many ASP.NET Core applications, DbContext is registered with the Dependency Injection (DI) container, typically with a scoped lifetime. For example, in Program.cs, we can configure MyDbContext to connect to a MySQL database with .

builder.Services.AddDbContext<MyDbContext>(options =>

options.UseMySql(connectionString));

Next, we have a scoped service defined as follows. It will retrieve a set of relevant records from the database MyTable.

public class MyService : IMyService

{

private readonly MyDbContext _myDbContext;

public MyService(MyDbContext myDbContext)

{

_myDbContext = myDbContext;

}

public async Task RunAsync(CancellationToken cToken)

{

var result = await _myDbContext.MyTable

.Where(...)

.ToListAsync();

...

}

}

Here we will be consuming this MyService in a background task. In Program.cs, using the code below, we setup a background service called MyProcessor with the DI container as a hosted service.

builder.Services.AddHostedService<Processor>();

Hosted services are background services that run alongside the main web application and are managed by the ASP.NET Core runtime. A hosted service in ASP.NET Core is a class that implements the IHostedService interface, for example BackgroundService, the base class for implementing a long running IHostedService.

As shown in the code below, since MyService is a scoped service, we first need to create a scope because there will be no scope created for a hosted service by default.

public class MyProcessor : BackgroundService

{

private readonly IServiceProvider _services;

private readonly IList<Task> _processorWorkTasks;

public Processor(IServiceProvider services)

{

_services = services;

_processorWorkTasks = new List<Task>();

}

protected override async Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken cToken)

{

int numberOfProcessors = 100;

for (var i = 0; i < numberOfProcessors; i++)

{

await using var scope = _services.CreateAsyncScope();

var myService = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<IMyService>();

var workTask = myService.RunAsync(cToken);

_processorWorkTasks.Add(workTask);

}

await Task.WhenAll(_processorWorkTasks);

}

}

As shown above, we are calling myService.RunAsync, an async method, without await it. Hence, ExecuteAsync continues running without waiting for myService.RunAsync to complete. In other words, we will be treating the async method myService.RunAsync as a fire-and-forget operation. This can make it seem like the loop is executing tasks in parallel.

After the loop, we will be using Task.WhenAll to await all those tasks, allowing us to take advantage of concurrency while still waiting for all tasks to complete.

Problem

The code above will bring us an error as below.

System.ObjectDisposedException: Cannot access a disposed object.

Object name: ‘MySqlConnection’.

System.ObjectDisposedException: Cannot access a disposed context instance. A common cause of this error is disposing a context instance that was resolved from dependency injection and then later trying to use the same context instance elsewhere in your application. This may occur if you are calling ‘Dispose’ on the context instance, or wrapping it in a using statement. If you are using dependency injection, you should let the dependency injection container take care of disposing context instances.

If you are using AddDbContextPool instead of AddDbContext, the following error will occur also.

System.InvalidOperationException: A second operation was started on this context instance before a previous operation completed. This is usually caused by different threads concurrently using the same instance of DbContext. For more information on how to avoid threading issues with DbContext, see https://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?linkid=2097913.

The error is caused by the fact that, as we discussed earlier, EF Core does not support multiple parallel operations being run on the same DbContext instance. Hence, we need to solve the problem by having multiple DbContexts.

Solution 1: Scoped Service

This is a solution suggested by my teammate, Yimin. This approach is focusing on changing the background service, MyProcessor.

Since DbContext is registered as a scoped service, within the lifecycle of a web request, the DbContext instance is unique to that request. However, in background tasks, there is no “web request” scope, so we need to create our own scope to obtain a fresh DbContext instance.

Since our BackgroundService implementation above already has access to IServiceProvider, which is used to create scopes and resolve services, we can change it as follows to create multiple DbContexts.

public class MyProcessor : BackgroundService

{

private readonly IServiceProvider _services;

private readonly IList<Task> _processorWorkTasks;

public Processor(

IServiceProvider services)

{

_services = services;

_processorWorkTasks = new List<Task>();

}

protected override async Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken cToken)

{

int numberOfProcessors = 100;

for (var i = 0; i < numberOfProcessors; i++)

{

_processorWorkTasks.Add(

PerformDatabaseOperationAsync(cToken));

}

await Task.WhenAll(_processorWorkTasks);

}

private async Task PerformDatabaseOperationAsync(CancellationToken cToken)

{

using var scope = _services.CreateScope();

var myService = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<IMyService>();

await myService.RunAsync(cToken);

}

}

Another important change is to await for the myService.RunAsync method. If we do not await it, we risk leaving the task incomplete. This could lead to problem that DbContext does not get disposed properly.

In addition, if we do not await the action, we will also end up with multiple threads trying to use the same DbContext instance concurrently, which could result in exceptions like the one we discussed earlier.

Solution 2: DbContextFactory

I have proposed to my teammate another solution which can easily create multiple DbContexts as well. My approach is to update the MyService instead of the background service.

Instead of injecting DbContext to our services, we can inject DbContextFactory and then use it to create multiple DbContexts that allow us to execute queries in parallel.

Hence, the service MyService can be updated to be as follows.

public class MyService : IMyService

{

private readonly IDbContextFactory<MyDbContext> _contextFactory;

public MyService(IDbContextFactory<MyDbContext> contextFactory)

{

_contextFactory = contextFactory;

}

public async Task RunAsync()

{

using (var context = _contextFactory.CreateDbContext())

{

var result = await context.MyTable

.Where(...)

.ToListAsync();

...

}

}

}

This also means that we need to update AddDbContext to AddDbContextFactory in Program.cs so that we can register this factory as follows.

builder.Services.AddDbContextFactory<MyDbContext>(options =>

options.UseMySql(connectionString));

Using AddDbContextFactory is a recommended approach when working with DbContext in scenarios like background tasks, where we need multiple, short-lived instances of DbContext that can be used concurrently in a safe manner.

Since each DbContext instance created by the factory is independent, we avoid the concurrency issues associated with using a single DbContext instance across multiple threads. The implementation above also reduces the risk of resource leaks and other lifecycle issues.

Wrap-Up

In this article, we have seen two different approaches to handle concurrency effectively in EF Core by ensuring that each database operation uses a separate DbContext instance. This prevents threading issues, such as the InvalidOperationException related to multiple operations being started on the same DbContext.

The first solution where we create a new scope with CreateAsyncScope is a bit more complicated but If we prefer to manage multiple scoped services, the CreateAsyncScope approach is appropriate. However, If we are looking for a simple method for managing isolated DbContext instances, AddDbContextFactory is a better choice.

References

KOSD, or Kopi-O Siew Dai, is a type of Singapore coffee that I enjoy. It is basically a cup of coffee with a little bit of sugar. This series is meant to blog about technical knowledge that I gained while having a small cup of Kopi-O Siew Dai.