Let’s start with a problem that many of us in the systems engineering world have faced. You have a computationally intensive application such as a financial model, a scientific process, or in my case, a Discrete Event Simulation (DES). The code is correct, but it is slow.

In some DES problems, to get a statistically reliable answer, you cannot just run it once. You need to run it 5,000 times with different inputs, which is a massive parameter sweep combined with a Monte Carlo experiment to average out the randomness.

If you run this on your developer machine, it will finish in 2026. If you rent a single massive VM on cloud, you are burning money while one CPU core works and the others idle.

This is a brute-force computation problem. How do you solve it without rewriting your entire app? You build a simulation lab on Kubernetes. Here is the blueprint.

About Time

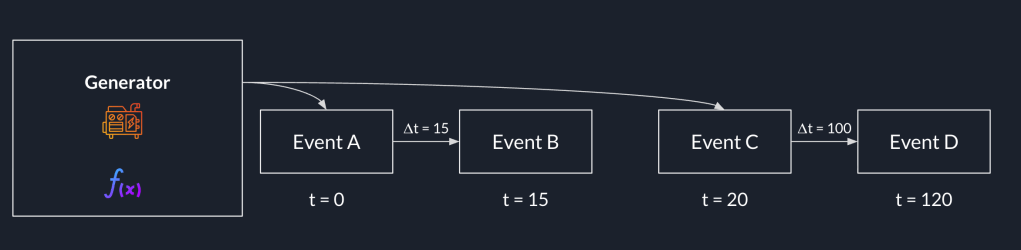

My specific app is a DES built with a C# library called SNA. In DES, the integrity of the entire system depends on a single, unified virtual clock and a centralised Future Event List (FEL). The core promise of the simulation engine is to process events one by one, in strict chronological order.

This creates an architectural barrier. You cannot simply chop a single simulation into pieces and run them on different pods on Kubernetes. Each pod has its own system clock, and network latency would destroy the causal chain of events. A single simulation run is, by its nature, an inherently single-threaded process.

We cannot parallelise the simulation, but we can parallelise the experiment.

This is what is known as an Embarrassingly Parallel problem. Since the multiple simulation runs do not need to talk to each other, we do not need a complex distributed system. We need an army of independent workers.

The Blueprint: The Simulation Lab

To solve this, I moved away from the idea of a “server” and toward the idea of a “lab”.

Our architecture has three components:

- The Engine: A containerised .NET app that can run one full simulation and write its results as structured logs;

- The Orchestrator: A system to manage the parameter sweep, scheduling thousands of simulation pods and ensuring they all run with unique inputs;

- The Observatory: A centralised place to collect and analyse the structured results from the entire army of pods.

The Engine: Headless .NET

The foundation is a .NET console programme.

We use System.CommandLine to create a strict contract between the container and the orchestrator. We expose key variables of the simulation as CLI arguments, for example, arrival rates, resource counts, service times.

using System.CommandLine;

var rootCommand = new RootCommand

{

Description = "Discrete Event Simulation Demo CLI\n\n" +

"Use 'demo <subcommand> --help' to view options for a specific demo.\n\n" +

"Examples:\n" +

" dotnet DemoApp.dll demo simple-generator\n" +

" dotnet DemoApp.dll demo mmck --servers 3 --capacity 10 --arrival-secs 2.5"

};

// Show help when run with no arguments

if (args.Length == 0)

{

Console.WriteLine("No command provided. Showing help:\n");

rootCommand.Invoke("-h"); // Show help

return 1;

}

// ---- Demo: simple-server ----

var meanArrivalSecondsOption = new Option<double>(

name: "--arrival-secs",

description: "Mean arrival time in seconds.",

getDefaultValue: () => 5.0

);

var simpleServerCommand = new Command("simple-server", "Run the SimpleServerAndGenerator demo");

simpleServerCommand.AddOption(meanArrivalSecondsOption);

simpleServerCommand.SetHandler((double meanArrivalSeconds) =>

{

Console.WriteLine($"====== Running SimpleServerAndGenerator (Mean Arrival (Unit: second)={meanArrivalSeconds}) ======");

SimpleServerAndGenerator.RunDemo(loggerFactory, meanArrivalSeconds);

}, meanArrivalSecondsOption);

var demoCommand = new Command("demo", "Run a simulation demo");

demoCommand.AddCommand(simpleServerCommand);

rootCommand.AddCommand(demoCommand);

return await rootCommand.InvokeAsync(args);

This console programme is then packaged into a Docker container. That’s it. The engine is complete.

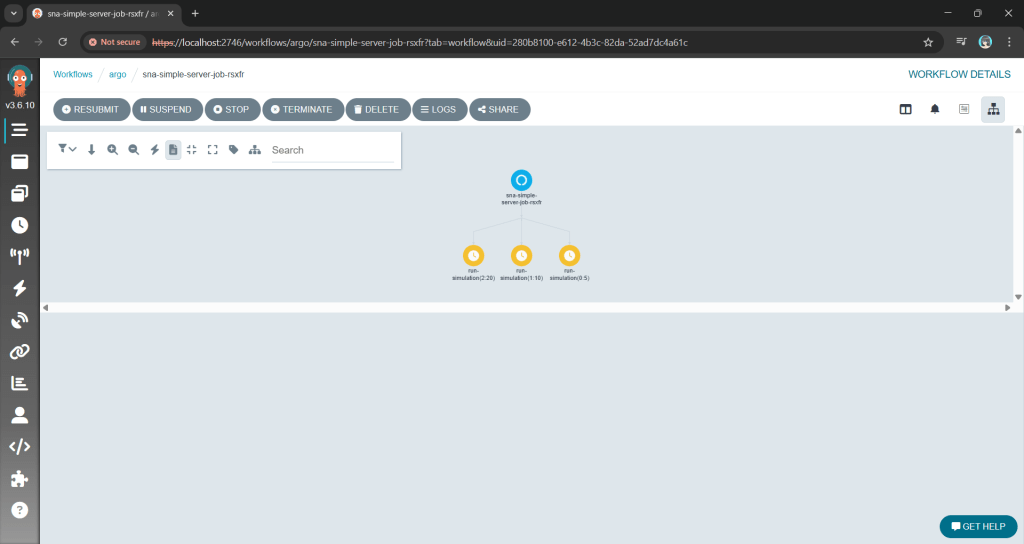

The Orchestrator: Unleashing an Army with Argo Workflows

How do you manage a great number of pods without losing your mind?

My first attempt was using standard Kubernetes Jobs. Kubernetes Jobs are primitive, so they are hard to visualise, and managing retries or dependencies requires writing a lot of fragile bash scripts.

The solution is Argo Workflows.

Argo allows us to define the entire parameter sweep as a single workflow object. The killer feature here is the withItems. Alternative, using withParam loop, we can feed Argo a JSON list of parameter combinations, and it handles the rest: Fan-out, throttling, concurrency control, and retries.

apiVersion: argoproj.io/v1alpha1

kind: Workflow

metadata:

generateName: sna-simple-server-job-

spec:

entrypoint: sna-demo

serviceAccountName: argo-workflow

templates:

- name: sna-demo

steps:

- - name: run-simulation

template: simulation-job

arguments:

parameters:

- name: arrival-secs

value: "{{item}}"

withItems: ["5", "10", "20"]

- name: simulation-job

inputs:

parameters:

- name: arrival-secs

container:

image: chunlindocker/sna-demo:latest

command: ["dotnet", "SimNextgenApp.Demo.dll"]

args: ["demo", "simple-server", "--arrival-secs", "{{inputs.parameters.arrival-secs}}"]

This YAML file is our lab manager. It can also be extended to support scheduling, retries, and parallelism, transforming a complex manual task into a single declarative manifest.

Instead of managing pods, we are now managing a definition of an experiment.

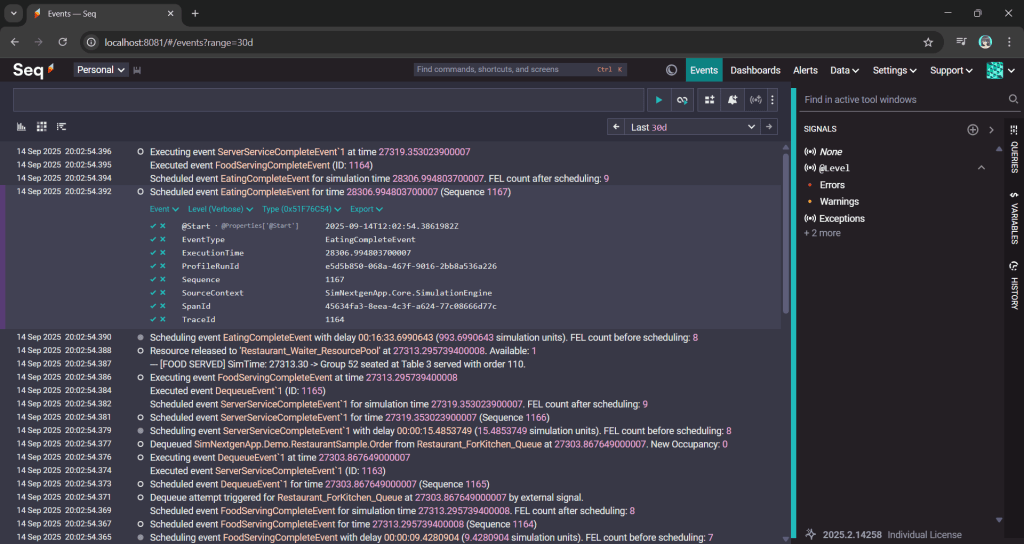

The Observatory: Finding the Needle in a Thousand Haystacks

With a thousand pods running simultaneously, kubectl logs is useless. You are generating gigabytes of text per minute. If one simulation produces an anomaly, finding it in a text stream is impossible.

We solve this with Structured Logging.

By using Serilog, our .NET Engine does not just write text. Instead, it emits machine-readable events with key-value pairs for our parameters and results. Every log entry contains the input parameters (for example, { "WorkerCount": 5, "ServiceTime": 10 }) attached to the result.

These structured logs are sent directly to a centralised platform like Seq. Now, instead of a thousand messy log streams, we have a single, queryable database of our entire experiment results.

Wrap-Up: A Reusable Pattern

This architecture allows us to treat the Kubernetes not just as a place to host websites, but as a massive, on-demand supercomputer.

By separating the Engine from the Orchestrator and the Observatory, we have taken a problem that was too slow for a single machine and solved it using the native strengths of the Kubernetes. We did not need to rewrite the core C# logic. Instead, we just needed to wrap it in a clean interface and unleash a container army to do the work.

The full source code for the SNA library and the Argo workflow examples can be found on GitHub: https://github.com/gcl-team/SNA

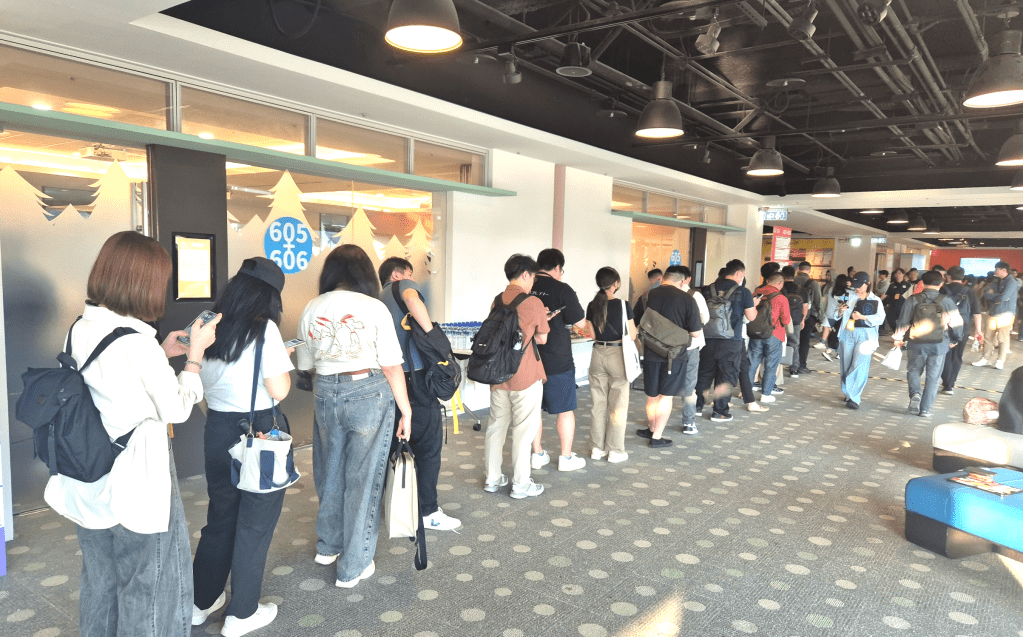

P.S. I presented an early version of this blueprint at the Hello World Developer Conference 2025 in Taipei. The discussions with other engineers there were invaluable in refining these ideas.